Classical Records of the Dorian & Danaan Israelite-Greeks

© William R. Finck Jr. 2007

© William R. Finck Jr. 2007

The Corinthians were Dorian Greeks. The Dorians were a tribe said to have invaded Greece, by all ancient accounts, a short time after the Trojan wars. The Greeks who inhabited all of the Peloponnese before the Dorian invasion, as well as areas of the mainland, were called everywhere “Danaans” (Danai) and “Achaians” by Homer. Modern historians assert that the Dorians came “from the north”, and point to the Dorian Tetrapolis, four cities (Erineus, Boeum, Pindus and Cytinium, for which see Strabo 9.4.10) which lie west of Phocis and north of Delphi on the Greek mainland, as evidence of this. These historians also claim that all Aryans came “from the north” into the ancient world at one time or another, yet they are consistently in error. Homer is given much credit by Strabo for his knowledge and accuracy in describing the peoples of the οἰκουμένη and the regions where they lived, and the poet is constantly cited by the geographer. Homer described all of the people of Greece, and the peoples and places known to the Greeks in the period which he wrote about. Yet Homer makes no mention of the cities of the Tetrapolis, of Dorians in Greece, or anywhere in the north. The Dorians, who invaded Greece by sea (hardly necessary if they came from the north) and pushed the Danaans out of the Peloponnese, and who also later founded their mainland cities, are only mentioned by Homer as being on Crete (in his Odyssey, Book 19).

From Alexander Pope's Odyssey, Book 19:

From Alexander Pope's Odyssey, Book 19:

"Crete awes the circling waves, a fruitful soil!

And ninety cities crown the sea-born isle:

Mix'd with her genuine sons, adopted names

In various tongues avow their various claims:

Cydonians, dreadful with the bended yew,

And bold Pelasgi boast a native's due:

The Dorians, plumed amid the files of war,

Her foodful glebe with fierce Achaians share;

Cnossus, her capital of high command;

Where sceptred Minos with impartial hand

Divided right: each ninth revolving year,

By Jove received in council to confer.

It is my contention that the Dorians actually came from Dor in Palestine, a city on the coast of the land of Manasseh, and where many ancient “Greek” artifacts have been found by archaeologists, for which see Biblical Archaeology Review, July-August 2001, p. 17, and November-December, 2002, “Gorgon Excavated At Dor”, p. 50. These artifacts show a “Greek” presence at Dor as early as the seventh century B.C., and are certainly much earlier than the Hellenistic period. The seventh century B.C. is the time of the last recorded Assyrian activity in Israel (see Ezra 4:2, Esar-Haddon reigned from 681 B.C.), and the last deportations of Israelites which happened about 676 B.C. (see The Assyrian Invasions And Deportations of Israel by J. Llewellyn Thomas). For evidence that Israelite priests were indeed present at Dor see Biblical Archaeology Review, May-June 2001, p. 21 and the article there. If the Dorians migrated from Palestine, rather than from the north, Crete is a logical place to begin settling, enroute to the west. Further evidence that the Dorians were Israelites is found in Josephus, in his record of a letter written by a Spartan (or Lacedemonian, and they were also Dorian Greeks) king to Jerusalem about 160 B.C., which is found in Antiquities 12.4.10 (12:226-227):

“Areus, King of the Lacedemonians, To Onias, Sendeth Greeting. We have met with a certain writing, whereby we have discovered that both the Judaeans and the Lacedemonians are of one stock, and are derived from the kindred of Abraham. It is but just, therefore, that you, who are our brethren, should send to us about any of your concern as you please. We will also do the same thing, and esteem your concerns as our own, and will look upon our concerns as in common with yours. Demotoles, who brings you this letter, will bring your answer back to us. This letter is foursquare; and the seal is an eagle, with a dragon in his claws.” That this account of the letter, and its contents, is factual is verified by the reply to it recorded by Josephus at Antiq. 13.5.8 (13:163-170), by Jonathan the high priest.

The reply to this letter was long delayed, due to the Maccabean wars and problems amongst the Judaeans which are described by Josephus. Since it is also documented in 1st Maccabees chapter 12 in the Apocrypha, here the version from Brenton’s Septuagint is supplied: “Jonathan the high priest, and the elders of the nation, and the priests, and the other people of the Judaeans, unto the Lacedemonians their brethren send greeting: There were letters sent in times past unto Onias the high priest from Darius, who reigned then among you, to signify that ye are our brethren, as the copy here underwritten doth specify. At which time Onias entreated the ambassador that was sent honourably, and received the letters, wherein declaration was made of the league and friendship. Therefore we also, albeit we need none of these things, for that we have the holy books of scripture in our hands to comfort us, have nevertheless attempted to send unto you for the renewing of brotherhood and friendship, lest we should become strangers unto you altogether: for there is a long time passed since ye sent unto us. We therefore at all times without ceasing, both in our feasts, and other convenient days, do remember you in the sacrifices which we offer, and in our prayers, as reason is, and as it becometh us to think upon our brethren: and we are right glad of your honor. As for ourselves, we have had great troubles and wars on every side, forsomuch as the kings that are round about us have fought against us.  Howbeit we would not be troublesome unto you, nor to others of our confederates and friends, in these wars: for we have help from heaven that succoureth us, so as we are delivered from our enemies, and our enemies are brought under foot. For this cause we chose Numenius the son of Antiochus, and Antipater the son of Jason, and sent them unto the Romans, to renew the amity that we had with them, and the former league. We commanded them also to go unto you, and to salute you, and to deliver you our letters concerning the renewing of our brotherhood. Wherefore now ye shall do well to give us an answer thereto. And this is the copy of the letters which Oniares sent. Areus king of the Lacedemonians to Onias the high priest, greeting: It is found in writing, that the Lacedemonians and Judaeans are brethren, and that they are of the stock of Abraham: now therefore, since this is come to our knowledge, ye shall do well to write unto us of your prosperity. We do write back again to you, that your cattle and goods are our’s, and our’s are your’s. We do command therefore our ambassadors to make report unto you on this wise.” (1st Maccabees 12:6-23)

Howbeit we would not be troublesome unto you, nor to others of our confederates and friends, in these wars: for we have help from heaven that succoureth us, so as we are delivered from our enemies, and our enemies are brought under foot. For this cause we chose Numenius the son of Antiochus, and Antipater the son of Jason, and sent them unto the Romans, to renew the amity that we had with them, and the former league. We commanded them also to go unto you, and to salute you, and to deliver you our letters concerning the renewing of our brotherhood. Wherefore now ye shall do well to give us an answer thereto. And this is the copy of the letters which Oniares sent. Areus king of the Lacedemonians to Onias the high priest, greeting: It is found in writing, that the Lacedemonians and Judaeans are brethren, and that they are of the stock of Abraham: now therefore, since this is come to our knowledge, ye shall do well to write unto us of your prosperity. We do write back again to you, that your cattle and goods are our’s, and our’s are your’s. We do command therefore our ambassadors to make report unto you on this wise.” (1st Maccabees 12:6-23)

Now many may object to identifying the later Corinthians of Paul’s time as Dorians, because the city was destroyed and later rebuilt by the Romans. And this is true, for in 146 B.C. the Roman consul Leucius Mummius captured Corinth and razed it by fire, selling the surviving populace into slavery, as was customary for the Romans to do. Giving the account, Strabo tells us that afterwards “the Sicyonians obtained most of the Corinthian country” (8.6.23). That the Sicyonians, those of the neighboring district, were also Dorians is evident in many places besides Diodorus Siculus at 7.9.1 (“Fragments of Book VII” in the Loeb Library edition) where he states: “it remains for us to speak of Corinth and of Sicyon, and of the manner in which the territories of these cities were settled by the Dorians.” Sicyon, a sort of sister city of Corinth, was its equal in the arts, where Strabo says of Corinth: “for both here and in Sicyon the arts of painting and modelling and all such arts of the craftsman flourished most” (8.6.23). So in this manner did the territory of Corinth retain a Dorian composition of its population, but that is not the entire story.

Strabo speaks of the rebuilding of Corinth as such was ordered by Caesar, which began about 44 B.C., and states that “it was restored again, because of its favorable position, by the deified Caesar, who colonised it with people that belonged for the most part to the freedmen class” (8.6.23). Yet Diodorus Siculus (in “Fragments of Book XXXII” in the Loeb Library edition) is recorded as telling us further: “Gaius Iulius Caesar (who for his great deeds was entitled divus), when he inspected the site of Corinth, was so moved by compassion and the thirst for fame that he set about restoring it with great energy. It is therefore just that this man and his high standard of conduct should receive our full approval and that we should by our history accord him enduring praise for his generosity. For whereas his forefathers had harshly used the city, he by his clemency made amends for their unrelenting severity, preferring to forgive rather than to punish” (32.27.3).

Now the only way that Caesar’s deeds could justly be called a restoring, clemency, or forgiveness, as they are here, would be that the “freedmen” which he let repopulate the rebuilt Corinth were descendants of those Corinthians enslaved in its destruction 102 years earlier. This is in keeping with Roman custom, as is evident at Acts 6:9, where we see Judaean “freedmen” living in the homeland of their ancestors, whom must have been taken captive in the Roman conquest of Judaea by Pompey some generations earlier. The settling of anyone but Dorians in a rebuilt Corinth could not have been termed clemency or forgiveness, but rather would have been seen as an insult to the Sicyonians, the Lacedemonians, and the rest of the Dorians of the Peloponnese. Yet an examination of the Roman custom along with Diodorus’ words surely implies that when Strabo attests that the restored Corinthians were “for the most part” of the “freedmen class”, he surely meant those freedmen descended from the original Corinthian stock taken captive.

Furthermore, Paul at 1 Corinthians 10:1 tells the Corinthians “Now I do not wish you to be ignorant, brethren, that our fathers were all under the cloud, and all had passed through the sea”, therefore telling the Corinthians that their ancestors had been in the Israelite Exodus out of Egypt.

The Greeks of Thebes were identified as Phoenicians, and the Greek ‘gods’ Heracles (Hesiod’s Theogony, 530) and Dionysus (Diodorus Siculus, 1.23.2-8; 3.64.3 and 3.66.3) were both said to be born there. Cadmus the Phoenician was said to have founded Thebes, and also to have been the grandfather of Dionysus (Diodorus Siculus 4.2.1, 4.2.2-3 et al.), and to have come from the city of Thebes in Egypt (1.23.4). These Phoenicians of Thebes were often associated with the Danaans. Euripides’ Phoenician Women, a 5th century play, was written about the women of Thebes and events said to have taken place long before the Trojan War, which Aeschylus also wrote about in Seven Against Thebes, the succession battle between the sons of Oedipus for the throne of Thebes, in which Polynices enlists the help of the Danaans against his brother Eteocles.

The Greeks of Thebes were identified as Phoenicians, and the Greek ‘gods’ Heracles (Hesiod’s Theogony, 530) and Dionysus (Diodorus Siculus, 1.23.2-8; 3.64.3 and 3.66.3) were both said to be born there. Cadmus the Phoenician was said to have founded Thebes, and also to have been the grandfather of Dionysus (Diodorus Siculus 4.2.1, 4.2.2-3 et al.), and to have come from the city of Thebes in Egypt (1.23.4). These Phoenicians of Thebes were often associated with the Danaans. Euripides’ Phoenician Women, a 5th century play, was written about the women of Thebes and events said to have taken place long before the Trojan War, which Aeschylus also wrote about in Seven Against Thebes, the succession battle between the sons of Oedipus for the throne of Thebes, in which Polynices enlists the help of the Danaans against his brother Eteocles.

Diodorus Siculus, quoting from the earlier historian Hecataeus of Abdera, who gave a strange account of the Israelite Exodus from Egypt from an Egyptian viewpoint, says “the aliens were driven from the country, and the most outstanding and active among them banded together and, as some say, were cast ashore in Greece and certain other regions; their leaders were notable men, chief among them being Danaus and Cadmus. But the greater number were driven into what is now called Judaea ... The colony was headed by a man called Moses, outstanding both for his wisdom and for his courage.”

Cadmus, called “the Phoenician” throughout Classical Greek literature, was the legendary founder of Thebes. Danaus, “the Egyptian” as he also is usually called, was the legendary leader of the Danaans (Danai) who came to Greece from Egypt, who could only have been a portion of the Israelite tribe of Dan (cf. Judges 5:17, Ezek. 27:19). This event was parodied in later Classical literature as the flight of the “daughters of Danaus” from the “sons of Aegyptus”, an example being the play by Aeschylus, Suppliant Maidens. The point here is to show that the Danaans came to Greece directly from Egypt, and so were never “under the cloud” in the Exodus, having left Egypt in a different manner.

The Romans descended from the Trojans (for which see Strabo 5.3.2, 13.1.27 et al., Diodorus Siculus 7.4.1-4, 7.5, Virgil’s Aeneid and many other sources), and neither could their fathers have been “under the cloud” because Darda, the son of Mahol of the tribe of Judah-Zerah (1 Kings 4:31; 1 Chron. 2:6) by all accounts must have lived long before the Exodus. Darda was the legendary founder of Troy, and Homer consistently refers to the Trojans as Dardans. Chalcol (1 Kings 4:31, or Calcol at 1 Chron. 2:6) must be the Calchas of Greek legend who founded Pamphylia (i.e. Herodotus 7.91, Strabo 14.4.3), called Chalcad in the Septuagint in Kings, but Kalchal in Chronicles. The names of these Greek legends being found in the Bible belonging to Israelites, compared to Solomon in wisdom and who therefore must have been great men, are surely beyond coincidence. Zerah went to Egypt without his famous sons, who are not mentioned elsewhere in the Biblical accounts (Gen. 46:12), and Troy was so called in Hittite records which existed two centuries before the Exodus. So then, the Zerah-Judah Trojans, ancestors of the Romans, must have parted from the Israelites long before that time, possibly even before Jacob went to Egypt.

The Romans descended from the Trojans (for which see Strabo 5.3.2, 13.1.27 et al., Diodorus Siculus 7.4.1-4, 7.5, Virgil’s Aeneid and many other sources), and neither could their fathers have been “under the cloud” because Darda, the son of Mahol of the tribe of Judah-Zerah (1 Kings 4:31; 1 Chron. 2:6) by all accounts must have lived long before the Exodus. Darda was the legendary founder of Troy, and Homer consistently refers to the Trojans as Dardans. Chalcol (1 Kings 4:31, or Calcol at 1 Chron. 2:6) must be the Calchas of Greek legend who founded Pamphylia (i.e. Herodotus 7.91, Strabo 14.4.3), called Chalcad in the Septuagint in Kings, but Kalchal in Chronicles. The names of these Greek legends being found in the Bible belonging to Israelites, compared to Solomon in wisdom and who therefore must have been great men, are surely beyond coincidence. Zerah went to Egypt without his famous sons, who are not mentioned elsewhere in the Biblical accounts (Gen. 46:12), and Troy was so called in Hittite records which existed two centuries before the Exodus. So then, the Zerah-Judah Trojans, ancestors of the Romans, must have parted from the Israelites long before that time, possibly even before Jacob went to Egypt.

Later “Phoenician” colonists in the Mediterranean were the Israelites of the northern tribes who sailed from Tyre and Sidon. These settled not in Greece nor in Italy, but in Cyprus, Cilicia, Miletus, Carthage, Iberia and other points further west. Among the other Greek tribes, the Pelasgians were in Greece before the Danaans, the Aeolians are but a division of the Danaans, and the Ionians are descendants of Japheth. There are no other candidate tribes but the Dorians in Italy or Greece who could have been “under the cloud”, as Paul states of the Corinthians’ ancestors at 1 Cor. 10:1. Paul must have been addressing, at least for the most part, Dorian Greeks.

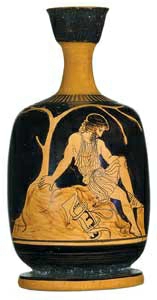

One outstanding feature of Paul’s letters to the Corinthians are his frequent admonishments to them not to commit fornication (πορνεία, illicit sex including, but not limited to, prostitution and race-mixing), which are found at 1 Cor. 5, 6, 7, 10, and 2 Cor. 12. The Corinthians of old were famous for their fornicating, to the extent that a verb was coined, κορινθιάζομαι (korinthiazomai), which meant to practise fornication, as used by Aristophanes and others. The city was also famous for its temple of Aphrodite and the courtesans, slaves which worked as temple prostitutes (πόρναι), which belonged to the temple.

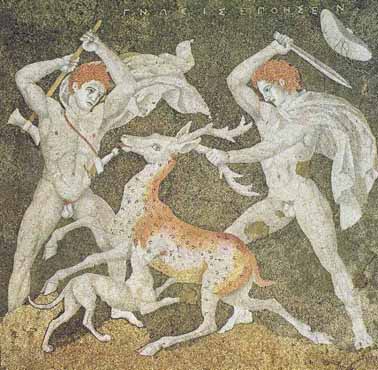

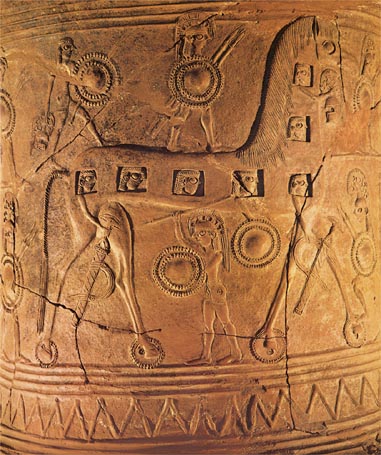

White Persians and Greeks:

A scientific restoration of the original color in ancient Geek sculpture. Above we have a battle scene between Persians and Greeks. Click the picture for the original catalog from the Harvard art museum, or here for a link to a copy of the original article. The Persians here are exactly as the ancient historian Xenophon described them in his Hellenica; click here for the PDF image of the appropriate page from the Harvard Loeb Library edition. Below is another image, of a Greek archer, from the same resource.

The image below is a portrait of Alexander the Great.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.