The True Story of Haym Salomon

The True Story of Haym Salomon: Revolutionary Money Lender

by JOHN TIFFANY

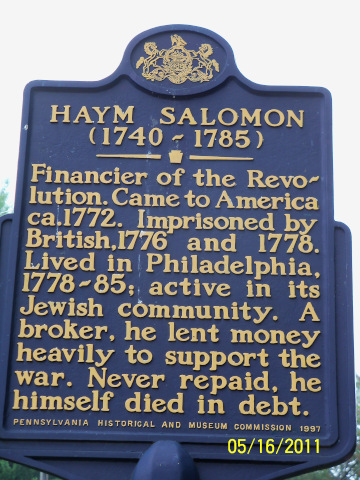

Although little known in most circles,1Haym Salomon is frequently promoted as a famous Jewish American patriot. Known in propaganda as "the financier of the American Revolution," he is said to have been twice arrested for his activities in connection with the Sons of Liberty and was imprisoned by the British. It is claimed that he helped American and French prisoners escape and encouraged British soldiers to desert to the American forces. In 1778, about to be arrested as a spy, the New Yorker escaped to Philadelphia. But what were the real achievements of the “patriot broker of the revolution”? Have they been exaggerated?

Odd as it might seem, it was a group of Jewish citizens who investigated and exploded the Haym Salomon myth. A Jewish congressman named Emanuel Celler of New York called upon some patriotic Jews named Max Kohler and a Mr. Oppenheim. Presented here, in condensed form, is what they learnt. The Kohler Report is exceedingly difficult to find even in the best-stocked libraries, although there is a copy in the Library of Congress. Despite the report, there is a persistent and noisy effort to persuade the American people that Haym Salomon was "the financier of the revolution," and that the services of this man to the patriot cause were unique. As a result of the propaganda on his behalf, the average American, if he has heard of Salomon, thinks he was the savior of the revolution.

Owing to the fact that most Jews in America in the colonial era were merchants and tradesmen, they were among the first in this country to feel the disastrous effects of British repressive measures. The continuation and enforcement of British laws against America would have destroyed the economic prospects of most of the Jewish people in America. For example, the British laws which required Americans to trade only with the British West Indies threatened to destroy the profitable trade which Jewish merchants had developed with the French, Spanish and Dutch West Indies. Additionally, the royal proclamation of 1763 forbidding settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains stuck a heavy blow against the prospects of Jewish traders and land speculators. Not surprisingly, then, the majority of American Jews threw in their lot with the revolutionary colonists early on in the independence movement.

The enforcement of the non-importation agreements was mostly in the hands of the Sons of Liberty, an organization formed by Samuel Adams and others in the latter part of 1765. This group was composed largely of mechanics, artisans and day laborers and served as the spearhead of the movement to free the American colonies from England. Relying on direct action rather than on petitions to a hostile Parliament, the Sons of Liberty pushed forward the revolutionary movement by prodding those members of the mercantile, landed and professional "aristocracy" who wanted to advance slowly, if at all, in the direction of freedom for Americans.

The Sons attracted the support of a number of Jews, most notable of whom was Haym Salomon. Salomon was born in Poland in 1740, of Portuguese Jewish ancestry. At the age of 30 he became an ardent advocate of Polish independence and a close friend of Count Thadeusz Kosciusko and Count Casimir Pulaski, who were to become supporters of the American Revolution.

George Washington relied greatly on “the [real] financier of the Revolution,” Robert Morris. Morris, from Pennsylvania, was one of the 40 or 50 delegates to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia that dealt with the July 4, 1776 Declaration of Independence. Morris later helped to ratify the Constitution and went on to participate in the First Congress under the Constitution. Throughout his public life, Morris, the wealthiest merchant in the state, with aristocratic aspirations, was charged by critics with furthering his private interests.

Salomon was born in Lissa, Poland in 1740, and had apparently traveled considerably after leaving Poland at some unascertained date. He apparently arrived in America in 1772. Salomon was married in January 1777 in New York to Rachel Franks, daughter of Moses B. Franks of New York, who belonged to a distinguished American family, which included Jacob Franks of New York, who had been commissary to the British government during the French and Indian War and had handled hundred of thousands of dollars or pounds worth of property.

Salomon arrived in Philadelphia about August 25, 1778, practically penniless, after getting away from British soldiers in New York, who had imprisoned him on suspicion of arson. The British seized his entire fortune, which he stated to have been between 5,000 and 6,000 pounds sterling. There is no known evidence of that money ever having been refunded to him or his family. Some sources say that he "escaped," but according to the book War! War! War! by “Cincinnatus,” he was actually released at the request of the British government. It seems they had entered into an agreement with him to use his language skills to communicate with their German (Hessian) troops. Instead, Salomon then made his way to Philadelphia.

There is a myth that Salomon loaned large sums of money to the new American government. However, a "Letter Book" containing copies of letters written by or on behalf of Salomon between July 1781 and July 1783, which had belonged to Salomon himself, shows that as late as 1782, he was able for the first time to spare money to aid his indigent parents in Poland by sending them funds, and he protested on July 10, 1783, that his means did not permit him to take care of a nephew, who his Polish relatives were sending to America to him without his authorization. He wrote: ''Your ideas of my riches are too extreme. Rich I am not, but the little I have, I think it my duty to share with my poor father and mother." These letters alone dispose of the theory that Salomon had any considerable fortune to lend the government, even if he had wished to do so.

Had Salomon been in possession of the sums he is credited by his descendants with having lent our government, he would have been one of the richest men in America. Salomon's financial connection with the government began only a few months before the Battle of Yorktown on October 19, 1781 ended the war, and years after Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga. While we were in sore financial straits in 1781, the war would nevertheless have been won by us had Salomon never lived, and the effort of Russell and others to depict Salomon as practically the savior of our country is absurd, although he was, no doubt, Morris's chief assistant.

An able Virginia historian named Eckenrode, in reviewing the Russell book in The New York Evening Sun on October 31,1930, remarks: “If Salomon had never lived, the American cause would have triumphed. It was not from a single broker, no matter how patriotic, that the means were obtained to carry the war to a successful conclusion but from France and Holland.”

With his many connections, innate financial genius and a remarkable grasp of foreign languages, acquired on his travels, Salomon was able to float about $200,000 worth of securities for Robert Morris during 1781-82, Morris having been superintendent of finance of the fledgling U.S. government. In July 1782 Morris authorized Salomon to call himself “broker to the Office of Finance” of the United States, as Morris's diary shows.

Oppenheim discovered, from the bank records, of which he had made photographic copies, that Salomon's way of dealing with the government was to secure U.S. government paper to negotiate by sale thereof. He would “receipt” for the same. As he disposed of the same--quite uniformly at an enormous discount--he would draw his own checks in payment. Haym M. Salomon (Haym Salomon's son) or the latter's agents persuaded several committees of Congress that these checks--proceeds of the sale of government paper--somehow represented "loans" by him to the government from his own funds. This result was accomplished, evidently, by concealing the course of dealings referred to, showing that he first received government paper to sell for it, and by concealing the size of his own fortune.

The scheme was further manipulated by a device allowing Haym M. Salomon to introduce what lawyers call inferior "secondary evidence" of the alleged loans, namely, evidence that the original government notes or other proofs of indebtedness to him had been lost. He evidently opened the door to the receipt of such evidence by the unsubstantiated, improbable claim that his original vouchers and papers had been lent to President Tyler for examination and had been lost while in that custody. However, no plausible reason suggests itself as to why the president should have wanted to examine these papers.

Maxwell House® Coffee Honors Famous Jewish-American Patriots

HAYM SALOMON 1740-1785

Financier • Banker of the American Revolution • Patriot

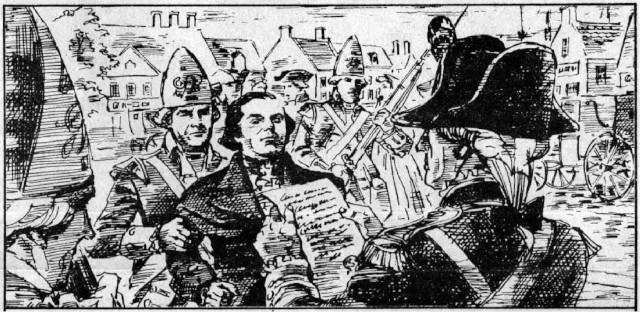

This cartoon. is one of a series called “Maxwell House Coffee Honors Famous Jewish-American Patriots,” and appeared in the B'nai B'ritli Messenger of March 7, 1975. Captioned simply "Haym Salomon, 1740-1785, Financier / Banker of the American Revolution / Patriot," it shows Salomon being arrested by the redcoats for his activities in the Sons of Liberty.

Stronger evidence having been demanded by Congress, it was secured as follows: The claim now was chiefly based on securities Salomon had owned at the time of his death, which were represented as issued in payment of "loans" he made the government. In fact, as above shown, he did not have the money to make such, or any other substantial loans. Next, these were current as “money” at the time, though largely depreciated, but some were “investments.” Their possession, even prima-facie, does not indicate that they represented original loans to the government. Moreover, Salomon was a dealer in these very securities, and bought and sold them daily, according to his own advertisements, so in his hands there was even less reason to suppose they represented advances in such sums, which he had made the government.

But Oppenheim went further and looked up the history of the securities involved, listed in detail in the “inventory” and “account” of Haym Salomon's administrators soon after his death. Oppenheim showed that nearly all these issues antedated Salomon's arrival in Philadelphia and his connection with the government.

Oppenheim had Photostats made of the original surrogate court records of Philadelphia, which showed that the proof submitted many years after Salomon's death by his son, Haym M., was false in that the bulk of the securities which he owned at the time of his death, on which the claim of loans to the government rested, were described in a document purporting to be officially certified in 1828 as ”liquidated currency,” whereas they were “unliquidated,” according to the original records, thereby increasing nearly all the amounts involved 40-fold.

Russell glosses over this serious incident in his book (291-92). He is emphatic that “it is clear that Haym M. Salomon never suspected” these discrepancies, even though there is not a particle of evidence as to how they occurred.

Perhaps the clerk in the Philadelphia public office made a mistake, when giving this “certified copy,” and the item $199,214.45, figuring in the congressional reports in alleged certified copies as “Continental liquidated dollars” instead of “unliquidated,” was so misdescribed. Perhaps it was made worthwhile for the clerk to falsely certify to the paper in this form, increasing the holding 40-fold, according to the prevailing law, under which "unliquidated dollars" were scaled down to one-40th of their face, in accordance with a measure of their depreciated value, making a holding of about $5,000 figure as $200,000 liquidated; this item constituted four-fifths of the whole estate. Or perhaps the certified transcript of the administrator's accounts was fraudulently altered, after execution but before submission to Congress, with or without Haym M. Salomon's knowledge. We cannot determine today who was responsible, but $200,000 out of the alleged holdings of $353,729.33 is thus reduced to $5,000. Oppenheim's next important finding is that the Philadelphia Surrogate Court records affirmatively attest from the Haym Salomon administrator's account that the bulk of the remaining securities was turned over by the administrators to his chief creditor, the Bank of North America, to be applied to the reduction of their claim, when sold. No doubt they turned them in to the government or otherwise disposed of them, and the government or the states, after such transfer, owed the money for which they were to be redeemed to that bank, and not to the Haym Salomon estate. So much for the enormous unpaid claim, which an “ungrateful country” has never acknowledged or paid. Russell glosses over the incident, after partially concealing it, with the admission (290) that there was no basis for any “legal claim” in favor of his estate, and “because these securities were delivered to the creditors, the heirs were left penniless.”

Thus it can be seen that the claims of those who would make Haym Salomon the "financial hero of the American Revolution" are completely groundless.

FOOTNOTES:

1 For example, there is no entry for Salomon in The Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, Mark M. Boatner III, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 1994.

2 "Cincinnatus," War! War! War! Sons of Liberty, Metairie, Louisiana, 1984.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Anonymous, The Story of the George Ww;hington, Robert Morris, Haym Salomon Monument, with the Proceedings at the Unveiling and Dedication, December 15th, 1941, the One Hundred Fiftieth Anniversary of the Ratification of the Bill of Rights, The Patriotic Foundation of Chicago, Chicago, 1942.

Cincinnatus, War! War! War!, 3rd ed., Sons of Liberty, Metairie, Louisiana, 1984.

Fast, Howard, Haym Salomon; Son of Liberty, J. Messner, Inc. New York, circa 1941.

Foner, Philip S., Jews in American History, 1654-1865, International Publishers, New York, 1945.

Knight, Vick, Send for Haym Salomon! Haym Salomon Foundation, in collaboration with Borden Pub. Co., Alhambra, Calif., cl976.

Kohler, Max, an open letter to Congressman Celler, dated 1931.

Peters, Madison Clinton, Haym Salomon: The Financier of the Revolution-An Unwritten Chapter in American History, Trow Press, New York, 1911.

Peters, Madison C., The Jews Who Stood by Washington: An Unwritten Chapter in American History, Trow Press, New York, 1915.

Russell, Charles Edward, Haym Salomon and the Revolution, Books for Libraries Press, Freeport, N.Y., 1970.

Schwartz, Laurens R., Jews and the American Revolution: Haym Salomon and Others, McFarland & Co., Jefferson, N.C., cl987.

The Jewish Tory Movement in the American Revolution . . .

Certain American Jews allied themselves with the patriots in the American Revolution, but others, especially some of the richer ones, fearing a movement that aimed to secure greater freedom for the common people, became Tories. David Franks, one of the Philadelphia merchants who had signed the original non-importation agreements, became a prominent Tory and was charged with giving secret aid to the enemy.

In July 1780, the state of Rhode Island passed an act of banishment against those who had "left this State and joined the enemies thereof." Included in this list was Isaac Hart, wealthy Jewish merchant of Newport, who was a Tory. In 1776, when New York fell into British hands, 15 Jews joined with others in signing a ''loyal address" to Sir William Howe and his brother, Lord Howe. Abraham Wagg, one of the 15, served in the British militia and in 1778 engaged in propaganda for the king by urging the Americans to end their alliance with France and agree to a negotiated peace with England.

SOURCE: Jews in American History, 1654-1865, Philip S. Foner, International Publishers, New York, 1945.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Recent comments