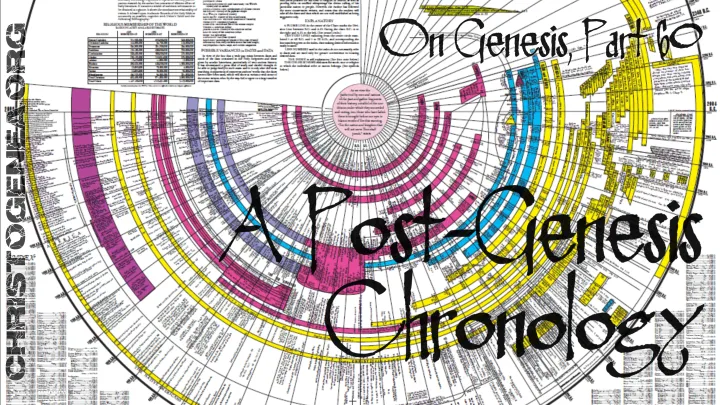

On Genesis, Part 60: A Post-Genesis Chronology

On Genesis, Part 60: A Post-Genesis Chronology

As we have often stated, one of the primary endeavors of this ministry is to provide Christian Identity with a firm academic foundation. That is because Christian Identity is Truth, and it certainly can be established in Scripture, history and archaeology that it is truth. Of course, our enemies can find ways to try to undermine us, just as they have found countless ways to criticize Scripture itself. But those ways are hardly honest, and always deceptive. One of the many avenues they have exploited in order to achieve their ends is Biblical chronology. They take simplistic interpretations of certain passages and use them to assert that somehow the Bible is false, that it can only be a collection of fairy tales, because, for example, there is no record in Egypt that the Israelites were in slavery there for four hundred years. But upon deep scrutiny of those same passages, and with an accurate understanding of Scripture and history, all of their attacks fail.

In recent weeks here we have concluded a commentary of the Book of Genesis, and in the course of that work we had provided a rather detailed chronology, using the Septuagint as our primary resource, which in this respect is certainly much more accurate than the translations which are based on the Masoretic Text, such as the popular King James Version. In that chronology, we asserted that among the last significant events in Genesis, Jacob had gone to Egypt with his family around 1665 BC, and since the call of Abraham was about 1880 BC, when the patriarch was 75 years old, and since Paul of Tarsus had written in Galatians chapter 3 that there were 430 years from the time of that call to the giving of the law at Sinai, the sojourn to Egypt was halfway through that period, leaving 215 years. So from the time Jacob went to Egypt, there would be another 215 years until the giving of the law at Sinai some time around 1450 BC. Moses, having been 80 years old at Sinai, must have been born some time around 1530 BC.

Therefore the beginning of the oppression of the children of Israel in Egypt must have been before 1530 BC, as Moses had been exposed as an infant according to the demands of the oppressing pharaoh. But it is apparent that at the death of Joseph around 1595 BC, Israel had not yet been oppressed by the Egyptians. However as we have also explained, in Egyptian history there is evidence that Canaanite tribes from the east, often called Hyksos, had come to occupy at least parts of Lower Egypt and the area of the Delta in which the Israelites were settled, a period which is usually dated by archaeologists to have begun some time around the time of Jacob’s death in 1648 BC. The Scripture is entirely silent on this period, but there is no indication in Scripture that the Hyksos had oppressed Israel up to the time of the death of Joseph. As we have also stated, this circumstance also seems to have disguised the presence of the Israelites in Egypt, since they were also viewed as Asiatics by the Egyptians.

So it is evident that once the Hyksos were driven from Lower Egypt, a future pharaoh, who “knew not Joseph”, would have naturally viewed the Asiatic Israelites no differently than the Asiatic Hyksos, who were apparently Canaanites. That explains why there is no distinction of Israel or Hebrews in the Egyptian records of the time, when the Egyptians had regained control of Lower Egypt. The last pharaoh of the 17th Dynasty, Kamose I, began the process of driving out the Hyksos before his death in 1550 BC, and his successor, the first pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, Ahmose I, completed the task soon after, some time around 1540 BC but perhaps a little later than that. When Moses was born Israel was oppressed under their new Egyptian rulers, and when he is saved from the water by some princess, she gives him her family name. That name is apparent in many figures from these dynasties, Ahmose, Kamose, and the subsequent line of kings many of whom bore the name Thutmose.

As a digression, in the past we have imagined that the princess who saved Moses from the water may very likely have been Hatshepsut, and while that seemed plausible, here with this much more precise understanding of the chronology of the period, that circumstance is not possible, as Hatshepsut was evidently not born until about 1507 BC, having been the daughter of Thutmose I, the grandson of Ahmose and the third pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty. In any event, the princess who saved Moses had given him his name because it was her own family name, so she had adopted him as her own child, and she was apparently confident that she could keep him in that manner. (This is an example of feminism in ancient Egypt, as she would burden her father and perhaps some current or future husband with his support.)

So evidently, Joseph may have retired from government when the pharaohs of the 13th Dynasty under whom he ruled had left Itjtawy in Lower Egypt and retreated to Thebes in the face of the invading Hyksos. But it is also possible that Joseph may have been retained as an administrator by the new Hyksos rulers, who had also fancied themselves as pharaohs. However it would only be conjecture to make a case for either possibility as if it were a fact. There is no direct evidence in Scripture for either assertion, Joseph’s retirement or his continuance in a Hyksos government. But the description of the balance of his life which is found in the final chapter of Genesis does support an assertion that Joseph had remained in Goshen throughout this time, where we read in Genesis chapter 50 (50:22-23) that his grandchildren “were brought up upon Joseph’s knees.”

On account of this general chronology of Jacob in Egypt, which is at least partially understood by some Christian academics, many of them wander into the error that the family of Jacob were the Hyksos in Egypt, and that it is they who had ruled all of Lower Egypt for as long as a hundred years until the time of Kamose I. However it is highly unlikely that Jacob, who is said to have had only seventy men with him, including himself, could have displaced the government of Egypt from Itjtawy, and then held the Delta and Lower Egypt in a position of hostility to the rest of Egypt, even if he had brought all of his servants. The Egyptians were numerous, they had a mighty army at the time, and they had ruled over all of Egypt without division or interruption for nearly four hundred years until the time of Joseph and the time of the death of Jacob, mostly in the period known as the Middle Kingdom. The Word of God in the promises to Abraham informs us that Israel would be oppressed in Egypt, not that Israel would rule over Egyptians or any part of Egypt.

Furthermore, Jacob is depicted in Scripture as having had a humble disposition and having submitted himself to the rule of the pharaoh, while Joseph, in spite of the indications that his first loyalty was to his family, was also loyal to the pharaoh and there is no sign in Scripture that he had rebelled against him by usurping his authority. Rather, it is in the archaeological record that from the time of the later 12th Dynasty pharaoh Amenemhat III, the Egyptians had been permitting various Canaanite tribes to settle in various parts of the Delta in order to provide labor for building projects and other services [1]. There is truly nothing new under the sun, since the Egyptians had built the Prince’s Wall as a defense, but they still permitted “legal” immigration so that they could have a pool of cheap labor.

As we had described in our Genesis commentary, we believe that local chieftains among these Canaanite settlers, who had been called by the title pharaoh and whom the ancient historians and the archaeologists generally assign to the 14th Dynasty, were ultimately unified against the Egyptians in the 15th Dynasty which ruled Lower Egypt for about a hundred years. Some of these rulers had names similar to the names used by the Israelites, but that is only because they used a dialect of the Akkadian language which had also been used by the Hebrews. They were apparently far more numerous than the Israelites, at least before the Hyksos were driven out of Egypt, they were entrenched in Egypt for a much longer period, and they were in a much better position to be identified as the Asiatics who ruled Lower Egypt at this time than a few dozen of the sons of Jacob could have been.

In later Scriptures, and especially in the Wisdom of Solomon, the children of Israel in Egypt had been portrayed as humble guests of the Egyptians, who had ultimately been wronged and oppressed by them, for which reason the vengeance executed by Yahweh upon Egypt was fully justified. This is also the general impression projected in the beginning chapters of the Exodus account. In that it is apparent that the children of Israel were innocent bystanders under the rule of the Hyksos, and they were wronged by the Egyptian pharaohs who had overthrown the Hyksos, but they could never have wronged the Egyptians. Scripture never suggests that Israel ruled Lower Egypt, and historical circumstances show that there were indeed other Asiatic tribes in Egypt who had much greater numbers. We must therefore reject the idea that the Hyksos were Israel.

So now that we are about to endeavor a commentary of the prophet Isaiah, as a preface to that commentary, or perhaps as an appendix to our Genesis commentary, it is fitting that we offer a post-Genesis chronology, so that we may offer a plausible exhibition of the proofs that the historical circumstances which are illustrated in Isaiah certainly do agree with Assyrian history, the Biblical history of ancient Israel, and the chronology which the Scriptures offer in both the Old and New Testaments. The Scriptures are often criticized as being inaccurate in this regard, but the criticism is unjust, and we can indeed determine that the Bible is true, even if we are not provided quite enough information by which to understand every less significant chronological detail. But if we can properly explain the general circumstances of Biblical chronology from the Exodus though the periods of the Judges and Kings, we have better grounds on which to establish the veracity of Biblical history.

In this regard, Paul of Tarsus had made two statements, one in Acts and another in his epistle to the Galatians which we have already mentioned, which greatly assist our understanding of the chronology, but which are not always properly interpreted.

Although it came at a later time than the events recorded in Acts chapter 13, the first statement made by Paul which we shall discuss because it is relevant to our chronology here is found in Galatians chapter 3: “16 Now to Abraham and his seed were the promises made. He saith not, And to seeds, as of many; but as of one, And to thy seed, which is Christ. 17 And this I say, that the covenant, that was confirmed before of God in Christ, the law, which was four hundred and thirty years after, cannot disannul, that it should make the promise of none effect.” We do not need to explain the contentions which we have with the translation of verse 16 here, since we are only concerned with chronology. The first promises were made to Abraham in Genesis chapter 12, when he was seventy five years old, and by our chronology, the year was 1880 BC. The events of the Exodus and the giving of the law at Sinai we generally date to 1450 BC, which is four hundred and thirty years later.

The second statement Paul had made which is relevant to our chronology is found in Acts chapter 13, where Luke recorded him as having said: “17 The God of this people of Israel chose our fathers, and exalted the people when they dwelt as strangers in the land of Egypt, and with an high arm brought he them out of it. 18 And about the time of forty years suffered he their manners in the wilderness. 19 And when he had destroyed seven nations in the land of Chanaan, he divided their land to them by lot. 20 And after that he gave unto them judges about the space of four hundred and fifty years, until Samuel the prophet.” As we shall explain, this passage was not very well translated, however it is evident that Paul is dating the period of the judges to four hundred and fifty years, and with that we must agree.

So here we shall now explain how Paul’s four hundred and fifty year period immediately follows the end of his four hundred and thirty year period. The four hundred and thirty years ends at the Exodus, and then after the Exodus, Moses was the first of the men to judge Israel. Then we shall see how this period fits into the rule of the kings which had begun in the days of Saul. The four hundred and fifty years actually runs through the time of Saul, to the time that David became king of Israel, and we shall also explain that.

In Exodus chapter 7, we learn that Moses was eighty years old when he stood before Pharaoh, and in Deuteronomy chapter 34, he was a hundred and twenty years old when he died, and Joshua the son of Nun had already been prepared to take his place. So his tenure as the first judge of Israel was 40 years. While many Christians may not see Moses as one of the judges, we read in Exodus chapter 18 that “13 … it came to pass on the morrow, that Moses sat to judge the people: and the people stood by Moses from the morning unto the evening.” So that was essentially his function, to act as the judge of Israel while Yahweh led the children of Israel out of Egypt, and therefore his tenure must be included in Paul’s four hundred and fifty years. In fact, Moses had so much to judge, that he was urged later in that chapter to set up local, or petty judges among each of the tribes, who could judge more trivial matters, and he did so. Therefore we read near the end of the chapter “26 And they judged the people at all seasons: the hard causes they brought unto Moses, but every small matter they judged themselves.” So Moses was indeed the first in the line of the judges of Israel.

In Joshua chapter 14, Joshua explains that he was forty years old when Moses had chosen him along with the other men who were to spy out the land of Canaan, shortly after the Exodus and the giving of the law at Sinai. But the children of Israel were disobedient, and consigned to wandering forty years in the desert. Then a few years after the death of Moses, in Joshua chapter 14 (14:10) he professed to having been eighty five years old, no more than five years after the death of Moses. It is evident that the time from when Joshua and his fellows spied out the land of Canaan, to the time of the death of Moses, was not more than forty years, and Israel spent most of that time in the punishment of wandering in the wilderness. So we may reckon the period during which Joshua had judged Israel to have been from about the age of eighty to that of a hundred and ten, when he died, and therefore he was judge of Israel for 30 years. Therefore Joshua must have died some time around 1380 BC.

After the death of Joshua, in the book of Judges, a Mesopotamian king called Chushan-rishathaim had oppressed Israel for 8 years, and there was rest for 40 years before the Moabites oppressed them for 18 years. Then, where we are still in Judges chapter 3, there was rest for another 80 years. In Judges chapter 4, we read that the Canaanites had then oppressed Israel for 20 years. Then, as it is described in Judges chapter 5, following another 40 year period of rest the Midianites oppressed them for 7 years, until the time of Gideon. In Judges chapter 8 we are informed that Gideon had then judged Israel for 40 years, as it is described in Judges chapters 6 through 8. But here it is possible that Gideon’s 40 years may have at least partially overlapped the 7 year oppression of Midian. After that time, in Judges chapter 9, there is a man named Abimelech, who was apparently a lowly servant in Ephraim, and who had risen up to oppress Israel for 3 years, and after that two judges followed him, Tola for 23 years and Jair for 22.

After Gideon and these other judges, we are informed in Judges chapter 10 that the children of Israel were oppressed by the Philistines and Ammonites for 18 years, until the time of Jephthah which is described at the beginning of Judges chapter 11. This totals 319 years since the death of Joshua, 349 years since the death of Moses, and 389 years since the Exodus. The pertinent figure here is the 349 years, as we discuss the time of Jephthah.

At the beginning of the time of Jephthah, the king of the Ammonites had been oppressing Israel in the region east of the River Jordan, claiming that they had unjustly taken his land. So Jephthah sent to the king of Ammon and informed him that the Israelites had not occupied his land, as he had claimed, because they had taken it from the Amorites and had possessed it for 300 years at this time. This history is evident in the final years of the life of Moses, recorded in Numbers chapter 32 where we read in part: “33 And Moses gave unto them, even to the children of Gad, and to the children of Reuben, and unto half the tribe of Manasseh the son of Joseph, the kingdom of Sihon king of the Amorites, and the kingdom of Og king of Bashan, the land, with the cities thereof in the coasts, even the cities of the country round about.” The land which Israel had taken from the Amorites had, in more ancient times, belonged to the children of Ammon and the Amorites had taken it from them.

So in his letter, Jephthah had reckoned the time since the conquest of the kingdom of the Amorites and the occupation of their land by Israel towards the end of the life Moses as having been 300 years. But according to a linear and literal reading of the periods of the events in the Book of Judges up to this point, they seem to have possessed it for about 349 years, since Israel had conquered the land under Moses shortly before his death. If we add up all of the years of the periods described in Judges, as well as the years of Joshua, up to this point, the total is 349. But it is apparent that some of those events may have overlapped one another, and some of them may have been estimates of years which had been rounded by the original chroniclers who kept the records in Judges. For example, the manner in which Judges chapter 10 is worded does not rule out the possibility that the eighteen year period of Philistine and Ammonite oppression of Israel did not overlap the times of the judges which preceded Jephthah, as well as some of the time of Jephthah. Although it is also possible that Jephthah had only estimated the time, or rounded the numbers of years when he sent his message.

However we must also accept the probability that the scribes of ancient times must have been familiar with this 49-year discrepancy, and they were comfortable with it, knowing that the plain reading of the periods given in the early chapters of Judges were not intended to be chronologically precise. There may well have been other overlapping periods and other circumstances which were omitted in the concise language of the chroniclers.

Therefore it is apparent that in the Scriptures as they are today, elements of chronology are always debatable, because the Scriptures do not always provide accounts which are sufficiently comprehensive in order to readily derive a specific timeline of the order of events. So if we merely add up the numbers of years mentioned in the descriptions of the lives of Moses since the Exodus, and those of Joshua and the Book of Judges following the death of Joshua, we may find that the periods of time mentioned in Deuteronomy, Joshua and Judges spanning from the giving of the law at Sinai to the end of the Book of Judges is four hundred and sixty years, but that figure does not reckon the time of Samuel and Saul.

After the supposed 389 year period which we have just recounted, from the Exodus to the beginning of the time of Jephthah, we read at the end of Judges chapter 12 that Jephthah had judged Israel for 6 years, and three judges followed him: Ibzan, who judged for 7 years, Elon for 10 years, and Abden for 8. Then the final chapters of the Book of Judges concern themselves with the account of Samson, who is said to have judged Israel for 20 years, but this is explicitly said to have been entirely within the time that the Philistines had oppressed Israel for 40 years. This is recorded in in Judges chapters 13 and 15 (13:1 and 15:20).

So those periods from the time of Jephthah total 71 years in addition to the 389 years since the Exodus which we have just described, for a total of 460. But that is not the period which Paul was describing, and as we have seen where Jephthah had stated that Israel occupied the land for 300 years until his time, that is most likely a more accurate accounting of the duration of time covered by those first 10 chapters of Judges. Therefore the total is not 349 years, but 300, from Moses to Jephthah, and then from the time of Jephthah, 71 more, which is 371 years from the death of Moses to the end of the Philistine oppression. But Moses having been the first judge, that would be 411 years of Paul’s 450 years of the time of the judges, which leaves nearly another 40 years. Those 40 years are explained in the life of Samuel, the last judge of Israel before the rule of David as king.

So as we have said, some of those early periods described in Judges must have overlapped, since the time from the conquest of the land of Ammon from the Amorites shortly before the death of Moses, to the time of the beginning of the tenure of Jephthah is described as three hundred years, in Judges chapter 11 (11:26), when the dated events or circumstances given during that same period add up to about 349 years. But if there were overlapping periods in the years of the events described in those first 10 chapters of the book of Judges, and Jephthah was correct, then the period when he was judge would have started around 1110 BC, and, as we shall see, that better agrees with Paul’s statements and the four hundred and fifty years of Acts chapter 13. So that may also have been the same manner in which Paul had reckoned this chronology.

But even if Paul was not counting the life of Samuel, if he used the raw number of years from the Exodus through the Judges period, they add to 460 years, as we have said, and he could have rounded that figure, and it is not wrong. But it is unlikely Paul was reckoning his 450 years in that manner, .

If Jephthah’s account is correct, then the 6 years during which Jephthah was judge in Israel had spanned no later than from about 1110 to 1104 BC. Then the terms of the three judges who followed him, Ibzan, Elon and Abden, spanned another 25 years, from 1104 to 1079 BC. After that, the Book of Judges ends with a 40 year period of Philistine oppression which had evidently begun around 1079 BC, and ended around 1039.

450 Years – Acts 13:20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first Judge: |

|

|

|

|

|

Moses | 40 | 1450 | 1410 |

| (determined from age at death) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subsequent Judges or Periods after the conquest of the land of the Amorites: |

|

|

|

|

|

Joshua | 30 | 1410 | 1380 |

| (Joshua was 85 in Joshua 14:10, no more than 5 years after the death of Moses) |

Chushan-rishathaim | 8 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 3 |

“Rest” | 40 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 3 |

Moabites | 18 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 3 |

“Rest” | 80 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 3 |

King of Canaan | 20 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 4 |

“Rest” | 40 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 5 |

Midianites | 7 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 5 |

Gideon | 40 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 8 |

Abimelech | 3 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 9 |

Tola | 23 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 10 |

Jair | 22 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 10 |

Philistines and Ammonites | 18 |

|

|

| Judges chapter 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The sum of this period is 349 years, but we must amend it to 300 years based on Jepthah’s statement and the other reasons we have explained in the text. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Israel in Land of Ammon | 300 | 1410 | 1110 |

| Judges chapter 11 – Israel in land of the Amorites 300 years, according to Jephthah, although our total here is 389 years, some of these periods must have overlapped.. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jephthah | 6 | 1110 | 1104 |

|

|

Ibzan | 7 | 1104 | 1097 |

|

|

Elon | 10 | 1097 | 1087 |

|

|

Abden | 8 | 1087 | 1079 |

|

|

Philistines | 40 | 1079 | 1039 |

| Samson judges 20 years in the days of the Philistines. Judges 15:20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subtotal | 411 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The 450 years of Acts 13:20 must include the time of Samuel, who was also a judge of Israel, which ran through most of the reign of Saul. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saul | 40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total | 451 |

| Samuel very likely died the year before Saul’s death, so the total period of the judges is 450 years. |

|

|

Here many commentators err, by assuming that Samuel started to judge Israel, and Saul became king, after all of the events of the Book of Judges had passed. But the Philistines were still ruling over Israel even when Samuel had anointed Saul as king. Therefore it is likely that Samuel was born much earlier than the end of the Book of Judges and so was Saul, and that Saul became king some time before 1039 BC, which is also before the end of the Book of Judges. Samuel had anointed Saul as king as it is described in 1 Samuel chapter 8, but in 1 Samuel chapter 14 and later there were still garrisons of the Philistines in Israel. So the beginning of Saul’s rule as king over Israel and the forty-year period of the Philistine oppression of Israel described in the concluding chapters of Judges must have overlapped by at least a few years.

Furthermore, the four hundred and fifty years of the time of Paul is not yet expired until about 1000 BC, provided our estimate of the time of the Exodus is correct at about 1450 BC. If the 1450 date is off by a few years, as we have admitted that it may have been as early as 1455, that is fine and it is still relatively quite accurate. During the rule of Saul, Samuel was still alive and acting as a judge in Israel, and Samuel was still a judge in Israel in spite of the fact that Saul was king, and the time Paul described surely may have been fully independent of the rule of Saul. Samuel did not quit being judge when he anointed Saul, but rather, in 1 Samuel chapter 7 we read “15 And Samuel judged Israel all the days of his life.” That period included most of the rule of Saul, as Samuel only died a short time, perhaps as much as a year before Saul was killed in battle. Samuel maintained an authority greater than that of Saul throughout his life, and that is evident where Samuel had anointed David as king of Israel even though Saul had continued to hold the throne for perhaps another 14 or 15 years, as it is described in 1 Samuel chapter 16. So it is very likely that Paul reckoned the four hundred and fifty years to include the entire period of the judges, from the start with Moses in 1450 BC, to the death of Samuel, some time shortly before 1000 BC, before David took the throne and just before the death of Saul.

The death of Samuel is recorded in 1 Samuel chapter 25. Then in 1 Samuel chapter 28, Saul hired a necromancer to raise Samuel’s spirit from the grave, and he was successful. But Samuel was wroth with Saul, and prophesied his death at the hands of the Philistines, with whom he was still at war. A very short time later, within weeks or even days, Saul was killed in battle, as it is recorded in 1 Samuel chapter 31. So Samuel is the only prophet in Scripture to have prophesied beyond the grave. In the Book of Acts (13:20) Paul of Tarsus reckoned the period of the Judges as four hundred and fifty years, which would necessarily include the time of Samuel, who was the last judge of Israel, and therefore Paul’s four hundred and fifty years also includes nearly all of the rule of Saul.

But that assertion leads to a necessity to explain another problem. The reading of Acts chapter 13 in the King James Version may lead one to insist that the time of Saul must have followed the four hundred and fifty years which Paul had described, where we read: “20 And after that he gave unto them judges about the space of four hundred and fifty years, until Samuel the prophet. 21 And afterward they desired a king: and God gave unto them Saul the son of Cis, a man of the tribe of Benjamin, by the space of forty years.”

We can answer this in the Christogenea New Testament, where, in the passage in question, the verse divisions also differ somewhat, so the passage is quite different and reads, starting from verse 19 rather than verse 20: “… 19 and destroying seven nations in the land of Chanaan, He gave them their land for an inheritance 20 for about four hundred and fifty years. And in the course of these things He gave judges until Samuel the prophet. 21 And then they demanded a king and Yahweh gave to them Saul, son of Kis, a man from the tribe of Benjamin, for forty years.”

With this it may be justly argued that the time of Samuel, and therefore the time of Saul, were included where Paul had said “in the course of these things” so that those events are reckoned along with the period of four hundred and fifty years described there by Paul. The time of the last forty years in the life of Moses must also have been included in that four hundred and fifty years, since “the course of these things” must also have included the time of “destroying seven nations in the land of Chanaan”, and the first of those battles with the Canaanites happened as soon as Exodus chapter 17 and had continued until, and beyond, Moses’ death, once again, “in the course of these things.”

So in the perspective of Paul’s four hundred and fifty years, the later time of Moses must have been included, and the time of Saul must have been included, since most of it also coincided with the time of Samuel until Samuel’s death. Then, the time of Saul must have also partially overlapped with the rule of the Philistines during the last 40 years of the Judges period. This is fully evident where as late as 1 Samuel chapter 14 there were still garrisons of the Philistines in Israel, and Saul did not even take an initiative against the Philistines until after his second year, as it is described in 1 Samuel chapter 13.

If we accept the account of Jephthah, and add the times which follow his in the Book of Judges to his three hundred years, which began shortly before the time of the death of Moses, there are 71 years left in Judges. So this reckoning of the chronology gives the end of the period of the final Philistine oppression of Israel as having been around 1039 BC. During this period, Samuel had anointed Saul as king as it is described in 1 Samuel chapter 8, but in 1 Samuel chapter 14 there were still garrisons of the Philistines in Israel. So the beginning of Saul’s reign over Israel and the forty-year period of the Philistine oppression of Israel described in the concluding chapters of Judges must have overlapped by at least a few years. According to 1 Samuel chapter 13, where Saul did not even move against the Philistines until he had been king for two years, his rule could not have started less than two years before the end of that last 40-year period in Judges, or some time around 1042 BC. However, as we shall see, the rule of Saul and the Philistine oppression of Israel must have overlapped even more than those two or three years, but we cannot precisely determine the actual time.

Simply because Saul chose to move against the Philistines after his second year, which is in his third year, does not mean that the oppression had been lifted. So some time later, a span which must have been significant but which really cannot be determined, the Philistines are camped in a town of Judah, in 1 Samuel chapter 17, and David arrives to slay their champion, Goliath. Up to that point, the Philistine were mocking Israel, and we would mark this event as the beginning of the end of the Philistine oppression, even if it cannot be pinpointed precisely. (Later we shall see that there are problems with that also.) From this point, the Philistines fled from David, or they were slain by him and his troops. But they continued to harass Saul as Saul had also been persecuting David, apparently for at least a decade or more until the time of his death.

In 2 Samuel chapter 5 we read that “4 David was thirty years old when he began to reign, and he reigned forty years.” While according to the law a man does not go to battle until he is twenty years old, that is a law of conscription, and it does not necessarily forbid a younger man from participating in a battle. Where David’s youth was surprising when he appeared to announce that he could slay Goliath, in 1 Samuel chapter 17, he may indeed have been younger than twenty. So if David was 16 years old when he slew Goliath, then he had 14 years with Saul as king before He himself had become king of Judah in Hebron at the age of 30. But of course, this is conjecture and it could be off a couple of years.

In Acts chapter 13 (13:21), as we have translated the passage, Paul of Tarsus is recorded as having said “21 And then they demanded a king and Yahweh gave to them Saul, son of Kis, a man from the tribe of Benjamin, for forty years.” So this seems to infer that Saul was king of Israel for forty years, and a good portion of that time was in the forty years during which the Philistines had oppressed Israel. But otherwise, the Scripture never informs us of the duration of the rule of Saul, so we do not know how Paul had concluded that it was forty years. That does not mean that we should doubt Paul, however Flavius Josephus, in Antiquities Book 10 (10:143) gives the duration of Saul’s rule as twenty years, although it should not be taken for granted that he is accurate.

Counting Backwards

Sometimes it is better to count backwards when deducing a chronology, rather than forwards. So here we are going to do that with the lines of the kings of Israel and Judah. Doing this, we will use an anchor date for the fall of Samaria which is well known in archaeology and ancient history, which is 722 BC. In an ancient Assyrian inscription from the reign of king Sargon II, we have the following text:

At the beginning of my royal rule, I … the town of the Sama]rians [I besieged, conquered] (2 lines destroyed) [for the god … who le]t me achieve (this) my triumph. . . . I led away as prisoners [27,290 inhabitants of it (and) [equipped] from among [them (soldiers to man) ] 50 chariots for my royal corps. … [The town I] re[built] better than (it was) before and [settled] therein people from countries which [I] myself [had con]quered. I placed an officer of mine as governor over them and imposed upon them tribute as (is customary) for Assyrian citizens. [2]

By the popular chronologies, it is apparent that Sargon II’s predecessor, Shalmaneser V, had besieged Samaria. This is also evident in 2 Kings 18:9 where we read “9 And it came to pass in the fourth year of king Hezekiah, which was the seventh year of Hoshea son of Elah king of Israel, that Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria, and besieged it.” However Shalmaneser either died or was killed in 722 BC, and his successor Sargon II took credit for the final victory. The Scripture mentions Sargon in Isaiah chapter 20, but does not explicitly attribute the taking of Samaria to him, where it is described in 1 Kings chapter 18.

Therefore, beginning from 722 BC and counting backwards, we shall assess the periods of the kings of Israel and Judah. But this is complicated by the fact that there were some overlapping reigns, or periods of co-regency which are not always explicitly explained in Scripture. For this, a fair explanation exists in a paper by Edwin R. Thiele of Andrews University, titled The Problem of Overlapping Reigns. So these dates overlap somewhat, while we cannot take the time here to explain all of the reasons for the overlap in detail, they are discovered in a comparison of the Biblical history of interactions between the kings of Israel and Judah, as well as the chronicles of Assyria. One day we do hope to do a more detailed study of our own, and when we discuss the early kings of Judah it will be apparent why that is necessary.

The last king of Israel, Hoshea, had ruled Israel for 9 years, which must have begun around 731 BC (2 Kings 17:1). Before him, Pekah ruled for 20 years, which began in 742 BC (2 Kings 15:27). [I am aware that this leaves space for only ten years, but that is also all the dating of other passages would allow.] Before him, Pekahiah ruled for 2 years, from 742 to 740 BC (2 Kings 15:23). Before Pekahiah, his father Menahem ruled for 10 years. From 752 to 742 BC (2 Kings 15:17). Menahem had slain Shallum, who ruled Israel for only 1 month, about 752 BC, and Shallum had slain Zachariah, who ruled for only 6 months that same year, but which may have overlapped 753 into 752 BC. The father of Zachariah was the notable but wicked king Jeroboam II, who ruled Israel for 41 years, from 793 to 753, or perhaps 752 BC (2 Kings 14:23). But the father of Jeroboam II, Jehoash, or sometimes he is called Joash, ruled Israel for 16 years, which were evidently from 798 to 782 BC (2 Kings 13:10). That is an overlap of 11 years with his son Jeroboam. The 11 year overlap is apparent in Scripture, where Jeroboam is said to have become king in the 15th year of Amaziah, king of Judah, in 2 Kings 14:23, and Amaziah was said to have been king of Judah for 29 years. But in 2 Kings 15:1, after 14 years, Amaziah, who then died, is said to have been succeeded by his son Azariah in the 27th year of Jeroboam king of Israel. The additional years can only be accounted if Jeroboam had his first 11 or so years as a co-regent with his father.

Before Jehoash, his father Jehoahaz had ruled Israel for 17 years, from 814 to 798 BC (2 Kings 13:1), and before him, his father Jehu, who destroyed the house of Ahab, ruled for 28 years, from 841 to 814 BC (2 Kings 10:36). Ahab had two wicked sons with Jezebel. The last to rule was Jehoram, or Joram, who ruled Israel for 12 years from 852 to 841 BC (2 Kings 3:1), and before him his brother Ahaziah for 2 years, in 853 and 852 BC (1 Kings 22:51). Ahab their father ruled before them for 22 years from about 874 to 853 BC (1 Kings 16:29). This king is called “Ahab the Israelite” where he is mentioned as having sent 10,000 foot soldiers in a coalition with Damascus, Hamath and other cites of the Levant against the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, who ruled Assyria from 858 to 824 BC. [3] The event, dated to the early years of his rule, helps to corroborate this aspect of this chronology, as it would have occurred in the later years of Ahab’s rule. Before Ahab, his father Omri had ruled Israel for 12 years, from 885 to 874 BC (1 Kings 16:23), and before him, a man named Zimri had taken the throne by treason, destroyed the house of Baasha, and ruled for only seven days before Omri had slain him to become king (1 Kings chapter 16).

The son of Baasha was Elah, who ruled Israel for 2 years in 886 and 885 BC (1 Kings 16:8), and his father had ruled for 24 years, from 909 to 886 BC (1 Kings 15:33). Baasha was of the tribe of Issachar, and had usurped the throne from Nadab the son of Jeroboam I, an act which the text of 1 Kings chapter 15 attributes to an act of punishment for sin where we read that “30 Because of the sins of Jeroboam which he sinned, and which he made Israel sin, by his provocation wherewith he provoked the LORD God of Israel to anger.” So before Baasha slew him, Nadab ruled Israel for 2 years, in 910 and 909 BC (1 Kings 15:25). Before Nadab, Jeroboam I ruled Israel, after he was given the rule over the ten northern tribes upon the division of Solomon’s kingdom. So Jeroboam ruled Israel for 22 years, from 931 to 910 BC.

David and Solomon are each described as having ruled Israel for forty years (2 Samuel 5:4, 1 Kings 11:42). So according to this admittedly rough chronology that period of time would span from about 1011 BC to 931 BC. Therefore, hypothetically speaking, if Saul had become king in Israel, and ruled forty years, from 1051 BC, there would have been about 12 years of the oppression of the Philistines remaining, and it is evident in the rule of Saul that he fought with the Philistines for much longer than that, since he died at their hands. But if David became king of Israel at the age of 30 in 1011 BC, he could not have been known by Saul for much longer than 14 years, or from 1025 BC, if he were 16 when he slew Goliath. This is plausible, if the end of the Philistine oppression in Judges comes not long after the time that Saul finally decided to drive out the Philistines, in the 3rd year of his reign, as it is described in 1 Samuel chapter 13.

In any event, counting backwards from the destruction of Samaria in 722 BC, and coming to 1011 BC, we see that there are 28 years between that time, and the time at which we had reckoned the end of the period of Philistine oppression of Israel in the days of Saul, which is 1039 BC. During those 28 years, it is likely that Saul ruled Israel, and that David was introduced to the people when he slew Goliath. There are further details which we may be able to sort out, or errors which we may be able to correct in the future, but with this we see that the general Biblical narrative in this aspect is not in conflict with itself, and does indeed align with ancient history. But not without a problem of ten years, which is evident in the chart below:

Kings of Israel |

|

|

|

|

Hoshea |

| 9 | 721? | 712? |

Pekah |

| 20 | 740 | 721? |

Pekahiah |

| 2 | 742 | 740 |

Menahem |

| 10 | 752 | 742 |

Shallum |

| 1 month | 752 | 752 |

Zechariah |

| 6 months | 753 | 752 |

Jeroboam II |

| 41 | 793 | 753 |

Jehoash (Joash) |

| 16 | 798 | 782 |

Jehoahaz |

| 17 | 814 | 798 |

Jehu |

| 28 | 841 | 814 |

Jehoram (Joram) |

| 12 | 852 | 841 |

Ahaziah |

| 2 | 853 | 852 |

Ahab |

| 22 | 874 | 853 |

Omri |

| 12 | 885 | 874 |

Zimri |

| 7 days | 885 | 885 |

Elah |

| 2 | 886 | 885 |

Baasha |

| 24 | 909 | 886 |

Nadab |

| 2 | 910 | 909 |

Jereboam I |

| 22 | 931 | 910 |

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

Solomon |

| 40 | 971 | 931 |

David |

| 40 | 1011 | 971 |

Saul |

| 40 |

| 1011 |

Now we shall try to briefly discuss the kings of Judah in this same manner that we have the kings of Israel. But because of problems with this chronology which are quite nagging from the time of Jehoram to that of Hezekiah, we shall have to leave this for better clarification at another time. During that time, there is one co-regency which is evident in Scripture, in the time of Jehoshaphat and his son Jehoram, but there also must have been other overlapping reigns. In his paper on overlapping reigns, which we have already cited, Edwin Thiele described some of the issues with understanding the period from the time of Athaliah to that of Azariah especially, as the durations of their rule add up to too many years, unless there were co-regencies.

One source attempts to rectify this in part by moving up the date of Hezekiah’s rule by ten years. To begin in 716 BC rather than 726, and give him a co-regency of 10 years with his young son Manasseh. But if that occurred, then Hezekiah could not have been king when Samaria fell in 722 or 721 BC. So we shall only discuss the kings of Judah to the time of Hezekiah here, which is also the time of Isaiah.

The general date for the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II is sometimes given as 587 BC, and sometimes as 586 BC [4], which we prefer. Leading up to the time of that event, Zedekiah had ruled Judah for 11 years, from 597 to 586 BC (2 Kings 24:18). Before him, Jehoiachin (who was also called Coniah and Jeconiah) was king for three months, which may have spanned 598 to 597 BC (2 Kings 24:8). His father Jehoiakim, whose name was originally Eliakim, had ruled Judah for 11 years, from 609 to 598 BC (2 Kings 23:36). Much of this is corroborated in surviving Babylonian inscriptions from 605 BC and later, which is the year that Nebuchadnezzar II is estimated to have become king of Babylon.

This Jehoiakim was given that name by the king of Egypt, Pharaoh Necho, who came to Jerusalem and deposed his brother Jehoahaz after he had ruled for only 3 months (2 Kings chapter 23, 2 Chronicles chapter 36). This Necho was also mentioned in the writings of the historian Herodotus, as having led a short-lived revival of Egypt at this time, and his exploits in Syria are recorded there. In Book 2 of his Histories (2:159), Herodotus recorded a battle between pharaoh Nacho and the Syrians at Migdal, which must be the battle in which Josiah king of Judah was slain, as it is recorded in 2 Kings chapter 23. In that chapter it is described that Necho was actually going through Palestine to confront the king of Assyrian, but Josiah had intercepted him, and was killed. That involved Necho in the affairs of Jerusalem, at least for a few years until the coming of Nebuchadnezzar. So Josiah, the father of Jehoahaz, had ruled Judah for 31 years, from 641 to 609 BC (2 Kings 22:1).

Before Josiah, his father Amon ruled Judah for 2 years, from 643 to 641 BC (2 Kings 21:19), and before Amon, his father Manasseh ruled Judah for 55 years, from 697 to 643 BC (2 Kings 21:1). Before Manasseh, king Hezekiah ruled in Judah for 29 years, from 726 to 697 BC (2 Chronicles 29:1). This accords with the Assyrian inscriptions from the time of the siege of Jerusalem shortly before 700 BC, in which Hezekiah is named explicitly, and also with 2 Kings 18:10 which places the fall of Samaria in the 6th year of Hezekiah, which would have begun in 721 BC but which is estimated by archaeologists to have occurred in 722 BC. This also accords with a passage at 2 Kings 18:9 which we have already cited here, which informs us that Shalmaneser besieged Samaria in the seventh year of Hoshea king of Israel, which was the fourth year of Hezekiah. While we have Hezekiah’s reign beginning in 726 BC, that may compel us to move it to at least 727 BC.

Kings of Judah |

|

|

|

|

Zedekiah |

| 11 | 597 | 586 |

Jehoiachin (Coniah, Jeconiah) |

| 3 Months | 598 | 597 |

Jehoiakim |

| 11 | 609 | 598 |

Jehoahaz |

| 3 Months | 609 | 609 |

Josiah |

| 31 | 641 | 609 |

Amon |

| 2 | 643 | 641 |

Manasseh |

| 55 | 697 | 643 |

Hezekiah |

| 29 | 726 | 697 |

Then before Hezekiah, it is written that Ahaz ruled for 16 years, Jotham for another 16, and then Azariah, who was also called Uzziah, for 52 years, however from the time of those kings and earlier, the chronology becomes problematical. If we accept those periods at face value, Azariah ruled as king of Judah from 810 to 758 BC. Isaiah had professed that the beginning of his ministry was in the time of this Azariah, or as he called him Uzziah. The prophets Hosea and Amos had also both professed to have begun their ministries in the days of Azariah, or Uzziah, and Micah started a short time later, in the days of Jotham. However it is apparent that none of these men prophesied as long as Isaiah had prophesied. But this would mean that Isaiah had a ministry which spanned at over 60 years, since he was still prophesying after the death of Hezekiah in 697 BC. But perhaps Isaiah’s ministry was not that long.

In 2 Kings chapter 15 we read “23 In the fiftieth year of Azariah king of Judah Pekahiah the son of Menahem began to reign over Israel in Samaria, and reigned two years.” So according to our chronology of the kings of Israel, the 50th year of Azariah must have been about 742 BC, so his rule must have began around 791 BC, and he must have had a co-regency with his own son, Jotham. But even that is problematical, since there would be only about 13 years between Azariah and Hezekiah, wherein two men, Jotham and Ahaz, are each said to have ruled for periods of 16 years. So there must have been co-regencies, especially in the time of the long-lived Azariah.

There is one earlier co-regency which is clearly evident in Scripture, as Jehoram must have shared the rule with his father Jehoshaphat for several years. According to 2 Kings chapter 8 (8:16), Jehoram became king of Judah in the fifth year of Jehoram of Israel, when his father Jehoshaphat was (still) king of Judah, indicating a co-regency. Jehoram took the throne at the age of 32 and reigned for 8 years. There we read: “16 And in the fifth year of Joram the son of Ahab king of Israel, Jehoshaphat being then king of Judah, Jehoram the son of Jehoshaphat king of Judah began to reign.” But at that time Jehoshaphat had not yet died, but neither is there any readily apparent way to tell how long the co-regency had lasted.

In 1 Kings chapter 16 we read “29 And in the thirty and eighth year of Asa king of Judah began Ahab the son of Omri to reign over Israel: and Ahab the son of Omri reigned over Israel in Samaria twenty and two years.” Since we have a fair chronology of the kings of Israel, and the time we assign to Ahab is approximately corroborated in Assyrian records, then Omri having become king about 885 BC it is apparent that Asa was already king in Judah for over 37 years, or from about 922 BC. Then Abijam his father, who was king for only 3 years, had apparently ruled from about 925-922 BC, and Rehoboam his father for 17 years, from 942-925 BC.

However even this is apparently 11 years too soon for our chronology of Israel, so the chronology of the early years of the kingdom of Judah is problematic as early as the time of Asa, or perhaps, even of Rehoboam. Yet the duration of our chronology of Israel is better attested in historical records, both in the times of Omri and Ahab, whose names appear in nearly contemporary Assyrian inscriptions, and again in the time of Hoshea, at the end of which Samaria had been destroyed.

So even if we have not yet completed a chronology for Judah, there is only a question of a few dozen years, and there is one other issue to address, which is where in some chronicles, every part of a year, no matter how small, is counted as a full year. However here we do hope to have established the fact that the chronologies are historical, and that they can indeed be fit into the space provided, from the time of the end of the judges period and Paul’s four hundred and fifty years, to the time of the destruction of Samaria, and from the time of Hezekiah to the destruction of Jerusalem. In between the time of Solomon and Hezekiah are about 205 years and 12 kings of Judah, including the woman usurper, Athaliah. But the stated duration of their rule is 254 years so there must have been several co-regencies, and perhaps many fractions of years counted as full years.

| Chronology Not Conclusively Determined: | ||||

| Ahaz | 16 | 734 | ||

| Jotham | 16 | 741 | ||

| Azariah (Uzziah) | 52 | 791 | 739 | |

| Amaziah | 29 | |||

| Joash | 40 | |||

| Athaliah | 6 | |||

| Ahaziah | 1 | |||

| Jehoram | 8 | |||

| Jehoshaphat | 25 | |||

| Asa | 41 | |||

| Abijam (Abijah) | 3 | |||

| Rehoboam | 17 |

To illustrate the problems with this, I will cite a section of Edwin Thiele’s paper on overlapping reigns:

A further difficulty arises when the totals of Israel and Judah are compared with the totals of the Assyrian rulers of this century. This is a period when Assyrian chronology is well established, and when there was close correlation between Hebrew and Assyrian history. Shalmaneser III of Assyria in the eighteenth year of his reign claims the receipt of tribute from Jehu, which was 841 B.C. (here we have dated Jehu’s reign to have begun in that year) and Tiglath-pileser III mentions a campaign against Azariah and Menahem that took place between 743 and 738 B.C. (we have dated Menahem to have ruled from 752 to 742, and Azariah from 791 to 738 BC.) So from Assyrian sources we know that the period involved was in actuality about one hundred years, and certainly not 114 or ll5, or 128. (Speaking of a portion of the seemingly extra years in this chronology of Judah.)

Regarding the difficulties of this period, Sanders has expressed himself as follows: "The exact chronology of this century is beyond any historian's power to determine.... What to do with the extra twenty-five years is uncertain."

Other historians of the period cited by Thiele were evidently exasperated with these problems to the point where one of them had claimed that there must have been intentional mutilations of the text. But here we shall suspend our discussion of the chronology of the kings of Judah before the time of Hezekiah until we can take the time to research it more deeply for ourselves.

Chronology, as well as intentional mutilations of the texts, have evidently been a challenge for a very long time. For example, we read in Josephus’ Antiquities of the Judaeans, in Book 8 (8:61-62) that: “61 Solomon began to build the temple in the fourth year of his reign, on the second month, which the Macedonians call Artemisios, and the Hebrews Zif, five hundred and ninety-two years after the Exodus out of Egypt; but one thousand and twenty years from Abraham's coming out of Mesopotamia into Canaan, and after the deluge one thousand four hundred and forty years; 62 and from Adam, the first man who was created, until Solomon built the temple, there had passed in all three thousand one hundred and two years. Now that year on which the temple began to be built was already the eleventh year of the reign of Hiram; but from the building of Tyre to the building of the temple, there had passed two hundred and forty years.”

So according to Josephus, if Solomon began his rule as we estimate it, in 971 BC, his 4th year would begin in 968 BC. So the Exodus would have been in 1559 BC, where we have 1450. The sojourn of Abraham into Canaan would have been in 1988 BC, where we have 1880. The flood of Noah would have been in 2408 BC where we have 3187, and the creation of Adam in 4070 BC, where we have 5449. So Josephus had evidently already been using a manuscript which was altered greatly from the Septuagint, and closer to what we see today in the Masoretic Text, and he was writing his Antiquities some short time after 70 AD.

Where Josephus had said that the city of Tyre had been built 240 years before the temple, or around 1208 BC, he had evidently been citing the translation of the ancient Chronicles of Tyre which had been translated by Hecataeus of Abdera, which he had cited in another of his writings, Against Apion. In Scripture, Tyre is an Israelite city. In the books of Joshua and Judges it was not listed among the cities where Canaanites remained. Here we see that it was built some time around 200 years after the death of Moses, which is close to the time of Deborah and Barak, in Judges chapter 5, when they defeated the Canaanites under Sisera, after which time it was said that Dan was at sea, and Asher abode in his breaches, or ports on the sea. Tyre was certainly one of those ports.

Footnotes

1 Ancient Egypt, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egypt, accessed July 18th, 2024.

2 Ancient Near Eastern Texts Related to the Old Testament 3rd edition, James Pritchard, editor, 1969, Harvard University Press, p. 284

3 ibid., pp. 276-279.

4 Nebuchadnezzar, Bible Odyssey, https://www.bibleodyssey.org/articles/nebuchadnezzar/, accessed July 19th, 2024.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.