On Genesis, Part 19: The Appearance of the Sons of Noah

On Genesis, Part 19: The Appearance of the Sons of Noah

Now that we have completed our exhibition of the historical identity of the nations of the sons of Noah as they are described in Genesis chapter 10, we are going to take a respite in order to describe the physical appearance of at least some of the sons of Noah as it is revealed in both the history and the archaeology of those nations, or that of their neighbors. As we had asserted earlier in this commentary on Genesis, in our discussion of the tribes of The Japhethites listed in Genesis chapter 10:

Any honest man who studies archaeology and history and who reads Genesis chapter 10 from the perspective of classical antiquity, where one must consider the nations of the sons of Noah in their ancient forms rather than in their modern conditions, must ultimately face the fact that all of the descendants of Noah were originally White, or what was called in the past Caucasian or considered to be related to modern [White] Europeans. As a digression, the words of the prophets also explain the modern condition of those nations, and we may make some references in that regard as we discuss them here. In the 19th century, White Europeans were termed Caucasian because learned men who studied this aspect of history had realized that to a great extent, the early settlers of Europe had migrated from Mesopotamia and the ancient Middle and Near East by travelling through the region of the Caucasus Mountains. That view is oversimplified, but for many of our Keltic or Germanic or even Slavic ancestors it is certainly true. Others had come from the east at an even earlier time, in which most of them had migrated by sea rather than by land.

Now we hope to prove that assertion, and if we can prove that merely one nation each which had descended from Ham, Shem and Japheth were White, then it must be admitted that the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches have been lying about Genesis for centuries, and that all of the sons of Noah must have been White.

However, there are very few detailed written descriptions of the physical appearance of people in the surviving ancient inscriptions from Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Persia, the Levant and even Egypt. Perhaps they were not necessary, since the world was more or less homogeneous, or appeared to be homogeneous even with the presence of the Nephilim. There are some telling remarks, such as descriptions of hair standing up from fear or faces going pale and other similar statements in various legends. For example, in the Epic of Gilgamesh there is an account of Enkidu’s face having grown pale after hearing of some of the injustices committed by Gilgamesh. [1] In the Descent of Ishtar to the Netherworld, an ancient Akkadian myth which was also found in Sumerian, where Ishtar was known as Inanna, upon hearing of the arrival of Ishtar at the gates of the netherworld, Ereshkigal, the queen, is depicted as having heard the news and we read that “Her face turned pale like a cut-down tamarisk, while her lips turned dark like a bruised reed.” [2]

In the ancient Egyptian Admonitions of Ipu-Wer, which date to as early as the beginning of the 24th century BC, there is a premonition of societal decay, because aliens had been admitted as citizens, where in the opening lines it warns: “Door [keepers] say: ‘Let us go and plunder.’ … The laundryman refuses to carry his load .… Bird-watchers] have marshaled the battle array [Men of] the Delta marshes carry shields…. (5) … A man regards his son as his enemy.… A man of character goes in mourning because of what has happened in the land.… Foreigners have become people everywhere.… 4 Why really, the [face] is pale. The bowman is ready. Robbery is everywhere. There is no man of yesterday…” The Egyptian prophet to whom the words are attributed, Ipu-Wer, was denouncing the king for the state of the nation as aliens were admitted into the land and given rights, and the lamentation that “the face is pale” since “robbery is everywhere” precipitates a long list of similar woes. [3]

It is doubtful that a society of dark-skinned and wiry-haired arabs or negros would even have such analogies in their vocabulary. Otherwise, we must depend on the works of art left behind by ancient peoples, and often the art must be interpreted, as the styles employed by ancient artists do not always reflect natural realities. However ancient works of art have often lost the colors in which they were originally painted, and this is always the case where the works were left exposed to the elements. But in many Egyptian paintings the color has survived, because they are found in the tombs of Egypt which laid virtually undisturbed, and often buried in the sand for many centuries.

[1 Ancient Near Eastern Texts, p. 78; 2 ibid., p. 107; 3 ibid., p.441.]

Much fodder is made from the idiom “black-headed people” which first appeared in inscriptions in ancient Sumer, but which was used by both Sumerian and Assyrian rulers throughout ancient history, most often in Assyrian building inscriptions and similar royal inscriptions. There are claims that the reference is to ethnic Sumerians, or perhaps to ethnic Babylonians, as having been a negro people. But that is not true. In a 2020 article by one Mattias Karlsson titled From Sumer to Assyria : The term ‘black-headed people’ in Assyrian texts, the author collected 48 middle and late Assyrian uses of the term, which show beyond doubt that the idiom was used only to describe the commoner, as opposed to the king as their shepherd, and the author addresses and explains seemingly contradictory meanings and concludes that “The partly contradictory meanings may be explained by the use of the term in different political contexts (from city-states to empires).”

In other words, the term “black-headed people” describes only those people over whom a particular king had ruled at the time when the phrase was used, as the king saw himself as the shepherd of the people, and used that term to describe his function. Karlsson also concludes, in regard to the term’s use throughout Assyrian history, that “As for thematic variation, it is telling that the shepherding theme is expressed in both the first and final attestation of the term. The texts are separated from each other by seven centuries, thus showing the continuity of the theme.” In other words, its use is consistent from the earliest to the latest inscriptions in which it was found. The seven centuries to which the author refers end with the 7th century BC and the time of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon, and later in that century the Assyrian empire had come to an end. Reading the inscriptions where the term appears, we would have to agree with Mattias Karlsson. There were no negros of which to speak in ancient Mesopotamia, and this ancient idiom cannot honestly be used to prove that there were. [4]

[4 From Sumer to Assyria : The term ‘black-headed people’ in Assyrian texts, Mattias Karlsson, Akkadica, 141/2 (2020), pp. 127-139.]

In the ruins of the ancient Sumerian, and later Akkadian, city of Eshnunna, and those of the nearby subject city of Tutub, which are found at sites now called by the Arab names of Tell Asmar and Khafajah, statues and other works of art esteemed to date to the 3rd millenium BC have been discovered by archaeologists. The findings are described in a book titled Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafājah, which was published in 1939. In this volume, many of the sculptures of human heads are described as having eyes of lapis lazuli, which is a blue stone, although others had eyes of bitumen. [5] Speaking of a dissimilar statue found amongst a hoard of otherwise homogeneous statues which had been discovered in a structure called the Square Temple, the name given by archaeologists, the author states in part that: “The material differs from that of all the other statues; it is semi-translucent alabaster of a dark amber color.” Then after speaking of both the contrasting and similar aspects of this and the other statues, the author states that “… alabaster, like marble, is much more suitable for suggesting the peculiar appearance of flesh than is the more opaque gypsum of most of the other statues…” and he goes on to doubt whether the dark amber statue was even made in Eshnunna for that very reason. [6] Both alabaster and marble are typically white or close to white in color, although other shades are possible. Most of the statues of this hoard are freely available for viewing on the internet if one searches for the term “Tell Asmar hoard”, and they are all made from light-colored or whitish-looking stone. [7] So the author understood the fact that the makers of the statues had, at least usually, chosen their material according to how they wanted to represent the color of their skin. Gypsum is also typically white, but sometimes colorless, and is the main ingredient in modern plasterboard and chalk. It was used for sculpture in Egypt, Mesopotamia and Rome. [8] We may argue that bitumen may have been used for the eyes on some statues only because lapis lazuli is semi-precious and therefore it was much more rare and for that reason, more expensive. [9]

[5 Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafājah, Henri Frankfort, The University of Chicago Press, 1939, p. 56 ff.; 6 Frankfort, p. 25; 8 Tell Asmar Hoard, 7 Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tell_Asmar_Hoard, accessed June 21st, 2023; 8 Gypsum, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gypsum, accessed June 22nd, 2023; 9 Lapis Lazuli, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lapis_lazuli, accessed June 22nd, 2023.]

In an ancient Egyptian literary work titled “A Hymn to Amon-Re”, the oldest known example of which is dated to the Egyptian empire of approximately 1775-1575 BC, there is a line which states: “Atum, who made the people, Distinguished their nature, made their life, And separated colors, one from another…” [10] In an introductory note to the hymn the editors explain that: “Egypt's world position under her Empire produced strong tendencies toward centralization and unification of Egyptian religion, with universalism and with syncretism of the gods….” [11] This prayer fully reflects the syncretism of religious beliefs of subject peoples which empires historically impose on their subjects. Other Egyptian inscriptions also reflect the understanding that the peoples of sub-Saharan Africa were black, and that they were separated by their color, at least from the Egyptians themselves.

[10 Ancient Near Eastern Texts, p. 366; 11 ibid., p. 365.]

In a book about Egyptian history originally titled The Burden of Egypt, after a prophecy in Isaiah, but later renamed The Culture of Egypt, the author describes a tomb which is conventionally dated to about the 26th century BC: “The tomb of a Fourth Dynasty queen has shown that Khufu’s daughter, Hetep-hires II, had blond hair. The extant colors on the tomb wall show her hair as yellow, with fine red lines, in contrast to the conventional black elsewhere in this tomb and the rest of the cemetery. One assumes that such a blond strain was introduced into Egypt from the Tjemeh-Libyans lying to the west of the Nile Valley, a people of European connections and apparently of considerable wealth in herds of cattle. Another strain of evidence comes from the examination of the so-called ‘fourth pyramid’ of Gizeh, actually a benchlike tomb in the form of a huge sarcophagus. This last important structure of the Fourth Dynasty was built for Queen Khent-kaus, who carried the legitimate line from the Fourth to the Fifth Dynasty. Here we have the origin of the later legend that the courtesan Rhodopis, that is, ‘rosy-cheeked,’ who was the ‘bravest and fairest of her day, fair-skinned and rosy-cheeked, built the third pyramid.’” [12]

[12 The Burden of Egypt, An Interpretation of Ancient Egyptian Culture (later renamed The Culture of Egypt), John A. Wilson, The University of Chicago Press, 1951, pp. 97-98.]

Here we would argue with the author of The Burden of Egypt, because his comments about the daughter of Khufu having had blonde hair from Libyans, whom he then associates with Europeans, is all pure conjecture. As for the legend of Rhodopis, the ancient Greeks certainly did consider both Egyptians and Libyans, who were also of Ham, to be very much like themselves. For example, in his Suppliant Maidens, which is a parody of the story of the flight of the Danaans from Egypt to Greece, the tragic poet Aeschylus considered Danaus and Aegyptus to have been brothers. [13] Elsewhere in that same work the poet has the king of Argos mention several races and compares the likeness of their women to those of the Greek Danaans. Among those mentioned are Libyans, Egyptians and Amazons. The list indicates the perception of a large degree of homogeneity among these peoples, because the king is depicted as having contrasted them solely by certain behavioral customs, and not by their natural appearance. [14]

[13 Suppliant Maidens, Aeschylus, lines 321-323; 14 ibid., lines 277-290]

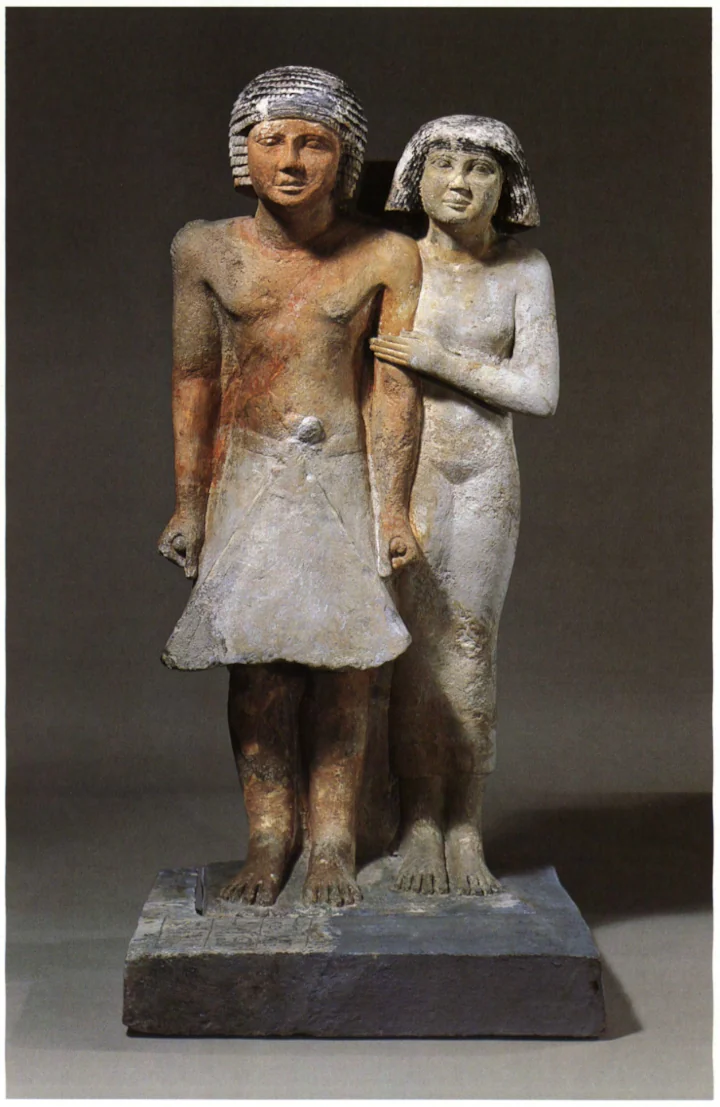

However in Egyptian art, the colors employed had represented the traditional roles of women and men in society. In a book titled Ancient Egypt, Treasures From the Collection of the Oriental Institute there is a description of a model of a mill workshop from the 9th or 10th dynasties of Egypt, the 22nd or 21st centuries BC, where we read the following, in part: “Baking and brewing were closely associated, for beer was made from bread mash. The first step in the process is represented by a woman bent over a hand mill, grinding grain into flour…. Another woman seated near the mill assists, collecting the flour into a basket…. Most of the figures employed in bread and beer production are, as indicated by the lighter tone of their skin, women, while the butchers, with their darker reddish skin, are men.” [15] Of course, the men would be more tanned, accustomed to working outdoors, and therefore they were depicted as being dark red in Egyptian art. In an accompanying color photograph, the women in the wooden model appear not to have been painted at all, where the wood is a naturally light tan or beige color.

To clarify this, in a description of a clay model of the head of a king esteemed to have been from the period of the 21st to 25th dynasties, or the 11th to the 7th centuries BC, from the same book we read: “The head has traces of dark red powdery pigment that is common on other excavated terra-cotta figurines. The color is similar to that used on the skin of male figures, perhaps to indicate that their skin has been reddened by the sun. The same color is applied to many examples of clay figurines of women, although traditionally the skin areas of statues and figurines of women was pigmented yellow.” [16] In another description of a clay figurine depicting a man and wife found in a family tomb and dated to the 25th century BC the author states in a description of the woman that “Her skin is painted a light yellow.” [17] Another figurine from the same tomb depicts two harpists, a man and a woman, but the man is depicted as a dwarf. Both male and female harpists have skin “painted the same medium yellow tone”. [18] Most of the statues or figurines of men were painted to appear dark red, but perhaps the male harpist was painted yellow since he spent far less time in the sun, only having worked indoors.

[15 Ancient Egypt, Treasures From the Collection of the Oriental Institute – University of Chicago, Emily Teeter, The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2003, pp. 35-36; 16 ibid., p. 68; 17 ibid., p. 23; 18 ibid., p.24.]

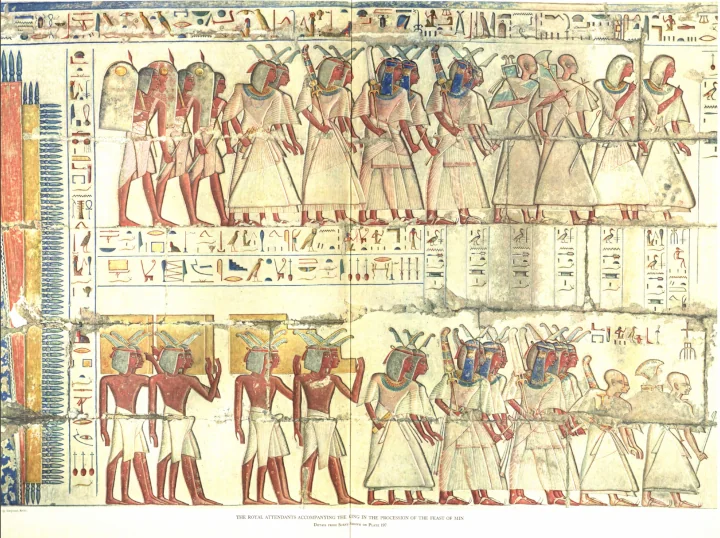

In another work co-written by the same author, we read “This distinction in gender roles is also reflected in Egyptian art. Women are shown as having light (yellow) skin, presumably because they stayed inside and out of the sun, while men are shown as having dark red skin, presumably because they were outside and subject to tanning.” [20] A similar characteristic to that of the harpist is exhibited in the contrasting appearance of priests in a painting of the royal attendants of the king, the pharaoh Ramses III, who were in attendance at a Feast of Min, as they appear in color photographs of paintings from Medinet Habu in a book titled Festival Scenes of Ramses III, a pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty who ruled Egypt during the first half of the 12th century BC. In this painting the priests are bald and their skin is white in color, while all of the other men in the painting are presented with the typical red hue of Egyptian men. However the priests would also usually work indoors. [21]

[20 The Life of Meresamun. A Temple Singer in Ancient Egypt, Emily Teeter and Janet H. Johnson, The Oriental Institute Museum Publications, Number 29, The University of Chicago, 2009, p. 83; 21 Festival Scenes of Ramses III, Medinet Habu Volume IV, John A. Wilson and Thomas G. Allen, The University of Chicago Press, 1940, Plate 197.]

Egyptian women also had long hair which fell below the shoulders. From an artifact called the “Stela of the Household of Senbu” described in Ancient Egypt and esteemed to belong to the late 12th or early 13th dynasty, spanning the 18th and early 17th centuries BC, there is a description of women portrayed in engravings and we read: “The women are dressed in long tight-fitting dresses. Nine of the ten wear long hair (or wigs) whose tresses fall over the shoulder. The female servant wears her hair in a high ponytail, a style associated with servant girls.” [22] But this also represents a problem with Egyptian art. The men often, but not always, shaved their heads, and sometimes wore wigs. The women also sometimes shaved their heads or cut their hair short, and wore wigs.

It is quite possible that Egypt had a much larger number of blondes and redheads than the art suggests, because the practice of shaving the head and the wearing of wigs by both men and women was common, at least on the special occasions which are portrayed in their art, and the wigs in art seem to have always been black. While much of the ancient Egyptian art is rather crude, a group of statues found in the late 5th Dynasty tomb of Nen-Khefet-Ka and his wife Nefer-Shemes, in which his wife is embracing him from the side, portray a couple with decidedly Caucasian features. Many other such early statues exist, where on most of them the color is lost. Strangely, most internet websites discussing these statues found in this tomb display only another statue of the couple, where the noses are broken. [23]

But Egyptian wigs were not always black. At the British Museum there is a wig on display which was excavated in ancient Thebes in upper (southern) Egypt. It is esteemed to have been from the 18th Dynasty, from the 16th to the beginning of the 13th centuries BC. The wig is a double layer of two wigs, and references to such wigs are found in inscriptions. The underneath layer of the wig is comprised of black hairs, some with apparently reddish or blondish highlights, which are braided and said to be naturally curly. The top layer of the wig is comprised of naturally blond hair which is said to have been artificially curled. The existence of this wig indicates that wigs were ceremonial, and they were not representative of the actual appearance of the wearer or his or her natural hair. [24] So where black wigs appear in Egyptian art, the natural hair of the wearer was not necessarily black. The wigs were evidently only worn for special occasions, and it is special occasions which the paintings represent.

More revealing than any of these pigments used in ancient Egyptian painting, however, are the words of ancient Egyptians. A document esteemed to be the world’s oldest medical treatise, called The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, dates to as early as the 12th Dynasty, or about the 19th century BC. [25] In James Henry Breasted’s voluminous descriptions of this ancient Egyptian treatise, there are references to faces and bodies which are pale or ruddy, and much discussion concerning the interpretations of the corresponding Egyptian words. In the Special Introduction to the work, we read in part, of a particular case described in the papyrus: “The color of the patient’s face, or of a wound or swelling, is frequently mentioned as a datum observed, e.g., ruddiness of the face (Case 7, III 10); paleness of the face (Case 7, IV 4).” [26] Within the text of the surgical papyrus, multiple examinations and treatments of this particular patient had been recorded, and later, in the description of the case itself, where Breasted explains the second examination we read in part: “In these second alternative symptoms the patient displays paleness, as contrasted with the first alternative symptoms in which he is hot, perspiring and flushed.” These changes in color and the general language used throughout the treatise to describe them are indicative of a White patient, and certainly not a dark Arab or especially a Negro.

As a digression, in The Book of the Dead, the Egyptian god Horus is described variously as having either green or blue eyes. [27]

[22 Ancient Egypt, Emily Teeter, p.39; 23 ibid., p. 27; 24 Wig, Museum number EA2560, The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA2560, accessed June 22nd, 2023; 25 The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, James Henry Breasted, Volume One, The University of Chicago Press, 1930, p. 593 ff; 26 ibid., p.40; 27 The Book of the Dead or Going Forth By Day, translated by Thomas George Allen, University of Chicago Press, 1974, pp. 43, 44, 89, 99.]

The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, which is now called the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, published most of the books which we have thus far cited for this presentation. In the 1920’s and 30’s they published a series of voluminous reports on the archaeological discoveries at Medinet Habu, a site on the west bank of the Nile River in the Theban Hills. Here several intact ancient buildings were discovered, including the 490-foot long Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III, a 20th Dynasty pharaoh who ruled in the 12th century BC, and a Temple of Amun esteemed to have been built in the 15th century BC by the 18th Dynasty pharaohs Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. [28] Among the Medinet Habu Reports published by the Oriental Institute are I The Epigraphic Survey, and II The Architectural Survey, published together in a single volume in 1931.

In the first report, in a survey of the battle scenes depicted in the artwork which was preserved at Medinet Habu, in the historic context of the 12th century BC [29] in regard to a painting of “Native and Foreign Troops in the Service of Egypt”, as it is called, we read the following: “The upper register shows native Egyptian troops in the conventional military garb of the period. The details of dress and shields are partly preserved in paint. The points of the lances are yellow, possibly representing gilded bronze. As these figures presumably stand for the royal bodyguard, their accouterment would naturally be more sumptuous than that of ordinary troops. The skirts of the uniforms are apparently semitransparent, as the artist has indicated in paint (a light pink) the backs of the thighs appearing through the cloth. In the second register, besides the trumpeter, come first three Sherden in Egyptian military garb but with the round shields of their native equipment. The Sherden certainly, and possibly the other foreigners in this register, are represented with short black beards. Their helmets are gold with copper (green) horns. The body color of the Sherden is the vermilion usual for peoples of the farther North, but that of the South Palestinians to the right [of the Sherden] is salmon. These later carry the throw stick of the Asiatic and two lances apiece. Only once at Medinet Habu do Egyptians carry two lances; but the Palestinians from the South wherever represented at the temple carry two, the Sherden do so once and the Philistines once. In the lowest register it is interesting to note how the artist has avoided obscuring the face of the foremost negro by tucking his companion’s club under his chin.” [30]

The Sherden may be associated with the coasts of Palestine and with the island of Sardinia, where inscriptions have been discovered containing their name in Hebrew-Phoenician characters. We would assert that the name, she’ar daniy, means remnant of Dan, and gave the island of Sardinia its name. The author apparently counts the Philistines as South Palestinians here. The nature of this work of art and the author’s commentary are very informative, because it is characteristic of many other ancient Egyptian paintings. The Egyptians are painted dark red, and the Sherden, or Saridinans who were esteemed by the Egyptians to be from the North were painted vermilion, which is a reddish hue that is darker than salmon, or the pinkish color in which the South Palestinians were painted. What is notable is that all of these hues are of a reddish color, and represent the colors which a White man turns when his bare body is exposed to sunlight in varying degrees of time and intensity. The negros in Egyptian paintings are almost always colored dark brown to black, but here their color was not even mentioned so it must have been unnecessary.

[28 Medinet Habu, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medinet_Habu, accessed June 22nd, 2023; 29 Medinet Habu Reports, I The Epigraphic Survey, 1928-31, by Harold H. Nelson, II The Architectural Survey, 1929/30, by Uvo Hölscher, edited by James Henry Breasted, The University of Chicago Press, May, 1931, p. 1; 30 ibid., p. 5.]

Here we can assert that the Egyptians were White, and that they saw themselves just like the others of the White nations which adjoined the Mediterranean Sea, as White and sunburned. Perhaps the darker red with which they painted themselves was a boast of their masculinity beyond their neighbors, since the more effeminate Egyptian men who worked indoors were painted in the lighter colors usually reserved for women. This is further evident in Biblical literature, where Moses himself, who would have been considered a Syrian, could pass for an Egyptian, as we may read in Exodus chapter 2: “16 Now the priest of Midian had seven daughters: and they came and drew water, and filled the troughs to water their father's flock. 17 And the shepherds came and drove them away: but Moses stood up and helped them, and watered their flock. 18 And when they came to Reuel their father, he said, How is it that ye are come so soon to day? 19 And they said, An Egyptian delivered us out of the hand of the shepherds, and also drew water enough for us, and watered the flock. 20 And he said unto his daughters, And where is he? why is it that ye have left the man? call him, that he may eat bread. 21 And Moses was content to dwell with the man: and he gave Moses Zipporah his daughter. 22 And she bare him a son, and he called his name Gershom: for he said, I have been a stranger in a strange land.” [31] Much later in history, in Acts chapter 21, a Roman military tribune had mistaken another Palestinian, Paul of Tarsus, for an Egyptian. [32] Moses, being a Semite, was taken for being an Egyptian, something that may not have happened if the Egyptians were not a homogeneous race.

[31 Exodus 2:16-22; 32 Acts 21:37-38.]

Moving on from Mizraim, or Egypt, to the town of Ugarit on the northern coast of Palestine, while this land was at a later time the land of the Amorites, it is difficult to identify the original inhabitants of Ugarit with any particular tribe. Ugarit is mentioned in tablets found at Ebla, which are esteemed to date to as old as the beginning of the 18th century BC, and Egyptian relics have been found there which date to an even earlier period, from which contact seems to have been maintained with Egypt as early as the 20th century BC. Ugarit was destroyed by the end of the 12th century BC. [33] The destruction of Ugarit preceded the taking of the coast as far north as Hamath by the Israelites from the time of the rule of David.

A tablet containing a work titled The Legend of King Keret, which is from Ugarit and esteemed to date to the early 14th century BC contains six columns of writing inscribed during the time of a king named Niqmadd, so the legend is believed to be at least semi-historical. In the legend, Keret sees his house destroyed, mostly by war and disease, and all his sons are dead. In a vision in a dream Keret sees El, the Hebrew and Canaanite word for god, elu or ilu in Assyrian, who is then called “The Father of Man”, the word for man being from a word corresponding to the Hebrew word adam. The word adam was evidently also an Akkadian word. In Assyrian, the word adamu is blood, and also a nobleman, and adamû, or edamû, is also a priest. [34, 35] In the legend, El offers Keret silver, gold and slaves, but Keret responds with a plea that he has no need for silver and gold, and requests that the god:

“Give me Lady Hurriya,

The fair, thy first-begotten;

Whose fairness is like Anath’s fairness,

Whose beauty is like Ashtoreth’s beauty;

Whose eyeballs are the pureness of lapis,

Whose pupils the gleam of jet;”

Let me bask in the brightness of her eyes;”

In the subsequent verses, El, the “Father of Man”, granted the wish and Keret had a child with the lady, but then he awoke to find that it was all just a dream. So after he awoke he washed and made sacrifices of a lamb and a turtledove to “Bull, his father El”, and then it is said that he “Honored Baal with his sacrifice.” [36] The correlations with the Israelite worship of the golden calf in the desert, and later in Dan and Bethel, are quite evident. Furthermore, here Baal is directly associated with a bull, and that also leaves us to wonder whether the word baal is the actual source for the English word bull.

But what is notable here is the description of the lady, who is idealized in the legend, as having had eyes of “the pureness of lapis”, which is a reference to a mineral called lapis lazuli. According to Geology.com, “Lapis lazuli, also known simply as ‘lapis,’ is a blue metamorphic rock that has been used by people as a gemstone, sculpting material, pigment, and ornamental material for thousands of years.” [37] This is the material which was also used for eyes in the ancient statues of Eshnunna in Mesopotamia.

[33 Ugarit, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ugarit, accessed June 22nd, 2023; 34 The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, published by the Oriental Institute in 1964, in Volume 1, p. 95; 35 ibid., in Volume 4 first published in 1958, p. 22; 36 Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, pp. 142-144; 37 What is Lapis Lazuli?, Geology.com, https://geology.com/gemstones/lapis-lazuli/, accessed June 15th, 2023.]

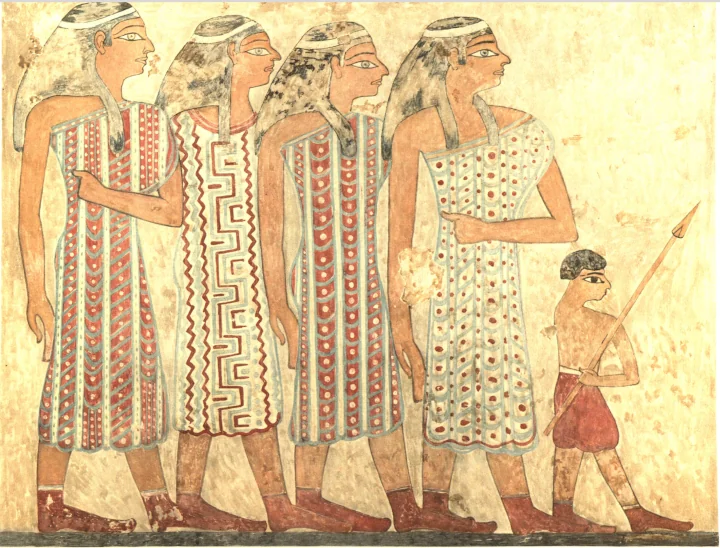

Speaking of Canaanites, in a three-volume series of books titled Ancient Egyptian Paintings there are photographs of paintings which are said by archaeologists to portray Semites which were found in the tomb of Khnemhotpe, an Egyptian official who is approximately dated to the time of the pharaohs Amenemmes (or Amenemhat) II or Sesostris (or Senusret) II, about 1920-1900 BC. The photographs are in Plates X and XI of Volume 1, but the descriptions of the paintings are in volume 3. There we read in a description of the painting titled “Semite Women” that “These women belong, as the inscription accompanying the scene tells us, to a party of ‘thirty-seven Aamu-people’ who ‘came bringing eye-paint’ to the prince Khnemhotpe. Their appearance proclaims their Semitic origin, and their home may have been in the south of Palestine. Only fifteen are actually shown, including the prince Ebsha and the children; the man and the donkey in Plate XI immediately follow the women. These have curious bird-like faces with very hooked noses and light eyes. Their irises, unlike those of the Egyptians, are light grey outlined in black, and show a small black pupil similar to those of the Syrians in Plate XLII….” A young boy accompanying the women and carrying a spear has large brown eyes. The women are very light-skinned and have gray eyes with somewhat aquiline noses, however the description given seems to have exaggerated the features. The man in Plate 11 has brown hair and large brown eyes like the boy. [38]

It is not certain that the Egyptian phrase Aamu-people refers specifically to Amorites, or to Asiatics in general. In the early 20th century BC, it is also not certain how many Semites were in southern Palestine, although that origin for these so-called Semites is also conjecture on behalf of the author. The people portrayed may have been either Canaanites or from some branch of the Semites. But as the Jews typically and improperly classify Canaanites and other Hamites as Semites simply because of their Akkadian dialects, the author is certainly also confused between the two groups.

However in Akkad, as well as in Assyria and throughout the Near East, by the dawn of the second millennium BC there must have already been intermingling between the Shemites, Hamites and Canaanites, at least in the urban centers and regions which had changed hands between conquering and vanquished tribes. But what is significant here is that light-skinned people with blue or grey eyes are apparent in two sources which are almost certainly depicting Canaanites or Canaanite ideals: The Legend of King Keret and this painting of these so-called “Semetic Women”. If the Canaanites were White, as they are depicted here, and if the Egyptians were White, then all of the descendants of Ham must have been White.

[38 Ancient Egyptian Paintings, Selected, Copied and Described by Nina M. Davies with the Editorial Assistance of Alan H. Gardiner, University of Chicago Press, 1936, Volume I, Plates X and XI, and Volume 3, pp.24-26.]

Concerning Cush, or Ethiopia, in our presentation on The Hamites we have already discussed the descriptions of apparently White Ethiopians in Africa, and the savage black tribes which also dwelt there, as they are found in the writings of Diodorus Siculus, and we have already discussed the legend of Memnon the Ethiopian, and the identification of Memnon with the city Susa, which was the capital city of Elam and later a capital city of the Persian empire. So, because Susa was associated with the “Ethiopians of the East”, as they were called by Herodotus, it is fitting to discuss Elam, or Persia, as Elam was the principle tribe of that empire and Susa was the capital city of Elam.

In Greek art, marble sculptures were usually painted in bright colors, but the color of most sculptures has faded over the centuries to the point of having been lost. A few years ago, in 2007, the Harvard Art Museum produced an exhibition based on scientific research conducted at the university and elsewhere, which resulted in color restoration for many ancient Greek works of art. The exhibition was named Gods in Color. But the results were not politically correct, as Greeks and Persians were represented as having had skin so white that it is typically found only in European countries today, and mostly in the north. A color restoration of the “Alexander Sarcophagus”, as it is called, contains a battle scene between Macedonians and Persians. The sarcophagus was actually made for the burial of Abdalonimus, who was made king of Sidon by Alexander the Great in 332, but who himself had died around 320 BC, and it contained images of Alexander the Great, hence the name. The Macedonian soldiers, fighting naked, had White but sun-burned bodies which were somewhat pink or slightly reddish, and the only visible hairs were distinctly red head and pubic hairs. The Persians, depicted as being fully dressed, the visible parts of their skin were as white as modern paper.

But the original Gods in Color exhibition catalog was quite different from the catalog which is now presented by the museum. The new catalog published at the Harvard Art Museum has very few color exhibitions, the Alexander Sarcophagus, and some other objects which had their colors restored are now wanting from the exhibition catalog, and three portraits of common arabs from Egypt have been added so that brown people could be included. Of 110 objects in the exhibition, only one has its color fully restored, and another partially restored. The three Egyptian portraits, which are of commoners rather than gods, are all from the late Roman period, they required no restoration and many other marble sculptures remain unrestored, or restoration efforts are very limited in scope. In the name of political correctness, Harvard turned its own exhibit into a pathetic joke. [39, 40]

But the original Gods in Color exhibition catalog was quite different from the catalog which is now presented by the museum. The new catalog published at the Harvard Art Museum has very few color exhibitions, the Alexander Sarcophagus, and some other objects which had their colors restored are now wanting from the exhibition catalog, and three portraits of common arabs from Egypt have been added so that brown people could be included. Of 110 objects in the exhibition, only one has its color fully restored, and another partially restored. The three Egyptian portraits, which are of commoners rather than gods, are all from the late Roman period, they required no restoration and many other marble sculptures remain unrestored, or restoration efforts are very limited in scope. In the name of political correctness, Harvard turned its own exhibit into a pathetic joke. [39, 40]

[39 Gods in Color, Harvard Art Museum /system/files/resources/Harvard%20gods%20in%20color%20gallery%20guide.pdf, original catalog hosted at Christogenea.org, accessed June 22nd, 2023; 40 Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity, Harvard Art Museums, https://harvardartmuseums.org/exhibitions/3418/gods-in-color-painted-sculpture-of-classical-antiquity, accessed June 22nd, 2023.]

However descriptions of Persians in Greek Classical and Hellenistic writings agree with the restoration of the Alexander Sarcophagus of the original Gods in Color exhibition. For example, the Greek historian Xenophon, who had direct experience in the field as a general fighting at various times both with and against Persian soldiers, which he had chronicled in his book Anabasis, wrote the following in Book 3 of his Hellenica, expressing the contempt which the Spartans had for the comparatively effeminate Persians: “And again, believing that to feel contempt for one's enemies infuses a certain courage for the fight, Agesilaus gave orders to his heralds that the barbarians who were captured by the Greek raiding parties should be exposed for sale naked. Thus the soldiers, seeing that these men were white-skinned because they never were without their clothing, and soft and unused to toil because they always rode in carriages, came to the conclusion that the war would be in no way different from having to fight with women.” [41] The same difference between Greeks and Persians is evident in the restoration of the Alexander Sarcophagus which is no longer visible at the Harvard Art Museum.

The Spartans were Dorian Greeks, and their loathing of the Persians is in spite of the fact that in Greek literature, even after the failed Persian invasion of Greece, the Dorians were considered to be a race which was kindred to the Persians. An example of this is found in the writings of the 5th century BC tragic poet Aeschylus, who actually wrote around the time as the Persian war with the Greeks, and in one of his plays he put the following words into the mouth of Atossa, the mother of Xerxes the king of Persia:

I have been haunted by a multitude of dreams at night since the time when my son, having despatched his army, departed with intent to lay waste the land of the Ionians. But never yet have I beheld so distinct a vision as that of the last night. This I will describe to you.

I dreamed that two women in beautiful clothes, one in Persian garb, the other in Dorian attire, appeared before my eyes; both far more striking in stature than are the women of our time, flawless in beauty, sisters of the same family. As for the lands in which they dwelt, to one had been assigned by lot the land of Hellas, to the other that of the barbarians…. [42]

[41 Hellenica, Xenophon, 3.4.19; 42 The Persians, Euripides, lines 76-87.]

Aside from customs such as those which made the skin of Spartans reddish or tanned and kept the skin of Persians white, the relative racial homogeneity of the Near East is evident in other ways, if one digs deeply into the ancient literature. For example, as we have said before, the Greek geographer Strabo of Cappadocia had explained in Book 16 of his Geography that the Cappadocians “have to the present time been called ‘White Syrians’, as though some Syrians were black”, and with that statement we may deduce that all the Syrians known to Strabo were white so far as he was concerned [43]. Strabo had mentioned this same subject earlier in his work, in Book 12, where he said in part, referring to a particular statement which had been made by Herodotus, that “by ‘Syrians,’ however, he means the ‘Cappadocians,’ and in fact they are still to-day called ‘White Syrians,” while those outside the Taurus are called ‘Syrians.’” The Taurus is a mountain chain in south-western Anatolia and those outside of it would apparently be to the south and east of it. There he continues and says “As compared with those this side of the Taurus, those outside have a tanned complexion, while those this side do not, and for this reason received the appellation ‘white.’” [44] The nature of the tanned complexion of Levantine Syrians is debatable, as to whether it was cultural or because the Syrians were already mixed arabs, however there is no doubt, and it is expressed even in the New Testament, that at least some “Syro-Phoenicians” were Canaanites, as the apostle Mark had called a woman who was identified as a Canaanite by the apostle Matthew. [45, 46] This event occurred less than a decade after Strabo had died, and the world of Strabo was already well-mingled, as it had become throughout the Middle East during the Hellenistic period.

But speaking of the relative racial homogeneity of the peoples further north are Strabo’s remarks in Book 12 of his Geography concerning the Cauconians, a people of central Anatolia who are mentioned as early as Homer’s Iliad. There he states in part that “As for the Cauconians, who, according to report, took up their abode on the sea-coast next to the Mariandyni and extended as far as the Parthenius River, with Tieium as their city, some say that they were Scythians, others that they were a certain people of the Macedonians, and others that they were a certain people of the Pelasgians. But I have already spoken of these people in another place.” [47] These would be the same Macedonians who were depicted with sunburned white skin and red hair in the Greek art which we have already discussed, and if a people can be confused for Macedonians, Scythians and Pelasgians, then all four groups must have been very similar in that regard. Where Strabo said that he had already spoken of the Cauconians, he refers to Book 8 of his Geography, where he attributes to them a Greek origin. [48]

Strabo made some interesting observations in Book 1 of his Geography, where he stated in part “For the nation of the Armenians and that of the Syrians and Arabians betray a close affinity, not only in their language, but in their mode of life and in their bodily build, and particularly wherever they live as close neighbours. Mesopotamia, which is inhabited by these three nations, gives proof of this, for in the case of these nations the similarity is particularly noticeable. And if, comparing the differences of latitude, there does exist a greater difference between the northern and the southern people of Mesopotamia than between these two peoples and the Syrians in the centre, still the common characteristics prevail.” [49] Here it is evident that the lines distinguishing Arabs, Syrians and others had slowly been blurring for some time before Strabo. But then in that same place he mentions another group of peoples as being similar to one another, “the Assyrians, the Arians, and the Aramaeans”, and here he distinguishes Aramaeans from Syrians, while in other places he explained that the Syrians were formerly called Aramaeans. [50] However the truth is that, as we have seen at length here, other tribes had inhabited large portions of what was later called Syria, and especially tribes of the Canaanites.

In any event, there were still Assyrians in Strabo’s time, and the Arians to the east of Persia were themselves primarily of the Persians, Medes, Parthians and other Scythians. In his account of the soldiers of various nations who had invaded Greece with the Persians under Xerxes, the more ancient historian Herodotus had explained that “The Medes had exactly the same equipment as the Persians; and indeed the dress common to both is not so much Persian as Median… These Medes were called anciently by all people Arians…” [51] Then further on, speaking of the Arians, he wrote in part that “The Arians carried Median bows, but in other respects were equipped like the Bactrians.” [52] Of the Bactrians, Herodotus wrote that they “went to the war wearing a head-dress very like the Median, but armed with bows of cane…” and then he described the Amyrgian Scythians in company with them, as they were grouped by the name of their Persian commanders. [53] Here we see similarities in cultures and tools which we would expect to find amongst related and not too distantly-situated peoples. So where Strabo explains that there was an affinity between Arians, Aramaeans and Assyrians, it reflects historical truths which can be verified in more ancient history, even if it is often only in vague sketches.

But as for Strabo’s remarks that there were similarities between Armenians and the people of southern Mesopotamia, Syrians and Arabs, even in the time of Xenophon, Chaldaeans were found in at least parts of Armenia, of whom he had written that “The Chaldaeans were said to be an independent and valiant people” [54] and later he explained that they were among a group of tribes who were not subject to the king of Persia, and who were “exceedingly formidable”. [55] So among the Armenians, where there were also certainly Israelites of the Assyrian deportations who were later known as Scythians, were Chaldaeans who were also related to the people of southern Mesopotamia. Unfortunately, however, Strabo provided no detailed physical descriptions.

[43 Geography, Strabo, 16.1.2; 44 ibid., 12.3.9; 45 Mark 7:26; 46 Matthew 15:22; 47 Geography, Strabo, 12.3.5; 48 ibid., 8.3.3; 49 ibid., 1.2.34; 50 ibid.; 51 The Histories, Herodotus, 7.62; 52 ibid., 7.66; 53 ibid., 7.64 54 Anabasis, Xenophon, 4.3.4-5; 55 ibid., 5.5.17.]

The references to White or Caucasian features in ancient Greek literature where the Greeks describe themselves, their heroes, or their gods, are far too numerous to recount. Golden-haired Menelaus [56], golden-haired Demeter [57], golden-haired Polynieces [58], golden-haired Ganymedes [59], white-armed and bright-tressed Selene [60], golden-haired Meleager [61], white-armed Persephone [62], rosy-armed Eunice and rosy-armed Hipponoë [63]. These are only a few examples from the writings of Hesiod and the Homeric Hymns. Many other epithets like them such as “Medea with the snow-white neck” [64], white-armed Hera, blue or gray-eyed Athena, the “pale white throat” and “yellow tresses” of Iphigeneia, and many more are found throughout the writings of the early Greek poets, and were continued throughout the Classical and Hellenistic periods.

[56 Hesiod, Homeric Hymns, Epic Cycle, Homerica, translated by H. G. Evelyn-White for the Loeb Classical Library, volume 57, Harvard University Press, 1914-2000, p.191, Catalogues of Women and Eoiae, 67; 57 ibid., p. 311, To Demeter, line 302; 58 ibid., p. 485, The Thebaid, 2; 59 ibid., p. 421, To Aphrodite, line 202; 60 ibid., p. 461, To Selene, lines 17-18; ibid. p. 615; 62 ibid., p. 145, Theogony, line 913; 63 ibid., pp. 97-98, Theogony, lines 246, 251; 64 Medea, Euripides, line 30.]

As for the earliest Athenian art, which is typically found as paintings on what are called Black-figure Pottery, much like the Egyptian men were always portrayed in dark red color, the Greek men in these pottery paintings are always portrayed as black, and women are always portrayed as white, ostensibly to reflect the roles of each gender in society. But even women who transcended those roles, such as the warrior goddess Athena, are painted in white. [65] As we saw in the Alexander Sarcophagus and other marble statues of which the color has been restored, the Athenians and their idols which have also been restored in that manner appear just as these many epithets in Classical writings have described them.

[65 Black-figure pottery, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-figure_pottery, accessed June 23rd, 2023. ]

So the Assyrians, according to Strabo, were akin in appearance to the Arians, who were related to the Medes and Persians, and there we see nations of both Shem and Japheth who were similar in appearance, shared many of the same customs, and who all must have been as White as the Persians of Greek art. In an oracular dream concerning the last significant Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, we read in part a testimony that the goddess Ishtar had told him, “Your face (need) not become pale, nor your feet become exhausted, nor your strength come to nought in the onslaught of battle.” [66] So once again we see language natural to White societies. The idiom of a face turning pale from fear appears on other occasions in Assyrian literature. [67]

[66 Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, p. 451; 67 ibid., p. 509, 606.]

Then there are the White Syrians who looked just like Scythians and Macedonian, Pelasgian and Cauconian Greeks, as Strabo had also attested. Then the Japhethite Ionians, of whom were the Athenian Greeks, were also White, and the White Dorian Greeks were also related to the White Persians, the Shemites of Elam. If we had time, it would not be difficult to demonstrate the fact that the Thracians of the Black Sea area and Tartessians of Iberia, who were both of Japheth, as well as the Lydian descendants of Lud the son of Shem, were also White, and the Classical literature and art also demonstrate that.

For this presentation, I did not go into the area of DNA research, mostly because such research is often based on false premises, the first of which is that modern populations are products of the ancient population of any particular region. That is simply not true. But sometimes, DNA studies admit that. For example, a 2017 article published in the Nature Communications journal and on the internet is titled Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods, and of course that is absolutely true with the rise of Islam and the arabization of the entire Near East and north Africa as well as parts of southern Europe in the 7th century AD. But the article title alone also suggests another truth, that there was Sub-Saharan African ancestry in Egypt before the Roman period, and that is also historical, as Egypt had already absorbed some Nubian blood, and then was overrun with Nubians in the 7th century BC.

So the authors of the study made admissions such as “We found the ancient Egyptian samples falling distinct from modern Egyptians, and closer towards Near Eastern and European samples” and a bit later “We find that ancient Egyptians are most closely related to Neolithic and Bronze Age samples in the Levant, as well as to Neolithic Anatolian and European populations. When comparing this pattern with modern Egyptians, we find that the ancient Egyptians are more closely related to all modern and ancient European populations that we tested, likely due to the additional African component in the modern population observed above.” [68] This outcome is precisely what we ourselves would have expected, although we would also warn that the study of DNA, or the rewriting of history if it conflicts with the results of such studies, can lead to all sorts of other errors.

[68 Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods, Nature Communications, https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms15694, accessed June 23rd, 2023 ]

In any event, the ancient Egyptians, as well as all of the sons of Noah, were White. Of this we have no doubt. When we return, we may add to this discussion, since even with this we have only scratched the surface of the available literature in this field. However with this we are also intent on continuing with Genesis chapter 11.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.