From Yahshua to Jesus: the Evolution of a Name

From Yahshua to Jesus: the Evolution of a Name

In the early years of my Christian Identity studies, I became acquainted with a plethora of wild ideas, and I actually did evaluate them all as best as I could. Some of these came from British Israel writers, and others from more recent Americans such as Rand, Swift or Comparet, and even more recent writers who are still alive today. So with an open mind and with Scripture as my guide, along with various lexicons and many books of classical history and ancient inscriptions, and even many of the so-called apocryphal or pseudepigraphal books, as I studied I had considered just about everything that an Identity Christian could hear.

Among these were the Ephraim-Scepter heresy, and the Noon-to-Noon calendar day heresy, the No-Devil heresy, and all of these Clifton had written essays about before I ever had a chance, because he was also dealing with them for a long time. Both Clifton and my friend Ralph Daigle would send me all sorts of Christian Identity-related materials, and some of it I read for entertainment purposes, while other things I took more seriously. If I ever unpack the three remaining crates of notes and correspondence I had accumulated throughout those years, perhaps I will address some of the things which have merit, or at least those which seem to need further attention because the things they proposed are still in circulation.

Throughout those years, in my studies I naturally came to many conclusions which I did not have immediately, and which had long been debated in Identity Christian circles. Foremost among these were the debates concerning Two-Seedline, the origin of non-Adamic races, the identity of certain of the trees of Eden, and other important topics. Some of the conclusions which I have arrived at over the years actually took years for me to understand, and then even more years to formulate effective arguments based on the supporting evidence.

One of the “wild ideas” I was often confronted with was the claim that the name Jesus came from that of the pagan Greek deity Zeus, and that concept is still promoted in certain Christian Identity circles today. In fact, I am certain that James Wickstrom perpetuated it throughout the entire time of his ministry, in spite of the fact that he ultimately should have known better.

So about a year after Clifton had put together his paper, Which is it, “Lord” or “Yahweh”?, I sent him this essay, Yahshua to Jesus: Evolution of a Name, which – according to his archives – he had first prepared for publication in June of 2005. Ever since, we had both thought that the two papers were complimentary of one another. However I think that in my later paper had concentrated too much on the technical aspects of the languages involved in the development of the word Jesus, so I left out at least one other important aspect of the name of our Savior which Clifton had often mentioned later, and I will also discuss that here, along with some other improvements and additions to my original paper.

As a digression, in May of 2005 I had finished the first draft of my translations of Luke and Acts, and was about to begin a review of that for a final draft, which I completed in late July.

In any event, in the format in which Clifton had published these papers, because they were pamphlets they were limited to about 3,000 words at most and even then the print would be too small. Therefore it was difficult to offer a full study of many subjects with such a relatively short essay. So making this presentation, I may depart from my usual method of preserving the original and offering my own comments and criticisms. Instead, I will rewrite what sentences I think need rewriting, I will expand on certain explanations that I think need expanding, and I will also expand many of the shortcuts that were originally taken to squeeze the text into a single pamphlet, especially regarding abbreviations and references.

So in effect, this shall actually be somewhat of an update to my 2005 essay:

Yahshua to Jesus: Evolution of a Name

The purpose of this discussion is to show how the name Jesus came into existence. I am certainly not advocating that one should call upon the name of Yahshua Christ, the Redeemer of Israel, using the name Jesus, however there are serious misconceptions concerning the origin of this name which I am compelled to address.

I remember one explanation where the claim was made that the name Jesus had come from “Hail, Zeus”, which was eventually corrupted into “Hey, Zeus”, which then resulted in the modern Spanish pronunciation of the name. That might be silly, or to some, even funny, but it is also childish and patently ridiculous. First, even in the New Testament, the customary Greek word for hail or hey is χαῖρε, and in Latin it is ave like in the hymn Ave Maria, which is translated into English as Hail Mary. Christian Identity is truth, but when we espouse these essentially childish ideas then we lose all credibility even where we speak the truth.

In order to simplify the presentation here, it shall be taken for granted that the proper English representations of the names of our God are Yahweh and Yahshua, as they are transliterated from the Hebrew. I am aware of the Masoretic spellings found in Strong’s Hebrew lexicon (i.e. Yehowshua, see #3091), yet I would dispute them. The yeho- names from the Old Testament became Ἰω- (Iô-) names in the Septuagint translation, and such is not the case with this name. For more information on this topic, see the recent pamphlet from this ministry entitled Which Is It, “Lord” or “Yahweh”? Furthermore, I am not going to make lengthy quotes from lexicons here, but shall be concise or even only paraphrase them where needed in my illustrations. Yet of course I shall cite my sources.

As I had explained where I recently presented Clifton’s first paper, one problem the ancient writers had when transliterating Hebrew names into Greek was the lack of the letter “H”, or aitch, in ancient Greek. The Greeks used the symbol to represent the vowel eta, but they did not have the letter to represent the sound which is present in Hebrew, Latin and English. When a word began with a vowel or contained the letter “R”, they did have a mark which represented the sound, but except for the letter “R” they never employed it with other letters within a word to place the “H” sound in the middle of the word. So some names were written with the letter χ (chi) instead, which is a guttural “ch” in English, and Ahaz is an example. But in many other names the letter “H” was dropped.

As I had also explained presenting Clifton’s paper, Josephus, who was a priest and a Levite, had informed us in his Antiquities that the sacred name was pronounced with four vowels, by which he meant Greek vowels, and from other and Christian writers who were nearly as early we may determine that those four vowels which he had in mind were most likely ΙΑΥΕ (iota, alpha, upsilon, epsilon) , or IAUE in English, which we may naturally pronounce as Yahweh. Now that methodology at arriving at the pronunciation of the name of our God may not be perfect, but it is certainly historical, based upon histoircal evidence, and is probably the best that we can do upon introducing the name into our modern English vernacular.

Furthermore, as I also stated here and where I will now elaborate, “yeho- names from the Old Testament became Ἰω- (Iô-) names in the Septuagint translation, and such is not the case with this name.” For example, the Jehoram of the King James Version is simply Ιωραμ in the Septuagint, Jehoiakim is Ιωακιμ, and Jehoshaphat is Ιωσαφατ. But Joshua becomes Ἰησοῦς, where the ω (omega) is changed to an η (eta), and evidently may have followed some now-lost convention of ancient Hebrew.

Many in Israel Identity purport that the corruption of Yahshua into Jesus was part of some overt conspiracy by a wicked ‘church’ to somehow replace Yahweh with the Greek Zeus. These people then claim in support of this contention that Jesus (gee-zus) and Zeus (actually pronounced zooce) are sound-alike words, yet actually they don’t sound alike at all. There is no evidence that in ancient times, the first “S” in Jesus was ever pronounced like a “Z” (zee). Actually, the Hebrews, Greeks and Romans all had a letter “Z”, and could have easily used it if they so desired. Also, the Roman supreme god was not called Zeus but Jupiter (or also Jove), so for them any supposed connection is less likely. Romans always preferred their own names for the gods over the Greek names (Mars for Ares, Diana for Artemis, Mercury for Hermes, Juno for Hera, ad nauseum), and may even have been offended if they were compelled to use any form of the name of Zeus. The Romans used a similar word, deus, for god, but deus could be used as a title to address or describe any so-called god. Here I hope to demonstrate just how the name Jesus truly came into being.

Early on in my studies I sought information on how ancient Greek was pronounced. Eventually I met a man who claimed to have studied Greek in college. His name was Michael Stewart and by his appearance he was definitely Scottish, and perhaps partly British. He made a chart for me, and on the chart several of the vowels and at least a couple of diphthongs were all pronounced like the letter “E”, or in Greek, epsilon. This I rejected, and Michael found a Greek prisoner, one who looked like a Turk to me, who confirmed his chart. So I told him that he was really speaking Turkish and that I could not accept it, and I offended them both.

Ultimately, I chose to follow the pronunciation guide for ancient Greek found in the opening pages of Strong’s Greek-English lexicon, and since then I have found resources which uphold that guide, at least for the most part. However even some academics dispute aspects of how ancient Greek was pronounced, and we can never be entirely certain. But for my purposes, in all of my pronunciations I have attempted to follow Strong’s guide, and have maintained that as best as I can until this day.

But neither can we be entirely certain that the apostles themselves had followed the classical Greek pronunciations , since scholars acknowledge that there were deviances from classical Greek in the Hellenistic period, and Koine Greek was not free of differences in dialects in various regions. There is even some evidence that there was a peculiar eastern, or even Judaean dialect of Koine Greek.

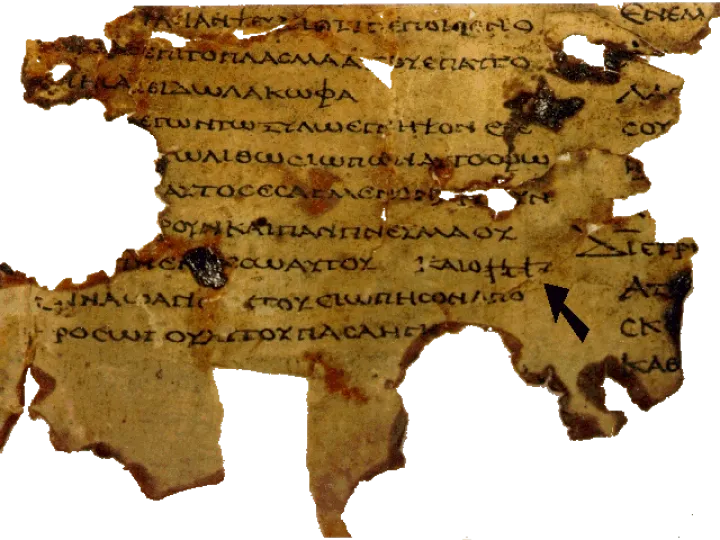

The Greek name from which Jesus is derived is Ἰησοῦς (perhaps yay-soos). Under the entry for Ἰησοῦς, the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament edited by Gerhard Friedrich explains that after the return from Babylon the early Hebrew name Yahshua was shortened to Yashua. This is the same name as Joshua of the Old Testament. In the Greek Septuagint (or LXX), a book which was translated from Hebrew into Greek long before the organized Roman Church could have made any conspiracy, wherever the name Joshua appears we find some form of the Greek equivalent, Ἰησοῦς. Of the final ς here (which in Greek is written σ if it is not the last letter of a word) the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament states “The LXX retained the later form [Yashua or Yeshua], and made it declinable by adding a Nominative ς [sigma].”

They not only made it declinable by adding the letter “S” to the end, but also by modifying the final vowels to comply with the Greek convention. The Hebrew form of Joshua ended in the letter ע (ayin) which in modern Hebrew is considered a consonant representing a rough-breathing sound, although that is certainly disputable relating to ancient Hebrew. The Phoenician form of the same letter was the origin of the Latin and Greek letter “O”, which is a vowel. Now, responding to the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament:

First, the “Nominative ς” allows one writing in Greek to decline the noun Ἰησοῦς, meaning that in that manner the word may be represented in the various Greek cases, which are, for examples: Ἰησοῦς in the Nominative case, which is typically the subject of a verb (Jesus calls); Ἰησοῦν in the Accusative case, denoting the object of a verb (“thou shalt call His name Jesus”); Ἰησοῦ in the Genitive case, which typically denotes source or possession (being of or from Jesus); and Ἰησοῖ or again Ἰησοῦ in the Dative case, which for a person denotes accompaniment or location (going with or to Jesus). Declensions are an important part of Greek grammar which are not fully utilized in English. The “’s” is an example, somewhat representing the Genitive case in our language, where for the most part we rely on word order and the use of prepositions. So adding the “S” greatly assists the Greek writer. An example of an indeclinable noun in Greek is Δαυίδ (David), which may have been declinable if it were written Δαυιδός (Davidos), although in Biblical Greek it never was.

Now, in November of 2019 while I am preparing this revised presentation of this essay, I have found that the declinable form Δαυιδός is used as a name by some modern Greek speakers, but it was not used in Scripture. Continuing my response to the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament:

Secondly, it may be apparent that the final “A” sound in Yahshua was also dropped for Greek, so that Ἰησοῦς (yay-soos) is really only equivalent to Yashu. The only place in the LXX where the sound of that final vowel was retained is the Ἰησουέ of 1 Chronicles 7:27, although some LXX versions have it in a couple of other places as well. There we see the following, speaking of the genealogy of the Old Testament Joshua: Νουμ υἱὸς αὐτοῦ Ιησουε υἱὸς αὐτοῦ.

The occurrences of Ιησουε in some manuscripts of Scripture do indeed help us to establish that the original Hebrew spelling would be more like our Yahshua than Yesu, a form I will comment on later.

In the Hebrew spelling, which has no true vowels, the -a on the end of Yahshua comes from the letter ע (‘ayin). In later Masoretic Hebrew (between 600 and 900 A.D.) vowel points were added, and in the Old Testament, the ע (‘ayin) was accompanied with vowel points signifying that it is followed by an “A” sound. While the letter “A” does not actually exist in the name, perusing the transliterations in Strong’s Hebrew dictionary along with his English spellings and pronunciations, practically everywhere that this letter appears a vowel is supplied along with it. The vowel points on the letter ש, (shiyn) indicate that it is accompanied by the letter “U”. According to the Wikipedia article for the letter ע (‘ayin), in writing it is frequently omitted in transliterations, and the “vowel quality is shifted” but it is evident that the vowels are nevertheless retained.

Now to repeat ourselves once again: Thirdly, the missing h must be addressed. In Greek, there is no letter equivalent to the letter h (Η, aitch). The symbol Η is there, but represents the uppercase vowel eta, which in lowercase is η. While in Greek there is a ch (χ, chi), a th (θ, theta) and a ph (φ, phi) neither is there an sh letter.

If there were a letter for “H” in Greek, perhaps the ע (‘ayin) may have been retained in transliteration.

The Greeks designated an aspirant (or “H” sound) before words which began with a vowel by using the symbol which we know as an apostrophe or opening single quotation mark (‘), which denotes the presence of the sound, or a reverse apostrophe or closing single quotation mark (’) which denotes its absence. But with the exception of the words which contained χ, θ and φ, there was no way by which the Greeks added such a sound in the middle of a word, although there is one other exception, which is some occurrences of the “R” sound, but that is beyond the scope of our discussion here. Furthermore, there was no way for ancient Greeks to represent an sh sound in writing.

But this was not a problem for the Hebrew speaker, since as can be seen in the “Hebrew Articulation” section of the Hebrew dictionary which accompanies Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance, in Hebrew the same letter, ש, siyn or shiyn, represent either the s or sh sound. So it would not be a problem at all for a Hebrew reader writing in Greek to see the Hebrew letter siyn or shiyn, and for the sh sound to write a Greek sigma (ς).

Therefore understanding that Ἰησοῦς is a natural transliteration into Greek of the Hebrew name which is pronounced as Yahshua is easy, once all of these conventions of the two languages are understood. So the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament observes that: “The evidence of the NT is to the same effect [as the LXX]. In Ac 7:45 and Hb 4:8 there is a reference to Ἰησοῦς, i.e. Joshua the son of Nun.”

In other words, if those passages mention Ἰησοῦς in reference to the Joshua of the Old Testament, then we know that Ἰησοῦς is how they had chosen to write the Hebrew form of Joshua in Greek. In the King James Version of Acts chapter 7 we read: “45 Which also our fathers that came after brought in with Jesus into the possession of the Gentiles, whom God drave out before the face of our fathers, unto the days of David; 46 Who found favour before God, and desired to find a tabernacle for the God of Jacob.” And of course the “Jesus” referred to in that passage is the Joshua of the Old Testament who had led the children of Israel into the land of Canaan. Then in Hebrews 4:8 there is another reference to Joshua and it says “8 For if Jesus had given them rest, then would he not afterward have spoken of another day.” So it is clearly evident, that “Jesus” is somehow a form of the Hebrew name which is transliterated as Joshua in the Old Testament. Once we realize that the “J” was originally a “Y” sound even in English, we see that the true name is Yahshua.

But this leads me to another digression. There are protests to our use of the name Yahshua, that the apostles did not write in Hebrew, but in Greek, and therefore in English only transliterations based on the Greek form of the name Ἰησοῦς are acceptable to Christians, because Christ was called Ἰησοῦς by His apostles. But this argument is also based on a false premise.

Simply because the apostles wrote in Greek does not mean that as Christ was with them that they had addressed Him by His name in Greek. Although it is certain that all of the books of the New Testament were originally written in Greek, many statements in the Gospels and the Book of Acts indicate that the apostles often spoken Hebrew, which was their primary language, regardless of whether any of them may have been able to speak Greek to one extent or another. [As another digression, today academics think they spoke Aramaic, but the apostles themselves called what they spoke Hebrew, and since they spoke it they should know better.]

Not all Judaeans could even speak Greek, and it seems that typically they did not speak Greek. In Acts chapter 21 we read of a Roman centurion’s surprise that Paul of Tarsus could speak Greek. This is found in verse 37, where Paul is being led off into the Roman fort, and Luke wrote: “And as Paul was to be led into the castle, he said unto the chief captain, May I speak unto thee? Who said, Canst thou speak Greek?” So it is very plausible that the apostles did address Christ by the Hebrew form of His name, which is Yahshua, since they spoke to Him in Hebrew. But much later, while writing the gospels and other accounts and letters found in the New Testament, they used the Greek form of the name only because they were writing in Greek.

Now, hopefully having established that Ἰησοῦς is the Greek equivalent of the Hebrew form of the name Yahshua, and sufficiently explaining how that may be so, attention may be turned to the Greek, Latin and English.

The Greek eta (Η, η) is a difficult vowel, since it has no direct equivalent in Latin or English. Although the majority of scholars usually represent it in transliterations of names with an e (or ê), there are many who more often represent it with an a. Examples of the η changing among the languages are evident in Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance, where the Hebrew word for Mede is transliterated by Strong as Maday (Hebrew #4075) and the Greek word, no different in the New Testament [Acts 2:9] than in all classical Greek, is Μῆδος (Greek #3370), which Strong transliterates Mēdŏs and pronounces it may´-dos. In Genesis 10:2, the word at Strong’s Hebrew #4074 was rendered in the King James Version as Madai. So we need not look far to see that the a and the e are both interchangeable with the Greek letter η (eta).

The letter i (iota) at the beginning of a word, when followed by a vowel, James Strong represents with a double e in all of his pronunciations in his Greek lexicon. This is correct, although for practical purposes the i becomes equivalent to the spoken English letter y in these instances, and this is true for the Latin as well, neither Greek nor Latin having a letter y as we know it. [for example, y-e-a-r is pronounced nearly identically to ee-e-a-r.]

In Greek the symbol “Υ” represented the uppercase upsilon, the lowercase υ, and the equivalent of our own u although it is transliterated most often with a y (examples being the prefixes hyper- and hypo-). In the New College Latin & English Dictionary by John C. Traupman, Ph. D. it is explained that in Latin the letter “Υ” was “adopted from the Greek into the Roman alphabet for the transliteration of words containing an upsilon (for which u was used earlier), and pronounced approximate as German ü ... but its use was restricted to foreign words.” So while the Hebrew had a y, the yowd, neither Latin nor Greek had an exact equivalent, both using an i in words where today in English we use a j, such as in Jerusalem, Joppa, or Jacob, all of which may be discerned from Strong’s Concordance.

When the Roman Latin speakers encountered the Greek Ἰησοῦς, which would have been pronounced yay-soos, or as Strong has it, ee-ay-soos, they wrote Iesus. As we have seen, the “e” is a fair representation of the Greek η (eta). Checking Strong’s Greek lexicon and the “Greek Articulation” section at its beginning, the ou diphthong in Greek is pronounced as the ou in the English word through. In the pronunciation section of the New College Latin & English Dictionary on page 4, there is no ou diphthong in Latin, yet the Latin “u” is by itself able to represent the same sound (“ū u in rude”) as the Greek ou diphthong, and so the Latin Iesus is a fair representation of the Greek Ἰησοῦς. Again checking the New College Latin & English Dictionary, the “i” in Latin would be treated no differently as it would be in Greek, “ī ee in keen”, as Strong represents it as ee where it begins a word and is followed by another vowel.

Here it must be pointed out that the pronunciation guide in the New College Latin & English Dictionary is split into two sections, the “Classical Method”, and the “Ecclesiastical Method” which became extant among the clergy in the Medieval period. At the letter s under “Classical Method” it states “always s in sing”, but under “Ecclesiastical Method” it states “s in sing... but when standing between two vowels or when final and preceded by a voiced consonant = z in dozen.” So we see that in the Latin of the later Church, Iesus began to be pronounced yay-zus, yet bear in mind that this change affected a large number of Latin words, and not just this one name.

This leaves us with the English letter “J”. According to the table entitled “Development of the Alphabet” on p. XXXIV in the opening pages of The American Heritage College Dictionary, third edition, the “J” appeared in the miniscule script which was prevalent from 300-700 A.D., and the Carolingian script from circa 800 A.D., along with later scripts. But of our language The American Heritage College Dictionary states that “The English alphabet reached its total of 26 letters only after medieval scribes added w (originally written uu) and Renaissance printers separated the variant pairs i/j and u/v.” And so we see that in English, “J” became a distinct letter only during the Renaissance, which began in the 14th century, and that the letter “J” was only a variant of the letter “I”.

However, just because in some European scripts we have a “J” at an early time, that does not mean that the letter was pronounced then as we pronounce it today, as we do the soft g (i.e. gentle, germane) which seems to have come from the French (where it is represented by a zh in pronunciations of French words which appear in The American Heritage College Dictionary), although I have by no means fully researched the matter. The Spanish pronounce the “J” as an English “H”. In the pronunciation guide to the New College Latin & English Dictionary on page 5 we find that the “J” of Medieval (and Ecclesiastical) Latin (for The American Heritage College Dictionary attests that Classical Rome did not know the letter) was pronounced like the “y in yes.” Even closer to our language is German, which pronounces the “J” as a “Y”, and so Jesus in German would sound much the same as it did in Latin, or in Greek, Iesus.

Checking The American Heritage College Dictionary for the pronunciation of the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung’s last name, we find yoong, and the Swiss city Jungfrau is yoong-frou. A Junker, a member of the old Prussian aristocracy, is a yoong-ker. (In all three cases the oo is said to be pronounced as the oo in our word took.) In The American Heritage College Dictionary the name of the sea bird called a jaeger, named from the German word for hunter, is pronounced ya-ger. It is common knowledge that the popular German name Johann, our John, is pronounced yo-hann. The Greek spelling is Ἰωάννες (Iôannes).

While it is beyond the purpose of this document, it must suffice to say that, in spite of the insistences of both Jews and Arabs to the contrary, the Gospels were originally written in Greek. While a form of Hebrew (which some academics insist was Aramaic) was spoken in first century Palestine, Greek was also a common language there, as the historical and archaeological records also attest. The internal evidence, both textually and contextually, leaves no doubt in the mind of the Greek reader that such was the language they were written in. And so it should be evident that some form of Ἰησοῦς was the name which Yahshua Christ was called by and responded to during His walk upon this earth.

Originally I had written this to address the people who would connect the name Jesus to Zeus. While it is still true, today I am more persuaded that the form of Ἰησοῦς by which Christ was more frequently addressed is the Hebrew form, Yahshua, although that cannot be proven conclusively. I am persuaded that in writing the apostles always used the Greek form, as they were writing in Greek, but that while they knew Him in this world, it is more plausible that they addressed Him by the native Hebrew form, which was their first language.

In any event, here it should be manifest that Jesus, or the Latin Iesus, evolved naturally from the Greek form Ἰησοῦς, having suffered several incremental alterations with changes in language and dialect, and so Jesus is not a name produced by some conspiracy, although it should be kept in mind that Ἰησοῦς, Iesus and Jesus were all originally pronounced yay-soos (or yay-sooce), or at least something quite similar. Stripping away the final s, added for the benefit of the Greek (and later Latin) grammar, all of these versions may be represented by the simple Yesu, a form known to Identity scholars in the 19th century, evidenced in the work of E. O. Gordon (Prehistoric London) and others. As we have seen, Yesu is only a Hellenized form of the Hebrew Yahshua, without the final a.

Although I first read it very early in my studies, I would like to read it again one day, where I can now be more critical. In chapter 1 of his book Prehistoric London, Gordon wrote of Druidism from the Welsh, or ancient British perspective and he said: “The universe is infinite, being the body of the being who out of himself evolved or created it, and now pervades and rules it, as the mind of a man does his body. The essence of this being is pure, mental, light, and therefore he is called Du-w, Duw [in Welsh] (the one without darkness). His real name is an ineffable mystery, and so also is his nature. To the human mind, though not in himself, he necessarily represents a triple aspect in relation to the past, present and future; the creator as to the past, the saviour or conserver as to the present, the renovator or re-creator as to the future. In the re-creator the idea of the destroyer was also involved. This was the Druidic Trinity, the three aspects of which were known as Beli, Taran, Esu or Yesu. When Christianity preached Jesus as God, it preached the most familiar name of its own deity to Druidism; and in the ancient British tongue ‘Jesus’ (‘Saviour’) has never assumed its Greek, Latin or Hebrew form, but remains the pure Druidic, ‘Yesu.’” So this is what I had recalled when I wrote that last paragraph in 2005, but I can also remember seeing the term in other British-Israel literature.

While I would now say that we cannot know very much concerning Druidism, it is evident that at least many of the British people accepted Christianity as early as the first century, long before the Romans, and that in some places, vestiges of the early Keltic church remained independent of Rome until the 13th century, when even then they were forced into the Roman Church by an English king.

The name Ἰησοῦς appears both in the New Testament and in the works of Flavius Josephus as a personal name for many men other than Yahshua Christ, and therefore it must have been a given name which was somewhat popular around that time. But the Jews seem to have always despised the original form and corrupted it.

It is evident in many places that the modern Jews, who never were true Hebrews or Israelites, prefer the spelling Yeshua, and in recent times it is a common name among them. Although the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament states that “With the 2nd century A.D.... Ἰησοῦς disappears as a proper name”, it seems to have revived since the founding of the artificial zionist state in Palestine. I feel quite safe in stating that even in Christian Identity circles, a writer who uses the form Yeshua has been heavily influenced by Jewish literature, and his work should be viewed in that context, for it may well be suspect. Non-Judaized Israel Identity writers generally use the form Yahshua.

The word Yeshua in Hebrew (ישוע) is spelled one Hebrew letter short of Yahshua (יהושע) and it can mean “He Saves”, but that can indicate any man who saves, when in truth it is only Yahweh God who can save man. Using that form, as we shall see, actually turns a prophecy about the Hebrew form of the name Joshua into a lie, which is found in Exodus 23:21. It is another Jewish rabbit-hole by which they avoid the Name of Yahweh with a more secular replacement.

There is another myth among Identity Christians, that Yeshua really means “May his name and memory be blotted out”, but that is not true. Rather, there is an anagram that Talmudic Rabbis had allegedly made and which is said to be found in the Talmud, and the anagram is made from the Hebrew letters of the shortened form of the name Yeshua, however the name Yeshua does not bear that meaning by itself.

While I cannot disparage forms such as Jesus or Yesu, knowing how those forms came to be, yet in my own writings I use the form Yahshua, and I believe that I have good reason for so doing. First, in English there are not the limitations in pronunciation or spelling which the Greek language had imposed, which made the form Iesus necessary in the first place. Secondly, the form Yahshua represents a meaning which is absent in Jesus, its component parts being derived from the words Yahweh (that name which the Jews both despise and avoid, cursing all who do mention it), and a form of a word meaning salvation or to be saved. So Yahshua conveys a meaning which is not evident in the other forms: Yahweh, Savior or Yahweh Saves, a statement which is descriptive of the very purpose of Yahshua Christ in the first place, and also of His very essence.

Clifton had often pointed out an important prophecy in this regard, which in the immediate sense refers to Joshua the son of Nun, but which in the prophetic sense is indeed a reference to Yahshua Christ. This is found in Exodus chapter 23: “20 Behold, I send an Angel before thee, to keep thee in the way, and to bring thee into the place which I have prepared. 21 Beware of him, and obey his voice, provoke him not; for he will not pardon your transgressions: for my name is in him. 22 But if thou shalt indeed obey his voice, and do all that I speak; then I will be an enemy unto thine enemies, and an adversary unto thine adversaries.”

So where Yahweh had said of Joshua the son of Nun that “My Name is in Him”, and Yahshua Christ had that same name in its Hebrew form, we know that the Name of Yahweh is also in His Name, and that He should be called Yahshua. The prophecy may also be interpreted to refer to Christ, and Yahweh’s Name is in Him, so it must be Yahshua. For this same reason we read in Matthew chapter 1 where the angel speaks to Joseph instructing him to accept the pregnant Mary and says “21 And she shall bring forth a son, and thou shalt call his name JESUS, (or Ἰησοῦς): for he shall save his people from their sins.” Many take this to refer to the form of the name which means “he saves”, however in Isaiah chapter 45 we read “21 Tell ye, and bring them near; yea, let them take counsel together: who hath declared this from ancient time? who hath told it from that time? have not I the Yahweh? and there is no God else beside me; a just God and a Saviour; there is none beside me. 22 Look unto me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth: for I am God, and there is none else.” Yahweh saves, and there is no other. So in Isaiah chapter 49 we read “26… all flesh shall know that I Yahweh am thy Saviour and thy Redeemer, the mighty One of Jacob.” Being the Word made flesh, being Yahweh God incarnate, Yahshua Christ certainly fits the description of the statement made by His Name, which is Yahweh saves. Any other form of the word loses the significance of its true meaning.

This ends my presentation From Yahshua to Jesus: the Evolution of a Name.

Now I am going to offer an addendum to my last presentation, which is Clifton Emahiser’s short essay titled Just Because the Term “Ya” was Found at Ebla & Ugarit is no Sign that Yahweh is Canaanite in Origin!

It is fitting to do this here because it answers some of the questions of those who had scoffed at his first paper. Clifton evidently published this later essay in May of 2007, ostensibly in response to certain Identity Christians who were following Pete Peters, who was insisting that Christians use the name Jesus exclusively in reference to Christ. So he begins:

The “Jesus only” people are busy in an attempt to prop-up their faulty premise that the names “Yahweh” and “Yahshua” have a Canaanite origin. Check any good dictionary or encyclopedia and one will find that the letter “J” never existed in any language before the Middle Ages. It was the Medieval scribes that began the usage in the 1600s. While “J” is the 10th letter of the English alphabet, it was the last letter (or 24th) to be added by the scribes. Therefore, if “Jesus” is the correct name, the English “J” must be dropped (or pronounced “esus”). Neither Paul nor any of Christ’s disciples ever used the term “Jesus” with an English “J”! And, because there is no equivalent in the Greek for the English letter “J”, no early New Testament writer ever wrote the name “Jesus”. That brings up another question: Because the Greek alphabet has both a long and a short “e” ((1) epsilon & (2) eta), which of these two “e’s” do we use? Surely these experts on the name “Jesus” should be able to explain this! So, that leaves us with only the letters (“sus”) to enunciate His Name. And what kind of a name is that? It sounds a little like a hissing snake!

Clifton is being sarcastic, but it demonstrates that any insistence on an adherence to a particular transliteration of a word is simply wrong when there are two or more plausible transliterations. But a transliteration based on letters which have only come into existence since the original word was used, representing sounds which never existed in that original language, is certainly wrong, since it cannot represent the sound of the original word. So he continues:

It is coming through the grapevine that these “Jesus only” people are going to try to prove that the name Yahweh can be found in Ugaritic texts, and that that somehow makes the Tetragrammaton to be of Canaanite origin. These “Jesus only” people simply detest the names Yahweh and Yahshua. Even the King James translators became confused with the name Yahshua at Hebrews 4:8. If you have an older KJV you will find it reads: “For if Jesus had given them rest, then would he not afterward have spoken of another day.” The reason that the KJV translators became confused was because both Christ (the Anointed One) and Joshua of the 6th book of the Old Testament have the same name. If you have a Revised Standard Version, and check this verse, it reads: “For if Joshua had given them rest, God would not speak later about another day.” Well, which is it, Jesus or Joshua? Again, let all of the “Jesus only” people explain this one also!

The KJV translators also made this same mistake at Acts 7:45! The KJV reads: “Which also our fathers that came after brought in with Jesus into the possession of the Gentiles, whom God drave out before the face of our fathers, unto the days of David.” The RSV reads: “Our fathers in turn brought it in with Joshua when they dispossessed the nations that God thrust out before our ancestors. So it was there until the days of David.” Again, I ask, which is it, Jesus or Joshua? I could quote from many commentaries that understand that both Christ and Joshua have the same name. And, once we understand there was no English “J” in either Hebrew or Greek, Joshua can only be properly pronounced with a “Y” sound. Therefore, any man that gets up before his audience and denounces the name of Yahshua, and then turns around and quotes from the book of Joshua is a blathering idiot!

I know that Pete Peters did this often, however I do not know if Clifton had anyone else in mind. A few years ago, Clifton had me publish an article he wrote criticizing one of Peters’ Dragonslayer newsletters which contained an article condemning the use of the Hebrew name of God and disparaging anyone who used it. Peters wrote that article in 2009, and by 2011 he was dead after a riding accident, at the relatively young age of 63. Continuing with Clifton:

For anyone who pretends to understand the Ugaritic texts, needs to get the three-volume Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language edited by Cyrus H. Gordon and Gary A. Rendsburg. The archaeological finds of Ebla predate Abraham by several hundreds of years. It was like finding some lost historic data from Noah to Abraham. As of this date, no older texts relating to Scripture have been found. In volume 2, there is a chapter entitled “Ebla and the Gods of Canaan”, written by Robert R. Stiegliz pp. 79-89, and the name Yahweh is not mentioned once as one of them, nor is it even hinted at! My hope is, with this thesis, I can head Pete Peters off at the pass. On page 79 Stiegliz says:

“… Ebla is thus situated midway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Euphrates River, in a region which was long the meeting ground of diverse peoples: Canaanites, Amorites, Hurrians, Akkadians, and Sumerians.” Of course, the Sumerians were Aryans as attested by Waddell in his The Makers Of Civilization and Egyptian Civilization with too many references for all of them to be mentioned here. In his The Makers Of Civilization on page 86 is a subtitle “The Advent of the ‘Sumerians’ into Mesopotamia & its Date About 3335 B.C.” Surely the Sumerians where Shemites and would have been familiar with the Divine Name.

The year 3335 BC is roughly around the time of Noah’s flood according to chronologies based on the Septuagint, which are much more accurate than the Jewish Masoretic Text. But I do not agree that the Sumerians were Shemites. In fact, there is strong evidence of a previous “fallen angel” civilization there, but then in Genesis chapter 10 we read of Nimrod that “ 10 And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar.” The giant Gilgamesh once ruled over Erech. Babel and Shinar were in the land known as Sumer, and Nimrod came out of Ham, although Akkad was later the land of the Shemitic Assyrians. So the races and nations were already mixed up at that early time. Clifton continues:

As for the Canaanites, Amorites, and Hurrians, it would somewhat parallel Genesis 15:19-21. I wrote about the Ebla find in my Watchman’s Teaching Letter #30 thusly:

THE EBLA FIND

As I promised you last month, I will bring you information on an archaeological find at a place known as Ebla. I will now quote from The Thompson Chain-Reference Bible, the “Archaeological Supplement” in part, pages 1791-1793. As this archaeology supplement is being continually updated by Thompson, your edition may read differently than what I am quoting here:

“ ... The most impressive of these mounds [discovered at Ebla] is known as Tell Mardikh, which lies some 30 miles south of modern Aleppo, rises 50 feet above the plain, and covers an area of 140 acres ... In the spring of 1964 Dr. Paolo Matthiae, professor of Near East archaeology at the University of Rome, obtained a permit to excavate Tell Mardikh with his wife, Gabriela, and an efficient archaeological team of assistants.

“During the first few years they carried out soundings in various parts of the mound. Uncovered were city gates similar to those of Solomon at Gezer and Megiddo, and two small chapel-type temples like the famous temples of Shechem, Megiddo and Hazor — all dating between 2000 and 1600 years before Christ, the period called Middle Bronze I and II.

“In 1968 the archaeologists discovered a royal statue which bore a dedicatory inscription to one Ibbit-Lim, ‘Lord of the City of Ebla, to the goddess Ishtar.’ It soon became clear that they were excavating the remarkable metropolis of the kingdom of Ebla, an immense Semitic empire whose center was set on the plains of modern Syria. From occasional references to it in ancient inscriptions — from Ur, Lagash, Nippur, Mari, and Egypt — archaeologists had long suspected the presence of such a civilization in North Syria. Many places and events of history would now fall into proper place.

“In 1973 work was begun in Early Bronze Age Ebla, which dated between 2400 and 2225 B.C. Excavators found a tablet indicating the city at this period was divided into two sections — an acropolis (high city) and a lower city. The acropolis contained four building complexes: the palace of the city, the palace of the king, the palace of the servants, and the stables. The lower city was divided into four quarters, each of which had a gate: the gate of the City, the gate of Dagan, the gate of Rasap, and the gate of Sipis.

“In 1975, while excavating in the palace of the city, the chief administrative center, they came upon the ruins of a large three-story royal palace building which had flourished four generations before the birth of Abraham. It contained a spacious audience court (100 to 170 feet, with a portico of carved wooden and stone columns adorned with gold and lapis lazuli), a tower room, and smaller rooms at the entrance of the courtyard. In the tower room were 42 cuneiform business tablets and a small school exercise tablet.

“During the following year they worked in the two rooms at the entrance of the courtyard. In the first room were about 1,000 business and administrative tablets, which were found ‘rather spread out and disordered.’ The second room was a large library — the authentic royal archives — containing 15,000 tablets that had been regularly arranged on wooden shelves. When the palace was destroyed by fire, however, the flames devoured the wooden shelves, and the tablets settled on top of one another ...

“In a nearby room were another 1,000 tablets, along with writing implements. This they took to be the scribe’s room. In yet another room were 800 tablets, along with beautifully carved wooden figures, seal impressions, and plaques of wood, gold, and lapis lazuli. One sheet of gold was found ... Professor Pettinato found that the major portion of the tablets were written in Sumerian wedge-shaped cuneiform script – the world’s oldest written language. The tablets themselves, however, dated from the middle of the third millennium B.C. One large tablet was a dictionary giving the Sumerian equivalents of some 3,000 Eblaite words. With the help of this lexicon, Pettinato was able to dicipher [sic] many other Eblaite tablets. About 20 percent of the tablets were written in a northwestern Semitic language which Pettinato called Paleo-Canaanite, or Old Canaanite, although the script used was also cuneiform Sumerian. This he says, was the language spoken in Ebla and is closer in vocabulary and grammar to biblical Hebrew than any other Canaanite dialect, including Ugaritic.”

Pettinato’s label is unfortunate, as even by his own words, he should never have called proto-Hebrew by the label proto-Canaanite. First, Ugaritic is not necessarily Canaanite, and is more likely Phoenician. Eblaite is certainly an early language from which Hebrew was eventually derived. Second, there were Hebrews other than Israelites, and other related peoples who must have spoken similar languages to Hebrew or Aramaic, who were also not Canaanites. Ebla also lies in the area of Padan-Aram, which means the Plain of Aram, which was the home of the kindred of Abraham. Continuing with Clifton’s citation:

“Contents and Significance of the Tablets”

“The tablets so far unearthed number nearly 20,000, the majority of them large. Those which have been translated — only a fraction of the total — tell of the economy, administration, education, religion, trade, and conquest of a great commercial empire of which all memory had been lost in the historical traditions of the Near East.

“ ... what they have found already throws a flood of light on so many aspects of research in the field of ancient history and biblical archaeology that in many quarters the Ebla Tablets are now considered more significant for elucidating ancient history and the early backgrounds of the Bible than any other archaeological discovery ever unearthed.

“With its empire, the city of Ebla, whose population is given in one tablet as 260,000, constituted one of the greatest powers in the Ancient Near East during the third millennium B.C. Its commercial and political influence extended far beyond its own borders – from Sinai in the southwest to Mesopotamia in the east. As a major trade center, it controlled east-west commercial routes for grain and livestock from the west, cedar timber from Lebanon, and metals and textiles from Anatolia – the home of the Hittites – along with trade in silver and gold and the several other commodities from Cyprus and other Mediterranean countries.

“Ebla was a flourishing Semitic civilization. Her arts prospered and her craftsmen were renowned for the quality of their metal work, textiles, ceramics and woodworkings. They made cloth of scarlet and gold, weapons of bronze, and furniture of wood. Their educational system was far advanced. They kept records in their own language on tablets of clay which they stored in archives deep in the cellars of the royal palace.’ All this existed more than a thousand years before the brilliant civilization of David and Solomon.

“Ebla had a king and a queen. Like Israel, it anointed its kings and had prophets. The king was in charge of state affairs, and his queen was held in equally high regard. The crown prince helped with domestic and administrative affairs, while the second son aided his father in foreign affairs. The tablets are quite explicit about the structure of the state and about the royal dynasty. Six kings are listed, among which is Ebrum. The resemblance of his name to Eber, the father of the Semites, according to Genesis 10:21, is astonishing, since it is virtually the same name as the biblical Eber, a direct descendant of Noah and the great-great-great-great-grandfather of Abraham.

Yet Eber, for whom the Hebrews were named, is only a portion of the race of the Shemites, which was actually named for Shem and not Eber.

“Other names found in these texts and later used by biblical characters are: Abraham, Esau, Saul, Michael, David, Israel and Ish-ma-il (Ishmael).

“The gods worshipped at Ebla numbered around 500, and included El and Ya. El is a shortened form of Elohim, used later by the Hebrews and in the Ugaritic tablets. Ya is a shortened form of what some think might be Yahweh, or Jehovah, and was used for their supreme god and gods in general. Other principal gods were Dagan, Rasap (Resef), Sipis (Samis), Astar, Adad, Kamis, Milik ...

This does not disturb me, that a supreme God named Ya is mentioned in the inscriptions of Ebla, an apparently Shemitic city. So in my presentation of Which Is It, "Lord" Or "Yahweh"?, I said the following:

It is apparent that Abraham was raised in a pagan environment, as the Scriptures also inform us that his fathers were pagans, where we read in Joshua chapter 24: “2 And Joshua said unto all the people, Thus saith the LORD God of Israel, Your fathers dwelt on the other side of the flood [river Euphrates] in old time, even Terah, the father of Abraham, and the father of Nachor: and they served other gods.”

Then in Exodus chapter 3 we read: “13 And Moses said unto God, Behold, when I come unto the children of Israel, and shall say unto them, The God of your fathers hath sent me unto you; and they shall say to me, What is his name? what shall I say unto them? 14 And God said unto Moses, I AM THAT I AM: and he said, Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel, I AM hath sent me unto you. 15 And God said moreover unto Moses, Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel, The LORD God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, hath sent me unto you: this is my name for ever, and this is my memorial unto all generations.” And in Exodus chapter 6: “3 And I appeared unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and unto Jacob, by the name of God Almighty, but by my name YAHWEH was I not known to them.”

All of this shows that the name Yahweh was not known to Abraham, Isaac or Jacob, but it does not mean that the name was unknown in even more ancient times. I would assert that because the name was apparently derived from a dialect more ancient than Hebrew but from which Hebrew had developed, that alone is an indication to us that it was at one time known to the ancients. Forms of it appear in inscriptions from Ebla that predate the time of Moses, and it also appears in inscriptions found at Ugarit. While I am not convinced, and even reject the notion that the Ugarit texts predate Moses, even if they do it would only indicate that the name was known in more ancient times, as the texts from Ebla may also indicate. None of this disturbs a faith in Scripture, as men much more ancient than Moses must have possessed the truth of that same God who had made covenants with Noah and Adam, but as the Scripture attests, from the time of Moses Yahweh revealed Himself only to the children of Israel.

Once again continuing with Clifton’s citation:

“In recording the trade and treaty dealings of Ebla, the tablets give the names of hundreds of individual place-names, among which are Urusalim (Jerusalem), Geza, Lachish, Joppa, Ashtaroth, Dor, and Megiddo, as well as cities east of the Jordan. One tablet (No. 1860) mentions the cities of the plain – in the same order as in Genesis 14:2 (Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboiim, and Bela, or Zoar) – as being cities with which Ebla carried on extensive trade. This was the first time these place-names had been found outside the Bible. Dr. David Noel Freedmen had pointed out that this record precedes the great catastrophe involving Lot which many modern scholars have regarded as entirely fictional.

This was a very important discovery which proves the story of Lot and the destruction of Sodom, Gomorrah, and those other cities. Clifton’s citation continues, but we must bear in mind that where the writer says “Canaanite”, the label is not true:

“The texts contain Canaanite [actually Shemite] stories of the Creation and the Flood and a Canaanite [actually Shemite] code of law. The creation tablet — a beautifully inscribed ten-line poem — is closer to the Genesis account than anything else discovered. In essence a part of it reads:

“‘There was a time when there was no heaven, and Lugal (‘the great one’) formed it out of nothing; there was no earth, and Lugal made it; there was no light, and he made it.’

“The Flood story is given in five columns on a small tablet ... Ebla is only partially excavated, yet a part of the royal palace, two temples, a fortress, three city gates and tablets which now number nearly 20,000 have been exposed ... At one time Ebla even ruled over and collected tribute from Mari. Reverses came, however, and ancient Ebla was destroyed. Apparently the destruction was incomplete, for Ebla enjoyed something of a second life during the early part of the second millennium B.C. ... Around 1800 B.C. Ebla became a vassal state of the great kingdom of Aleppo, spoken of in the Mari letters as Yamhad. Around 1600 B.C. Naram-Sin, king of Akkad, defeated Ebla in battle and destroyed the city. From this disaster the city of Ebla never recovered, and it remained buried under its own debris until modern excavators began to resurrect it ...”

Clifton A. Emahiser

Now that ends Clifton’s portion of his brief paper, where he did not say much in response, but instead he added an addendum which I probably wrote for him after I proofread the first part. So here it is:

Addendum By William Finck

Ebla and Ugarit were two different places. Ugarit was on the coast of northern Syria, at the site of the modern Ra’s Shamrah (near Latakia, modern Al Lādhīqīyah). Ebla was closer to the modern Halab, ancient Aleppo, 100 miles NE of Ugarit. Another 100 miles NE of Aleppo is Harran, which I shall discuss below. It should be pointed out that the finds at Ebla are much older than the finds at Ugarit, and examining them helps us to place the finds at Ugarit in a more proper historical context. It should also be pointed out – as I have said in my Phoenicians essay – that the Canaanites are NOT Shemites, as the archaeologists so often erroneously suppose, and that early forms of the Hebrew language are NOT “proto-Canaanite”! Therefore it should further be pointed out that, just because the early inhabitants of both Ebla and Ugarit kept their records in, and apparently spoke, an early form of Hebrew, that does not make them Canaanite!

The lands where Harran and Ebla, and perhaps even Ugarit, were located are the ancient Padan-Aram, the home of Abraham’s kin and of Jacob’s father-in-law, Laban the Syrian (see Gen. 12:4-5; 25:20; 27:43; 28:2-7; 48:7 et al.). The people who occupied these lands were clearly NOT Canaanites, at least at this early time. Rather they were Abraham’s kin, Hebrews and Aramaeans, and these were the ancient lands of Arphaxad and Aram, who were brothers. That “Ya” was the chief God of the pantheon of Ebla indeed shows that the people there may once have had the truth, but fell into a state of idolatry, and were subsequently judged: the same pattern seen in the empires of more recent history. Just because Abraham himself had not known our God by the name Yahweh (i.e. Exod. 6:3) does not mean that his ancestors didn’t know the name. Rather, it is apparent from the Ebla finds, as well as other sources, that at one time they did know it.

So it is evident that 12 years ago, I had the same opinion in this regard that I expressed a little more fully last week while discussing this topic, which I have already also repeated here. Continuing with my remarks:

The Thompson article cited above shows that names such as Abraham, Esau, Saul, etc. were used in Ebla in the third millennium B.C., a thousand years before Moses. Why wouldn’t the children of Israel continue to use names which their ancestors prior to Abraham had used? The Daniel mentioned by the prophet Ezekiel (14:14, 20; 28:3) is not necessarily his contemporary, Daniel the prophet. For instance, another Daniel, who lived much earlier, was mentioned in “The Tale of Aqhat”, a story dating to before 1300 B.C., [which was] found at Ugarit! (Ancient Near Eastern Texts, pp. 149-155).

The name of the God “El”, and personal names which end in the letters -ya and begin in Ya-, a god named “Yabamat Liimmim”, Baal, Anath (Athena!), etc. all appear in the Ugaritic texts reproduced in ANET. “El” is called the “Creator of Creatures”, and there are many parallels here with the myths and legends of Greeks, Hebrews, Sumerians and Akkadians. Yet the people of Ugarit were not necessarily Canaanites, and even if they were, Canaan also had Noah for an ancestor, and would have grown up with and shared those same traditions found in the other branches of the race. The Canaanites were not quarantined. Surely much of their culture would be common with that of various Adamic families. It would be infantile to think differently. Yet Ugarit lies in lands never considered in ancient times to belong to Canaan, which lay far to the south, bordering near Sidon. Ugarit lies in the neighborhood of Aram, and its occupants, who spoke a dialect similar to Hebrew, which the descendants of Aram also spoke, certainly needn’t have been Canaanites, and in all probability they were not. There is much imagery in the legends of Ugarit which leads me to believe that they certainly were not Canaanites, and a much more thorough study of their archaic literature is needed by all.

One tablet from the Baal legend of Ugarit says at its end: “Written by Elimelech the Shabnite. Dictated by Attani-puruleni, Chief of Priests, Chief of (Temple)- herdsmen. Donated by Niqmadd, King of Ugarit, Master of Yargub, Lord of Tharumeni.” (ANET, p.141). Another describes a “Lady Hurriya … Whose eyeballs are the pureness of lapis” (ANET, p. 144), and lapis-lazuli was blue. In another place, Tyre and Sidon and their idols Asherah and Elath are mentioned (ANET, p. 145). Yet if these tablets are correctly dated to the 13th c. B.C., Phoenician Israelites may have produced them, yet these mentions are not an indication of the authors by themselves. Further study of these legends are essential to determine their entire significance.

Observing the more accurate chronology of the Septuagint, there are roughly 1,300 years between the time of the flood and the call of Abraham, years which we know very little about. Indeed, the Bible is practically silent concerning these years, for which it offers us nothing more than Genesis chapters 9, 10 and 11. 1,300 years of discrepancy between the Masoretic text and the Septuagint text would put us today at approximately at 7,300 years rather than 6,000 years after Adam. Why don’t these “Jesus only” people address this time discrepancy issue?

I think that last line belonged to Clifton, as it sounds like something he would write, but we were discussing Septuagint chronology often at that time.

In any event, and I do not want to sound obnoxious because Pete Peters did die after breaking his leg after a riding accident. But I still must say that when he disparaged the original Hebrew names of our God Yahweh and Yahshua His Christ, that he did not have a leg to stand on.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.