The Jews in Europe: John Dee and the Kabbalah, Part 2

The Jews in Europe: John Dee and the Kabbalah, Part 2

Here we are going to continue to present some aspects of the life of John Dee as they were recorded in a biography of the English alchemist, mathematician, and mystic. Our primary source is the biography of John Dee which was written by Charlotte Fell Smith and published in 1909. By the time we are finished, we hope to establish that John Dee was an advocate of the Jewish Kabbalah, through which he had introduced Jewish mysticism into the intellectual circles of 16th century England, just as Johann Reuchlin had done in Germany a few decades earlier. As we also hope to illustrate, the impact this would have on history cannot be overstated.

The year is 1583, and the Polish Prince Laski is in England. A French ambassador of the time speculated that Laski was in England to persuade the Muscovy Company to stop selling arms to the Russians. He certainly did not go merely to see John Dee. But Laski was also an alchemist, and very interested in John Dee, whom he insisted on meeting and being entertained by quite frequently almost as soon as he had arrived in London. Charlotte Fell Smith basically dismisses the idea that John Dee was a spy. In chapter 13 of her biography (pp. 168-169) she says “Dee's letters to Walsingham, with their veiled allusions to secret affairs, form one of the grounds upon which the supposition has been based that he was employed by the Queen's minister as a secret spy and diplomatic agent abroad, and that his kabbalistic diagrams contained a cipher. An elaborate theory was constructed to support this contention.” However, when considering the possibility that in his later trips abroad John Dee was acting as a spy for the English court, we must remember that the Queen herself had financed Dee’s ability to entertain Prince Laski and his entourage. So Elizabeth seemed to have encouraged Dee’s developing a relationship with Laski. But the financing did not endure. It must also be noted, that in her biography Charlotte Fell Smith had several times already described Dee’s troubles securing his diaries in a household replete with servants and fellow-workers. Those fellow-workers, namely his scryer Edward Kelley, had often caused Dee troubles, and therefore if Dee were a spy, he had every reason not to include the information in his biography. So while we do not accept much of the conjecture of the conspiracy theorists, we cannot rule out the possibility that Elizabeth encouraged Dee’s travels abroad so that he may report back to her any information he may gather. However on the other hand, Elizabeth being a long-time friend and patron of John Dee, that well-known relationship which he had with the English queen must have preceded him, and it would only have been natural for him to report to her anything which he had seen abroad.

One underlying thread in all of this which must be mentioned is Dee’s relationship with Edward Kelley, his long time partner and scryer. While we will only give a brief summary. Smith describes at great length the tumultuous relations between the men, and the extent of Kelley’s dishonesty. Evidently, Dee was very naive and trusted Kelley, who was only using Dee as a vehicle whereby to enrich himself. Smith also describes how Kelley had used his scrying, his communications with the spirits of the netherworld, to his advantage in that endeavor. From this point there are many tales of visions and conversations with spirits, or demons, which are evidently woven into the narrative from Dee’s own diaries and other biographical materials. They must be waded through in order to sift out any relative historical information, and often it is difficult to separate the fantastic tales from the historical narrative. The visions and spirits, which they believed were angels, seem to have been as real to Dee and Kelley as the actual people with whom they had regular contact.

Kelley was prone to frequent outbursts of anger, where his own wife was often the victim. Of one of these outbursts, recorded by Dee, Smith says “This is the last entry in the diary before Dee's departure for Poland with Laski.” then she continues on page 116, in chapter 9 of her book:

The Prince proposed to take the whole party from Mortlake back with him to the Continent. He was reputed to be deeply in debt, and seems to have entertained wild hopes that they, aided by the spirits, would provide him with gold, and secure to him the crown of Poland. Kelley foresaw an easy and luxurious life, plenty of change and variety suited to his restless, impetuous nature. He had not as yet been out of England. There were very obvious reasons that he should quit the country now if he would escape a prison. Dee had been a great traveller, as we know, and these were not the attractions to a man of his years. He went in obedience to a supposed call, in the hope of furthering his own knowledge and the Prince's good. The notion of providing for himself and his family lay doubtless at the back of his mind also, but he had all a genius's disregard for thrift and economy, and though very precise and practical about small details, as his diary proves, his mind refused to contemplate these larger considerations of ways and means.

He disposed of the house at Mortlake to his brother-in-law, Nicholas Fromond, but in such a loose and casual way that before his return he found himself compelled to make a new agreement with him. He took no steps about appointing a receiver of the rents of his two livings, and when he came back the whole six years were owing, nor did he ever obtain the money. He says he intended at the most to be absent one year and eight months. It was more than six years before he again set foot in England.

So, unprepared, he left Mortlake about three in the afternoon of Saturday, September 21, 1583. He met the Prince by appointment on the river, and travelled up after dark to London. A certain secrecy was observed about the journey. Laski, as we have seen, was under some suspicion of Walsingham and Burleigh, whose business it had become to learn news from every Court in Europe. He was suspected of plots against the King of Poland.

In the dead of night, Dee and Laski went by wherries [either barges or rowboats] to Greenwich, "to my friend Goodman Fern, the Potter, his house, where we refreshed ourselves." Probably a man whom Dee had employed to make retorts and other vessels for his chemical work. Perhaps they met there the rest of the party, but on the whole it seems more probable that all started together from Mortlake. The exit of such a company from the riverside house must have been quite an event. At Gravesend, a "great Tylte-boat" rowed up to Fern's house, on the quay, and took them out to the two vessels arranged to convey them abroad. These ships, which Dee had hired, were lying seven or eight miles down stream — a Danish double fly-boat, in which Laski, Dee, Kelley, Mrs. Dee and Mrs. Kelley and the three children, Arthur, Katherine and Rowland Dee, embarked at sunrise on Sunday morning; and a boyer, "a pretty ship," which conveyed the Prince's men, some servants of Dee, and a couple of horses….

Sparing the details, Laski, Dee and party reached Brill eight days after leaving Mortlake, on the 29th. A few days later passing through Rotterdam, Tergowd and Haarlem they reached Amsterdam, where they stayed only three days and Dee sent one of his employees with all of his “heavy goods” by sea to Dantzig. The main party travelled through the low countries into Saxony to Embden, where Laski stopped to receive some money from the Landgrave. From there they went on to Bremen. Here Dee and Kelley are described as having communicated with some of their familiar spirits (or demons), and inquiring about the business which Laski had conducted along the way, whether or not he was successful in securing any money from the noblemen whom he had stopped to see along the route. As our author has inferred, at this time the throne of Poland had been challenged and was unstable, and Laski was one Polish prince who endeavored to have it for himself. From Bremen the party traveled to Hamburg, where Laski stayed behind, and went on to Lübeck, which they reached on December 7th.

Here Kelley had been informing Dee that the spirits had presaged riches for them, and tempted him to leave Laski behind in order to pursue them. Kelley describes a vision of eleven rich noblemen, and is portrayed as having said to Dee: “If thou enquire of me where and how, I answer, everywhere, or how thou wilt. Thou shalt forthwith become rich, and thou shalt be able to enrich kings and help such as are needy. Wast thou not born to use the commodity of this world? Were not all things made for man's use?” But Dee refused, citing an obligation to Laski. Smith wrote: “Here are the old dreams of the philosopher’s stone, the elixir of life, the transmutation of metals and all the works of alchemy, for which both these travellers were adventuring their lives in a foreign land. Dee does not seem exactly dazzled by these allurements.”

It is at this point that John Dee learns, supposedly from one of Edward Kelley’s spirits, that his brother-in-law, Nicholas Fromond, had troubles at home. Smith says:

There is no evidence that Fromond was imprisoned, but he was a poor protector of his brother-in-law's valuable effects. He was powerless against a mob who broke into Dee's house not long after his departure from Mortlake, made havoc of his priceless books and instruments, and wrought irreparable damage. It was now nearly two months since Dee had left Mortlake, and, moving from place to place, it was unlikely that he had heard any news from thence. No date has ever been assigned to this action of the mob. It is quite conceivable that it actually took place on this day, November 15, and that by Kelley's clairvoyant or telepathic power the news was communicated across the sea and continent to Dee.

And we have already mentioned that Charlotte Fell Smith herself seemed to be persuaded by or sympathetic to these occult beliefs.

After a description of Dee’s anguish and prayers in response to the news we read:

So he seeks for a revelation of guidance, writes letters to Laski, and waits. Soon he perceives these temptations to have come from "a very foolish devil." He decides that they will continue to throw in their lot with Laski, who rejoined them in Lübeck. He left again to visit the Duke of Mecklenburg, they meanwhile going by Wismar to Rostock and Stettin, which place they reached at ten o'clock on Christmas morning. Laski joined them in a fortnight. They passed on by Stayard to Posen, where Dee adds an antiquarian note that the cathedral church was founded in 1025, and that the tomb of Wenceslaus, the Christian king, is of one huge stone. It was here that Dee began to enter curious notes about Kelley in the Liber Peregrinationis, written in Greek characters, but the words are Latin words, or more frequently English. The supposition is that Kelley was unacquainted even with the Greek alphabet. Dee kept his other foreign diary, written in an Ephemerides Caelestium (printed in Venice, 1582), secret from his partner, for Kelley had obtained possession of an earlier one kept in England and had written in it unfavourable comments, as well as erased things, about himself. Dee had the last word, and has added above Kelley's "shameful lye," "This is Mr. Talbot's, his own writing in my boke, very unduely as he came by it." The various diaries sound, perhaps, confusing to the reader, but are really quite simple. By the private diary is meant the scraps in the Bodleian Almanacs, edited by Halliwell for the Camden Society, in which he seldom alludes to psychic affairs. The Book of Mysteries is the diary in which he relates all the history of the crystal gazing. The printed version (True Relation) begins with Laski's visit to Mortlake on May 28, 1583.

Here it may be evident that if John Dee is a spy, and since there is little reason to believe that Charlotte Fell Smith’s account of these travels is not accurate, then John Dee is a seemingly terrible spy. Prince Laski has visited noblemen from the ranks of Landgrave to Duke throughout Germany, and the evidence tells us that Dee himself had no thought nor interest of attending his meetings, or even remaining in close proximity. Rather, he just seems to be a curiosity along for the ride. In Winter, they then covered the distance from Stettin to Posen, and on to Lask, which Smith described as being on “the Prince’s own property”, which is the county of Lask, hence his name, Laski. Technically, Laski was a Count, and not a Prince. Lask was southwest of Lodz, and about 230 kilometers north of Krakow, which was at this time a very prosperous city and the capital city of Poland. Count Lask also held Kesmark at this time, a royal free town in Poland, or at this time in Hungary, (but now in modern Slovakia). Despite its location, Kesmark was settled by Saxon and Carpathian Germans as well as Slovaks. Both Lask and Kesmark were heavily mortgaged, and Laski was hoping on intervention from the emperor to prevent his default. Dee and his company arrived in Krakow on March 13, 1584.

Here it may be evident that if John Dee is a spy, and since there is little reason to believe that Charlotte Fell Smith’s account of these travels is not accurate, then John Dee is a seemingly terrible spy. Prince Laski has visited noblemen from the ranks of Landgrave to Duke throughout Germany, and the evidence tells us that Dee himself had no thought nor interest of attending his meetings, or even remaining in close proximity. Rather, he just seems to be a curiosity along for the ride. In Winter, they then covered the distance from Stettin to Posen, and on to Lask, which Smith described as being on “the Prince’s own property”, which is the county of Lask, hence his name, Laski. Technically, Laski was a Count, and not a Prince. Lask was southwest of Lodz, and about 230 kilometers north of Krakow, which was at this time a very prosperous city and the capital city of Poland. Count Lask also held Kesmark at this time, a royal free town in Poland, or at this time in Hungary, (but now in modern Slovakia). Despite its location, Kesmark was settled by Saxon and Carpathian Germans as well as Slovaks. Both Lask and Kesmark were heavily mortgaged, and Laski was hoping on intervention from the emperor to prevent his default. Dee and his company arrived in Krakow on March 13, 1584.

In his notes, Dee is giving dates by two calendars, the old Julian and the new Gregorian, which had been introduced in 1582. England was still using the old calendar, and continued to use it until 1742. But Poland was a Catholic country and compelled to follow the Pope. At this time, Dee himself had also attempted an improved calendar, and the book which resulted was never published. When his scheme was rejected, it was partially on the grounds that it was derived from the Romans. But Dee wanted to omit eleven days rather than ten as the Romans had. Our author notes that when the English finally modified their calendar in 1742, eleven days were omitted.

Here there is a tale of skrying, and the reception by Kelley of “cabalistic letters and signs” from angels. Kelley becomes quite disenchanted, and wants to part from Dee, for reason that after two years the spirits had never explained what the strange symbols mean. Dee tries to console him, claiming to have it all figured out, but ultimately it is the spirits themselves who convince Kelley to stay. A short time later, a familiar “angel” (demon) named Nalvage was instructing Kelley and Dee in geography. We read the following, where it is speaking initially of Kelley:

That night after the sitting, he again swore he would not go on skrying. The morning after, Dee knocked at his study door, and bade him come, for Nalvage had left off the previous day in the middle of an interesting geographical lesson about unknown parts of the earth, and had told them to be ready to continue it next morning. Kelley was obdurate, and Dee retired to prayer. In half an hour, the skryer burst in with a volume of Cornelius Agrippa's in his hand, where he said all the countries they were told about yesterday were described and written down. [Cornelius Agrippa had died in 1535. This episode shows that Dee and Kelley were familiar with his work, which we will cite later in this presentation.] "What is the use," he said, " in going on with this farce, if they tell us nothing new?" Dee replied that he was glad to see Kelley had such a book of his own; that Nalvage in giving those ninety-one new names of countries, all of seven letters, was answering his particular request; that he had verified the lands in the charts of Gerardus Mercator and Pomponius Mela, which he had at hand and produced, "and now," he said triumphantly," we know exactly what angels govern which countries, in case we are ever called to practise there…."

Now Charlotte Fell Smith seems to be oblivious, but here we witness the same desire in John Dee which Johannes Reuchlin had expressed in De Verbo Mirifico, or The Wonder-Working Word. In chapter 7 of The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit and its Impact on World History, E. Michael Jones wrote the following:

Reuchlin separated himself from the magic manuals of the Middle Ages. In place of these magic spells, which were either meaningless mumbo-jumbo or, worse, appeals to evil spirits, Reuchlin proposed the magic of the Hebrews found in the Caballah and intimately bound up with their language, the language of God Himself. Reuchlin claimed because God spoke in Hebrew, Hebrew words uttered in the proper way had an immediate physical effect. They could not bring about creation ex nihilo, but they might very well influence the angels put in charge of that creation by God. In learning Hebrew, as Reuchlin did at the feet of rabbis, the adept learned the language God Himself had used to speak to Moses. Men could now use that same language in speaking to the angels who ran the universe and create wonders by their very words.

We shall exhibit John Dee’s references to the Kabbalah further on in this discussion, which he had made in his 1564 book, Monas Hieroglyphica. However here we see that Dee could not have been getting his ideas from “the magic manuals of the Middle Ages” which Reuchlin had also forsaken. Rather, in Monas Hieroglyphica Dee refers to the “real Kabbalah”, which must have been precisely the same Kabbalah of the rabbis that Johann Reuchlin was also advancing. Dee’s ideas concerning angels and control of the universe were precisely the same objectives which Reuchlin also had. [We can only wonder why this none of this ever dawned on the original Hebrews, and that alone exposes Reuchlin as a sucker for the Jews. John Dee followed in his footsteps.]

On the 25th [of May, 1584], Laski arrived and left again for Kesmark. [One of the oldest towns in Hungary, a royal free town since 1380. It lies in the valley of the Popper, within reach of the magnificent scenery of the Hohe Tatra, a group of the Central Carpathian Mountains.] He now intended to redeem his property there. But King Stephan and his Chancellor were both set against him, and he wished Dee to go with him to the Emperor of Austria, Rudolph II.

It has been eight months since John Dee had begun his travels with Laski, and this is the first mention of his invitation to any of Laski’s visits to the courts of Europe.

Instructions were now given that they must be ready to go with Laski to the Emperor, must make themselves apt and meet, for until no remembrance of wickedness is left among them they cannot forward the Lord's expeditions. Gabriel [one of the supposed angels] tells Kelley at some length of his many faults. Dee did not hear this, but considerately does not ask for a repetition of the catalogue. He only bids Kelley listen well, Gabriel says if any will be God's minister, he must sweep his house clean, without spot. He must not let his life be a scandal to the will of the Lord.

Of the life of John Dee while he was in Krakow, little is said, except that our author notes that:

All this time, Dee is so absolutely absorbed with his spiritual visions that we know very little about his outer existence. For three years after he left England, he neglected to enter anything in his ordinary diary, and the Liber Mysticus contains nothing of everyday affairs.

She recounts only one event, where upon the sickness of his son Dee made and recorded a serious vow, and his son, who was near death, fully recovered. From there we read the following:

Still the journey to Prague to the Emperor Rudolph was postponed, and it was not until the first day of August that the trio set off. Dee and Kelley were ready to go sooner, but Laski had not sufficiently recovered his finances. The party had been augmented by the arrival of Kelley's brother, Thomas, and Edmond Hilton, son of Dee's old friend, Goodman Hilton, who had sometimes lent him money, and who in 1579 had requested leave for his two sons to resort to Dee's house. Thomas Kelley accompanied the Prince and his pair of crystal gazers. The women were left behind under Edmond Hilton's charge.

Five or six days after arriving in Prague, on the day of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, August 15, Dee was settled in the house of Dr. Hageck, by Bethlem in Old Prague (Altstadt), kindly lent him for his use. The house was not far from the old Rathhaus, the great clock tower of which, dated 1474, and the Council Chamber, still exist. It was also near the Carolinum or University, founded by Charles IV. in 1383, in whose hall John Huss a hundred and fifty years before had held his disputations. When Dee and his party arrived in the city Tycho Brahe was still alive, though not yet a resident in Prague. Prague was the city of alchemists. The sombre, melancholy Emperor himself relieved his more serious studies by experiments in alchemics and physics….

Emperor Rudolf II allegedly had at least several illegitimate children, but never married. He was eventually overthrown and usurped by his own brother, Matthias, who locked him up in the last years of his life. Matthias ruled until 1619.

Our author goes on to describe the study in the home of this Dr. Hageck which was afforded to John Dee during his stay in Prague, how it “had been since 1518 the abode of some student of alchemy, skilful of the holy stone. The name of the alchemist, ‘Simon,’ was written up in letters of gold and silver in several places in the room. Dee's eyes also fell on many cabalistic hieroglyphs...” and we don’t need to convey much more than that. Dee and Kelley quickly returned to their sorcery:

In these congenial surroundings skrying was at once resumed. Madimi (now grown into a woman) [the female ‘angel’, or demon] was the first visitor, and Dee hastened to inquire for his wife and children at Cracow. He notes that his first letter from her arrived on the 21st. She joined him before long. He was told to write to the Emperor Rudolph. He did so on August 17, and he relates in the epistle the favourable attention he has received from Charles V. and his brother Ferdinand, Rudolph's father, the Emperor Maximilian II., who accepted the dedication of his book Monas Hieroglyphica, and others of the imperial house. He signs the letter, "Humillimus et fidelissimus clientulus [Humble and faithful servant] Joannes Dee."

John Dee’s letter was sent to the emperor Rudolf via a Spanish ambassador in Prague, accompanied with a copy of Dee’s book, Monas Hieroglyphica. The same night, Dee was informed that the emperor, who himself was something of an alchemist, had graciously accepted the book and would appoint Dee “within three or four days ... a time for giving him audience.” Of the coming of the day of the appointment, our author writes:

Dee started at once to the Castle, the Palace of Prague, and waited in the guard-chamber, sending Emericus to the Lord Chamberlain, Octavius Spinola, to announce his coming.

"Spinola came to me very courteously and led me by the skirt of the gown, through the dining chamber to the Privie chamber, where the Emperor sat at a table, with a great chest and standish of silver before him, and my Monad [Heiroglyphica] and Letters by him."

Rudolph thanked Dee politely for the book (which was dedicated to his father), adding that it was "too hard for his capacity" to understand; but he encouraged the English philosopher to say on all that was in his mind. Dee recounted his life history at some length, and told how for forty years he had sought, without finding, true wisdom in books and men; how God had sent him His Light, Uriel, who for two years and a half, with other spirits, had taught him, had finished his books for him, and had brought him a stone of more value than any earthly kingdom. This angelic friend had given him a message to deliver to Rudolph. He was to bid him forsake his sins and turn to the Lord. Dee was to show him the Holy Vision.

"This my commission is from God. I feign nothing, neither am I a hypocrite, an ambitious man, or doting or dreaming in this cause. If I speak otherwise than I have just cause, I forsake my salvation," said he. Rudolph was probably very much bored by this mystical rhapsody. He excused himself from seeing the vision at this time, and said he would hear more later. He promised friendship and patronage, and Dee, who says he had told almost more than he intended of his purposes, "to the intent they might get some root or better stick in his minde," was fain to take his leave. In a few days he was informed, through the Spanish ambassador, that one Doctor Curtius, of the Privy Council, "a wise, learned, and faithful councillor,'' was to be sent to listen to him on the Emperor's behalf. Uriel, whose head had been bound of late in a black silk mourning scarf because of Kelley's misdoings, now reappeared in a wheel of fire, and announced favour to Rudolph.

"If he live righteously and follow me truly, I will hold up his house with pillars of hiacinth, and his chambers shall be full of modesty and comfort. I will bring the East wind over him as a Lady of Comfort, and she shall sit upon his castles with Triumph, and she shall sleep with joy."

To Dee, he says, has been given "the spirit of choice." Dee petitions that his understanding of that dark saying may be opened: "Dwell thou in me, O Lord, for I am frail and without thee very blind."

The conference between Dee and Curtius on September 15 lasted for six hours. It took place at the Austrian's house, whither Dee was permitted, it seems, to take the magic stone and the books of the dealings. Dee in all good faith promised that many excellent things should happen to Rudolph, if only he would listen to the voice of Uriel. Dee's sincerity, credulous though it appears, was as yet unshaken. He lived in a transcendental atmosphere, and trembled, as he believed, on the brink of a great revelation. The very heavens seemed opening to him, and soon, he thought, he would probe knowledge to its heart.

Kelley, on the other hand, was under no delusion. He had worked the spirit mystery for long enough without profit; already he was beginning to more than suspect that the game was played out; that their dreams of Laski as King of Poland, dispensing wealth and favour to his two helpers, were never to be realised; that the Emperor's favour would be equally chimerical and vain; and that some more profitable occupation had better be sought. At the back of his mind lay always the hope of the golden secret. Somehow and somewhere this last aspiration of the alchemist must be realised.

From here the lives of Dee and Kelley are filled with ominous warnings from the demons they conjured, and delusions of grandeur which was always just out of reach. John Dee nevertheless developed a friendship with this Dr. Curtius, through which was the hope of gaining the emperor’s trust and favor. However, as our author informs:

His ministers were naturally envious of this foreigner, and many whispers, as well as louder allegations against the two Englishmen, were abroad, although, as San Clemente told him, the Emperor himself was favourable. The Spanish ambassador was friendly enough, and Dee dined several times at his table. He professed to be descended from Raymond Lully, and, of course, like every educated person of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, was a believer in the virtues of the philosopher's stone. He bade them not regard the Dutchmen's ill tongues, "who can hardly brook any stranger." Dee wrote again to the Emperor a letter of elaborate compliment and praise of vestrae sacrae Caesareae Majestatis [Your Imperial Majesty], in which he offered to come and show him the philosopher's stone and the magic crystal.

Still nothing came of it, and these needy adventurers in a foreign land began to get into deadly straits. "Now were we all brought to great penury: not able without the Lord Laski's, or some heavenly help, to sustain our state any longer." Dee returned from a dinner at the Spanish ambassador's to find Kelley resolved to throw up the whole business and start for England the next day, going first to Cracow to pick up his wife. If she will not go he must set off without her, but go he will. He will sell his clothes and go to Hamburg, and so to England. It is all very well for the spirits to promise spiritual covenants and blessings; but as Kelley said to Uriel, "When will you give us meat, drink and cloathing ?"

Dee’s skryer and long time assistant, Kelley, was quite dejected but he did not return to England at this time. Rather, their wives and children with the rest of their party had arrived in Prague from Cracow some time before September 27th, 1584, so far as our author can tell from John Dee’s diary. This is important to our perception of John Dee. If the primary purpose of this journey by Dee and Kelley was to function as spies for Elizabeth, then one may imagine that they would have clung to Count Laski in Cracow, and perhaps they would have received financial replenishment from England. Instead, when Laski’s fortunes did not turn out as expected, they readily relocated to Prague, attempting to gain the favor of the emperor. That would bring them patronage and repair their financial woes. We must remember that things did not turn out as expected for Laski either, since he had hopes to be made king of Poland at a time when the throne was being contested, and he was also heavily in debt. Apparently Laski encouraged Dee and Kelley to come to Cracow with him in the first place, as good-luck charms who would assist his success merely by their presence, and while that position is indeed quite naive Laski had that same confidence in conjured spirits that Dee and Kelley professed. As it appears from Dee’s diaries, Laski did support Dee and Kelley to some degree later on, as he seems to have been a sincere lover of John Dee’s work, and the records show that Laski and Dee were in contact at least until 1593. Laski lived until 1604.

In spite of the spirits, who produced more lies than truths – such as a prophecy that emperor Rudolph would be succeeded by his brother Ernest, which never happened, Dee’s fortunes seemed to hinge on his friendship with Dr. Curtius. In this light, Smith continues her account:

But on September 27 Dr. Curtius called to see him at his lodging in Dr. Hageck's house by Bethlem, and he says, "saluted my wife and little Katherine, my daughter." [The street is still called Bethlehems Gasse. It runs from the Huss Strasse to the embankment on the Moldau.] Dee laid before him some of the slanders that he knew were going about. He had been called at Clemente's table a bankrupt alchemist, a conjuror and necromantist, who had sold his own goods and given the proceeds to Laski, whom he had beguiled, and now he was going to fawn upon the Emperor. Curtius was at last induced to spread before the Emperor his report of the conference he had held (by [Rudolph’s] command) with Dee. "Rudolph," said Curtius, "thinks the things you have told him almost either incredible or impossible. He wants you to show him the books." Then the talk became the learned gossip of a couple of bookish and erudite scholars. [During which the pair seem to have strengthened their friendship.]

After this Smith describes the troubles related to the birth of the fourth of John Dee’s eight children (six of which survived to adulthood), and then picks up the account of Dee and Curtius:

Curtius and Dee became good friends. The Austrian showed his English acquaintance several of his inventions connected with the quadrant and with astronomical tables, and Dee confided to him the secret of a battering glass he had contrived for taking observations on a dark night. The glass was left at Cracow with his books and other goods, but he would gladly go and fetch it to show the Emperor. This led to Dee's request for a passport to enable him to travel, with servants, wife and children, where he would in the Emperor's dominions at any time within a year. He drew it up himself on October 8, 1584, and the Emperor granted it without demur. Dee soon started for Cracow to bring the rest of his goods to Prague, but the diary for the month of November is missing, and the following book opens on December 10, when he had set out from Cracow to return to Prague. "Master Kelley" was with him, John Crocker, and Rowland and his nurse, who had been left behind when Mrs. Dee and the two elder children joined her husband in Prague. As before, more than a week was occupied with the journey, which was made in a coach, with horses bought of "Master Frizer." In Prague a new lodging was found in a house belonging to two sisters, of whom one was married to Mr. Christopher Christian, the registrar of Old Prague. Dee hired the whole house from him at a rent of 70 "dollars" or thalers a year, to be paid quarterly…. He announced his return to the Spanish ambassador and to Dr. Curtius….

At this point our author relates Dee’s reservations concerning “the doubting, incredulous spirit of Kelley, which Dee always feels is the hindrance to further knowledge” and says “But Dee was strangely reluctant to part with Kelley. He loved him like a son, he yearned over his soul, and he entertained more lively hopes than ever of his real conversion, for Kelley had at last consented to partake of the sacrament with his older friend….”

Here again we learn from our author that John Dee was in dire financial straights, and that his wife, who was “in great perplexity”, had complained to him "that they had no provision for meat and drink for their family, that it ‘would discredit the actions wherewith they are vowed and linked unto the heavenly majesty’ to lay the ornaments of their house or coverings of their bodies in pawn to the Jews, and that the city was full of malicious slanders. Aid and direction are implored how or by whom they are to be aided and relieved. The spirits, while reminding her grandiloquently that she is only a woman, full of infirmities, frail in soul, and not fit to enter the synagogue, yet favourably listen, and bid her be faithful and obedient as she is yoked, promising that she and her children shall be cared for. Meanwhile her husband is to gird himself together and hasten to see Laski and King Stephan.” The view of the Jews is appropriate for the time. The use of the word synagogue is interesting, but we would not make much of it since it may be an interpretation of the author, rather than the word used by Jane Dee. The point is merely to show that, before John Dee was granted the patronage of the emperor, he was simply too poor to be a spy.

At this point the demons are said to have commanded Dee and Kelley to go to Cracow to see Laski and King Stephan of Poland, and “This injunction seems not to have been obeyed for some time, for Dee was now very busy inditing letters to Queen Elizabeth and to other of his friends in England.” After some dramatic episodes with Kelley and the spirits, Dee and Kelley went to Cracow in April. Continuing with Charlotte Fell Smith from this point:

Laski now joined them in Cracow, and took Dee on May 23 to an audience of King Stephan. Stephan was seated by the south window of his principal audience and banqueting chamber, looking out upon the beautiful new gardens that he was then making. Polite speeches of greeting in Latin passed between the two, but there was scant time for more before the Vice-Chancellor and Chief Secretary, with others, came in, bringing Bills for the King to read and sign. Stephan had small time to spare for visionary alchemists. His very glorious reign was crowded with great achievements. Though a strong Catholic himself, he respected the liberties of his Protestant subjects, won back the Russian provinces for Poland, reformed the universities and established the Jesuits in educational seminaries, and protected the Jews. He died very suddenly about a year after Dee's third interview with him….

Here there is a discussion of Stephan’s death and Dee’s corresponding diary notes, however before that, Dee, Kelley and Laski were entertained by the king on two other occasions. There is also a discussion of the disappointment that Laski was not offering them any money at this time. Kelley is again discouraged. In spite of this situation, we read the following:

Laski was again admitted to the sittings, and King Stephan granted them another interview. Laski urged the King to take the two alchemists into his service and give them "a yearly maintenance." In obedience to his instructors [the demons], Dee promises to make the philosopher’s stone, if the King will bear the charge. He does not profess that he can, but he believes the angels will teach him the secret. Stephan was not so sanguine. In the King's private chamber, a sitting was held, with the crystal set before him, but he remained unconvinced. He gave no encouragement, and in August the pair, hopeless of patronage from Poland, returned to Prague, where Jane and Joan Kelley, the children and the servants, had been left under Edmond Hilton's care.

Returning to Prague, there is a story that some copies of three of John Dee’s books were publicly burned, but that after Dee learned of it, there was somehow a miraculous recovery of the books, where Charlotte Fell Smith suspects some trickery on the part of Kelley, as the books burned had already been copied. With this, “The feeling against these foreign adventurers grew strong in the city. Sixtus V., who had succeeded as Pope, issued a Papal edict, dated May 29, 1586, banishing Dee and Kelley from Prague within six days. It seemed to trouble them very little, for Dee was already away on a visit to a new patron, William Ursinus, Count Rosenberg, at his country seat on the Moldau.” Rosenberg had intervened with the emperor, gained a partial revocation of the decree against them, and put them up at the castle of Trebona, in southern Bohemia, on September 14th, 1586, where they stayed for over two years.

With this, we are not going to continue our description of the adventures of John Dee. While his relationship with Rosenberg helped his fortunes to improve, it helped the fortunes of Kelley to improve even more, before they came to a sad end. The partnership with Kelley ended for good in 1588. Kelley ended up in the favor of the emperor Rudolph, who gave him an estate and a title and made him a position in his court as a councillor of state. But Kelley had evidently done this through chicanery. He was somehow deceiving the emperor with an ability to make gold. After a meteoric rise he then ended up imprisoned by the emperor, where he spent two years. Various possibilities are presented describing how Kelley may have come into disfavor. In December of 1593, Dee received news that his friend was released the previous October. In 1595 Kelley was apparently restored to the emperor’s favor. But John Dee entered into his diary on November 25th, 1595, that he had received news that Kelley had been killed. Of course, this is long after Dee had returned to England.

Smith informs us that “The prevalent story is that Kelley was again imprisoned in one of Rudolph's castles, and that, attempting to escape by a turret window, he fell from a great height and broke both legs, receiving other injuries, from which he shortly died.” She had already repeated speculation that Count Rosenberg was quite powerful politically, so our author tells us that the emperor dared not to execute Kelley openly, but perhaps he was secretly put to death, and the accident was a cover story.

Having stayed at the castle of Count Rosenberg for quite some time, Dee’s fortunes changed dramatically. Kelley and he had parted ways in February of 1588. Dee was receiving what our author called “a princely salary” from the emperor at this time . In 1588 he wrote a letter to Queen Elizabeth congratulating her on the defeat of the Spanish Armada. In it, he proposed a return to England, which was actually about to happen. He departed Trebona with horses and carriages which cost him a large sum, exceeding 600 English pounds. He had an escort of 24 soldiers as far as Oldenburg, and from there to Bremen six musketeers. Smith says that “It was a dangerous time to ride abroad, as he says, not long before the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War. A party of eighteen horsemen had lain in wait for his caravan for five days, but a warning came through a Scot in the garrison of Oldenburg, and Robert, the Landgrave of Hesse, extended his powerful protection.” John Dee and his company arrived in Bremen on April 19th, 1589. Our author states that “In Bremen, Dee mingled with all the learned and distinguished men of the time.” Upon spending some months, then Dee returned to England. Our author tells us:

Dee landed in England a disappointed and a partly disillusioned man, clinging to a belief which was yet useless, unprofitable to him. He could prove nothing of Kelley’s exploits. But he lost no time in repairing and on December 19 he was graciously received by the Queen at Richmond.

We did not repeat the episode at the appropriate time here, but Dee actually believed that Kelley did turn his powder and his mercury into gold, in the presence of both himself and two visitors from England, just prior to his departure for Prague from Trebona the year before.

Regardless of the legends that grew up around John Dee after his death, we have little suspicion that he was ever a spy for the English. Rather, he was a man caught up in Kabbalistic mysticism, turned into an adventurer seeking to support himself through the propagation of his deception, both his own deception and his ability to deceive others, in spite of his own sincerity in pursuit of knowledge. We have every reason to believe that he reported at length to Elizabeth everything which he had heard and seen, and perhaps he was in that sense an accidental spy. But there is no indication that he passed on anything of significant political, military or strategic value during his travels. It is also certainly evident that Elizabeth did not directly support his travels, which she would have been obligated to do if he were travelling in her employment.

But what John Dee did do, was to spread the mysteries of the Kabbalah wherever he went and with whomever he associated, and his travels for that purpose were indeed extensive. What we shall do, is establish this with an examination of some of his work.

Earlier in this presentation, we recounted that John Dee:

After finishing a book of his own in 1564, Monas Hieroglyphica, Dee dedicated it and presented it to emperor Maximillian I. This is significant, because that book has explicit mention of the Kabbalah and presents explicit argument for the mathematical basis of the Kabbalah. For that we shall make a greater presentation in part two of this presentation on John Dee. [This is the presentation we are making here.] Shortly after presenting his book to Maximillian, Dee expressed disappointment that many "universitie graduates of high degree, and other gentlemen, dispraised it because they understood it not," but, speaking of Elizabeth, "Her Majestie graciously defended my credit in my absence beyond the seas." That certainly seems to permit an inference that the academics introduced to Dee’s work in Monas Hieroglyphica were not yet familiar with Kabbalistic philosophy. John Dee returned to England in June of that year, upon which Smith describes more of Elizabeth’s enamorment with Dee. She also describes that when John Dee returned to England, Elizabeth had him tutor her in his new book, Monas Hieroglyphica, with its many references to the Kabbalah. So at this point, John Dee introduced the Kabbalah to Elizabeth I and the court of England.”

Now, over 20 years later, John Dee is in the presence of the emperor Rudolph, and presents him with another copy of the same book, and we read that “Rudolph thanked Dee politely for the book ... adding that it was ‘too hard for his capacity’ to understand”. We would assert that any man who is not fully aware of the perfidy of Jewish philosophobabble may be naive enough to say that such pseudo-intellectual trash is difficult to understand.

There are arguments over whether there was such a thing as a “Christian Kabbalah”, however we would esteem the phrase to be an oxymoron. No such book of truly Christian wisdom should consider to use a term so dear to the Jews. Reuchlin did not promote a Christian Kabbalah, but by his own admissions, a thoroughly Jewish one. John Dee also advanced the Jewish Kabbalah, and not some imaginary “Kabbalah Lite” purveyed to the unsuspecting Goyim.

Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica contains a series of theorems. In them he discussed “the kabbalistic extension of the Quaternary according to the common formula of notation”, the “kabbalistic analysis” of the hieroglyph he offers, and “kabbalistic computation” of what it signifies.

We will read a translation by Hamilton-Jones of his Theorem XVII (we will include a full copy of the translation with the notes to this program):

After a due study of the sixth theorem it is logical to proceed to a consideration of the four right angles in our Cross, to each one of which, as we have shown in the preceding theorem, we attribute the significance of the quinary according to the first position in which they are placed, and in transposing them to a new position, the same theorem shows that they become hieroglyphic signs of the number fifty. It is quite evident that the Cross is vulgarly used to indicate the number ten, and further, it is the twenty-first letter, following the order of the Latin alphabet, and it is for this reason that the sages amongst the Mecubales designated the number twenty-one by this same letter. In fact, we can give a very simple consideration to this sign to find out what other qualitative and quantitative virtues it possesses. From all these facts we see that we may safely conclude, by the best kabbalistic computation, that our Cross, by a marvellous metamorphosis, may signify for the Initiates two hundred and fifty-two. Thus: four times five, four times fifty, ten, twenty-one and one, which added together make two hundred and fifty-two. We can extract this number by two other methods as we have already shown: we recommend to the Kabbalists who have not yet made experiments to produce it, not only to study it in its conciseness, but also to form a judgment worthy of philosophers in regard to the various permutations and ingenious productions which arise from the magistery of this number. And I will not hide from you a further memorable mystagogy: consider that our Cross, containing so many ideas, conceals two further letters if we examine carefully their numerical virtues after a certain manner, so that, by a parallel method following their verbal force with this same Cross, we recognise with supreme admiration that it is from here that LIGHT is derived (LUX), the final word of the magistery, by the union and conjunction of the Ternary within the unity of the Word.

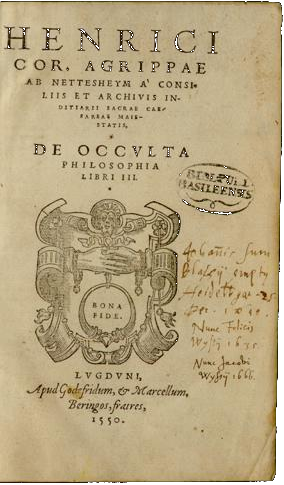

That is exactly what we would call philosophobabble. But among other clues, we see that John Dee’s Kabbalistic influence is indeed the Kabbalah of the Jews in his use of the term Mecubales. Dee was very familiar with the work of his predecessor, whose name we have seen mentioned here several times, the alchemist Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. In chapter 11 Agrippa’s book titled Of Occult Philosophy or Magic, published in Latin at Basel in 1550, we read the following:

That is exactly what we would call philosophobabble. But among other clues, we see that John Dee’s Kabbalistic influence is indeed the Kabbalah of the Jews in his use of the term Mecubales. Dee was very familiar with the work of his predecessor, whose name we have seen mentioned here several times, the alchemist Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. In chapter 11 Agrippa’s book titled Of Occult Philosophy or Magic, published in Latin at Basel in 1550, we read the following:

God himself though he is only one in Essence, yet hath diverse names, which expound not his diverse Essence or Deities, but certain properties flowing from him, by which names he doth pour down, as it were by certain Conduits on us and all his creatures many benefits and diverse gifts; ten of these Names we have above described, which also Hierom reckoneth up to Marcella. Dionysius reckoneth up forty five names of God and Christ. The Mecubales of the Hebrews [by which he could only have meant the Jews] from a certain text of Exodus, derive seventy-two named, both of the Angels and of God, which they call the name of seventy-two letters, and Schemhamphores, that is, the expository…

The reference to the Schemhamphores in the writing of Agrippa is a reference to that same Schemhamphores of the Jewish Kabbalah which Martin Luther openly disdained in his 1543 treatise, On the Jews and Their Lies, which was written seven years before Agrippa’s book was published. Luther could not stop the fire which Reuchlin had started a few decades before him, and with the help of those same humanists that helped to make Luther himself successful.

With this, there should be no doubt that the Kabbalistic influence of John Dee, and Agrippa before him, was the Kabbalah of the Jewish rabbis, and not some supposed so-called “Christian Kabbalah”. Agrippa says on the page which follows that “many names of God and the Angels are extracted out of the holy Scriptures by the Cabalisticall calculation, Notarian and Gimetrian [sic, Gematria] arts”. Then in the neoplatonic tradition, he proceeds by mixing in suppositions and conjectures while evoking the names of Plato, Pythagoras and Zoroaster. It is said of Agrippa, on the page devoted to him at Wikipedia, that at the start of his academic career at the University of Dôle “He was given the opportunity to lecture a course at the University on Hebrew scholar Johann Reuchlin's De verbo mirifico.” There he also wrote a work called On the Nobility and Excellence of the Feminine Sex, a work that tried to prove the superiority of women using cabalistic ideas. So we also see the rise of the Jewish promotion of feminism in late Medieval Christian Kabbalists.

We could continue with this series indefinitely… once the Jews infest a kingdom, there is no end to the web of treachery.

From CARM.org, where our own sentiments are reflected succinctly: “Moses De Leon, a 14th century Spanish Kabbalist presented the Zohar, an extremely influential book in Kabbalistic philosophy. De Leon originally claimed that he found the scrolls that had been written much earlier, more than a thousand years earlier. Recent scholarship supports the idea that he is the one who wrote the Zohar. Present-day Kabbalah is said to have descended through John Dee (1527-1608) who was a mathematician and geographer and Isaac Luria (1534-1572) who is commonly referred to as the greatest Kabbalist of modern times….”

In a somewhat learned essay entitled John Dee and the Kabbalah, which was published in an academic work entitled John Dee: Interdisciplinary Studies in English Renaissance Thought, author Karen De León Jones debates the question as to whether there was really a so-called Christian Kabbalah. In that regard she says “The degree of detailed research indicates that no one seriously doubts that there were Christians not only familiar with Jewish Kabbalah but who considered themselves to be practicing Kabbalists while remaining wholly within whatever form of Christianity they embraced, whether Catholic or Protestant.” With this we must agree. We would consider Reuchlin and Dee to be questionable Christians in practice, but they were nevertheless Christians, at least by birth, heritage and profession. But they were nevertheless disseminating Jewish Kabbalah.

Under the heading “Is John Dee a Kabbalist?” De León Jones writes the following:

In his Monas Hieroglyphica (1564), Dee proposes what he terms the “real Kabbalah”, to set himself apart from the Christian Kabbalistic tradition. In doing so, the uniqueness of his interpretation and the lack of self-definition as a Kabbalist make it difficult to define him as such. Like many of his contemporaries, Dee was familiar with the Christian form of Jewish mysticism known as the Kabbalah, which came into vogue in Renaissance Christian philosophical circles after Giovanni Pico della Mirandola’s publication of the (in)famous Conclusions. Various Christian Kabbalistic texts by Pico, Johannes Reuchlin and others were owned by Dee, even some Jewish ones (those that circulated more freely in Christian circles), often with elaborate commentary. Of the Christian adaptations of the Kabbalah, the thinkers most influential on Dee have already been identified as most likely to have been Cornelius Agrippa and Reuchlin, two of the most renowned thinkers of the period, known even among Jewish Kabbalistic circles. Reuchlin’s De arte cabalistica (1517) and Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia (1533) [which we have just quoted from above] were de rigueur reading, often treated as textbooks or reference guides, for aspiring students of the Kabbalah. The general influence of Reuchlin on Dee, well documented by scholars and attested to by the numerous heavily annotated works by him present in Dee’s personal library, will be discussed later. For now it is crucial to make the point that the influence of Reuchlin’s Kabbalistic precepts is manifest in Dee’s careful definition of the term “Kabbalah” that implies Reuchlin’s differentiation of the significance of the term “Kabbalist” and its employment.

In the preface to the Monas [for some odd reason this was omitted by J.W. Hamilton-Jones in his 1947 translation, which is the only one we have readily available], Dee claims that the Jewish Kabbalah focuses on “what is said”, and is based entirely on grammar, while his is a Kabbalah of “what is.” Therefore Dee consciously sets himself apart from what he considers traditional Christian Kabbalists, emphasizing his differences with them and the uniqueness of his work, rather than points in common. Among these traditionalists are all the Christian Hebraists, who learned Hebrew, often from a converted Jew or New Christian, so as to study the original text of the Old Testament and the Kabbalah. The trend was started by Pico, who learned Hebrew and was initiated into the Kabbalah by the New Christian [or properly, crypto-Jew] Flavius Mithridates [they loved taking fancy Roman names, so they could blend in with German and Italian scholars]. Many others followed, especially in Italy, where there were notable Jewish thinkers of a Neoplatonic and Kabbalistic bent such as Leon Ebreo and Johannes Alemanno (who knew Ficino), to name a few, and where for a period relations between the faiths permitted intellectual exchange.

A Hebraist, Reuchlin himself was heavily influenced by the Italian Neoplatonic School of the fifteenth century originating in Ficino and Pico, seen by him to have directly inherited the Jewish Tradition. Skilled in the language, Reuchlin published a Hebrew grammar and dictionary, for beginners and specialists alike. Although inspired by Pico’s pluralistic vision, his philological knowledge of Jewish texts surpassed Pico’s, as does his mathematical interest. It is likely that Dee was more influenced by Reuchlin in his Kabbalistic thinking than by either Pico or Agrippa. Let us not forget that Dee’s analysis of Kabbalah is intimately linked to his mathematical theories based on Euclidean geometry and Pythagorean theorems. It was Reuchlin who ably defended the idea, inherited by the Italian Neoplatonic School in a mathematically undeveloped form, that Pythagoreanism was directly related to Jewish Kabbalah. 11 He goes so far as to have one of the characters in his famous dialogue, De arte cabalistica, define Pythagoreanism in the same manner as Kabbalah: “The Pythagorean is he who gives credence to what is said, remains silent to begin with, and understands all the precepts.”

Just a little further on De León Jones writes:

If the Monas contains the revelations of the Kabbalah, does this make Dee a Kabbalist? Conveniently, the question of who is and is not a Kabbalist is an ancient one, that Reuchlin attempted to resolve in the following manner in his Ars:

Kabbalah [Cabala] is a matter of divine revelation handed down to further the contemplation of the distinct Forms and of God, contemplation bringing salvation [this is an entirely anti-Christian idea, that salvation can be through the contemplation of man]; Kabbalah is the receiving of this through symbols. Those who are given this by the breath of heaven are known as Kabbalics [Cabalici]; their pupils we will call Kabbaleans [Cabaleos]; and those who attempt the imitation of these are properly called Kabbalists [Cabalistæ]. Exactly this, day by day, they sweat over their published works.

A clear hierarchy, separating the mystic believer from the lay receiver, with a barb at the academics who publish on the material. Already in his time, Reuchlin saw the diffusion of Kabbalah. The last category is seemingly the one Dee fits into, as he is not obviously a receptor of divine revelation in his Kabbalistic writings: one may argue that he is in his angel communications, but these works are marginally related to Kabbalah, at best. We shall see that although his knowledge of Kabbalah itself is certainly of the latter kind, thus of a Kabbalist in the Reuchlinian sense, Dee’s aspirations would be to be considered someone who has achieved the symbolic stratum of the Kabbaleans.

And here we must take issue with De León Jones’ evaluation of Reuchlin’s statements. These are not three distinct categories, but rather, the third step relies upon achievement of the first two. One must be a receptor of the supposed revelation, or a student of such a receptor, before attempting emulation. John Dee actually fits all of these categories. He was without doubt a Jewish Kabbalist in every sense of the word.

A few paragraphs further on De León Jones writes:

This said, I do not diminish the importance of the Kabbalah in the three works influenced by it [referring to three of the important books written by John Dee]: the preface to Euclid’s geometry, Dee’s Aphorisms and Monas. I will even go so far as to claim that these works do more than testify to the general diffusion of the Kabbalah in Elizabethan intellectual circles, but are a unique and interesting example of religious and scientific syncretism in the period. [And in turn it placed the jewish rabbis as the authorities of both religion and science.] Where I draw the line is to declare that the Monas, the most complex and complete of the three works, is a radical new contribution to the development of Christian Kabbalah or that the Monas is a vehicle for Dee’s personal and distinct Kabbalistic revelation. Kabbalah, as defined by Dee, is too real, the way numbers are invisible but “real”, for it to transmit the inexpressible wonder and awe of Creation at the basis of the worship of the Judeo-Christian divinity.

John Dee brought the Kabbalah to England, and he caused the diffusion of Kabbalah among the English intellectuals of the 16th century. After his death, episodes from his life were the subject of satire by great writers such as Ben Jonson and Samuel Butler. We would assert, however, that the damage was done. John Dee introduced to English intellectuals the mysticism of the Jews, and the Jewish rabbis would be its ultimate authorities. Men seeking the supposed secrets which the Kabbalah was said to contain, would have to turn to them for the keys to those mysteries. This could not be done in the universities. Another avenue was necessary, and that opened the door for the Jewish secret societies and the formulation of modern Freemasonry. These seem to have developed from Jewish Kabbalists such as Baruch Spinoza and spread to England through the Rosicrucian movement that materialized in Germany only a short time after John Dee’s death. But John Dee had already blazed the trail to England. We hope one day soon to be able to quantify these assertions further. For now, it is our only conclusion.

John Dee brought the Kabbalah to England, and he caused the diffusion of Kabbalah among the English intellectuals of the 16th century. After his death, episodes from his life were the subject of satire by great writers such as Ben Jonson and Samuel Butler. We would assert, however, that the damage was done. John Dee introduced to English intellectuals the mysticism of the Jews, and the Jewish rabbis would be its ultimate authorities. Men seeking the supposed secrets which the Kabbalah was said to contain, would have to turn to them for the keys to those mysteries. This could not be done in the universities. Another avenue was necessary, and that opened the door for the Jewish secret societies and the formulation of modern Freemasonry. These seem to have developed from Jewish Kabbalists such as Baruch Spinoza and spread to England through the Rosicrucian movement that materialized in Germany only a short time after John Dee’s death. But John Dee had already blazed the trail to England. We hope one day soon to be able to quantify these assertions further. For now, it is our only conclusion.

From a more-or-less official Masonic website, which is also telling tales and lying about our Bibles, in an article titled An Esoteric View of the Rose-Croix Degree: “The first two of the ‘Chapter’ degrees, which serve as a transition between the Lodge of Perfection and the Rose-Croix Chapter, deal with the Second Temple of Jerusalem, built by the Jews returning from the Babylonian captivity, and who brought with them a rich cultural baggage (including the names of the months in Hebrew) and also certain features of oriental mysticism, such as the belief in the after-life, which did not exist earlier in Hebrew traditions.” Freemasonry is Jewish, and is also the root of Christian Zionism, but that too is another story.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.