Martin Luther in Life and Death, Part 1: Did Luther Change the World?

Martin Luther: In Life and Death, Part 1: Did Luther Change the World?

Martin Luther's famous “95 Theses” were written in 1517 and are generally considered to be the catalyst for the Protestant Reformation, however there were certainly many related historical events and many martyrs of reform before Luther came along. Popularly the theses are more fully titled The Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences. My own translation of the original Latin title might be A Dispute Regarding the Proclamation of the Power of Indulgences (Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum). However in spite of its title, besides the sale of indulgences the disputation also protests against many other clerical abuses. It especially mentions nepotism [favoring of family members by church superiors], simony [the purchase of offices within the church], usury [which had recently been allowed by Rome], and pluralism [agreement that other religions have legitimacy, which allows multiculturalism and leads to ecumenism – in Rome at the time, this primarily allowed for the legitimacy of Jews].

Martin Luther's famous “95 Theses” were written in 1517 and are generally considered to be the catalyst for the Protestant Reformation, however there were certainly many related historical events and many martyrs of reform before Luther came along. Popularly the theses are more fully titled The Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences. My own translation of the original Latin title might be A Dispute Regarding the Proclamation of the Power of Indulgences (Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum). However in spite of its title, besides the sale of indulgences the disputation also protests against many other clerical abuses. It especially mentions nepotism [favoring of family members by church superiors], simony [the purchase of offices within the church], usury [which had recently been allowed by Rome], and pluralism [agreement that other religions have legitimacy, which allows multiculturalism and leads to ecumenism – in Rome at the time, this primarily allowed for the legitimacy of Jews].

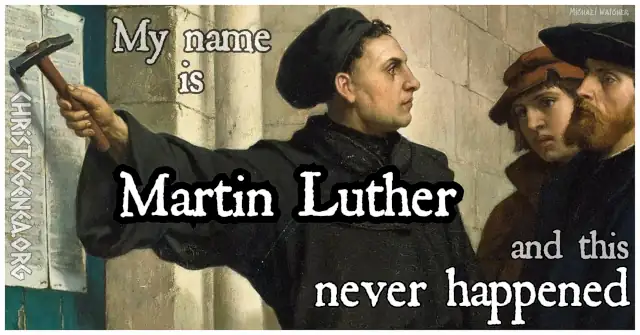

October 31st is called Reformation day, which is celebrated as a religious holiday in many places in Europe. Some sources state that on this day in 1521 Luther appeared before the Diet of Worms. That is not true. Other sources say that October 31st was the day in 1517 that Luther had nailed his 95 “theses” to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. Whether the original publication of his disputation with the Roman Catholic Church ever happened in precisely that manner is also arguable, and here we will see that and several other myths about Luther called into question. Whether or not the story is true, it has for five centuries been used as a powerful symbol representing the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation.

In reality, Luther appeared at the Diet (or imperial meeting) in Worms in April of 1521, and he was released after his appearance as he had been promised safe passage. The Edict of Worms against Luther was a decree issued on May 25th, 1521 by Emperor Charles V. In part it declared that “For this reason we forbid anyone from this time forward to dare, either by words or by deeds, to receive, defend, sustain, or favour the said Martin Luther. On the contrary, we want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic, as he deserves, to be brought personally before us, or to be securely guarded until those who have captured him inform us, whereupon we will order the appropriate manner of proceeding against the said Luther. Those who will help in his capture will be rewarded generously for their good work.”

Martin Luther had stood before the officials of the church and the empire at the Diet of Worms, which was conducted in the bishop’s palace attached to St. Peter's cathedral in Worms for the purpose of hearing Luther. There he steadfastly refused the demands that he recant his teachings and writings. If Luther had recanted at this point then any Reformation of the church could not have come about, and the papal tyranny over Europe would have continued indefinitely. Luther was under enormous pressure to recant, and he quite courageously withstood the life-threatening situation in the presence of the Emperor Charles V.

We are now going to present here an article from John Tiffany entitled “Martin Luther: A Lightning Bolt May Have Changed the World—or Not”. The article itself is based upon, and is a brief attempt at correcting, some of the more fantastic tales of the life, conversion, and career of Martin Luther. Of course, the truth is much more somber, Luther's reform movement was much older than Luther, and the full story will take much longer to present here than a single evening.

However we believe that it is of the utmost importance for Identity Christians today to understand the story of Martin Luther. This is because, although John Wycliffe and then Jan Huss were pushing for similar reforms in the church long before Luther was, Luther was successful far beyond them in convincing the people of Europe to break from a Catholic Church which really did not care to reform at all. Today we need a new Reformation, and only Identity Christians can do so while adhering to the Bible Luther loved so dearly, but did not completely understand.

We hope that starting with the life of Luther, we can eventually move on to an understanding of what happened after Luther, what was going on in the Roman Catholic Church which motivated Luther, and how it all led to what is truly the most tragic event in Medieval history: the Thirty Years' War which began in 1618, 72 years after Luther's death, and which decimated half of Germany.

John Tiffany was for a long time a writer and a frequent contributor to THE BARNES REVIEW. He was assistant editor of that publication when this article appeared there in the July-August, 2008 issue.

Tiffany's article is introduced with the subtitle “Scholars Take A New Look At The Life Of A Religious Icon” For his sources he used two books, one by a German Catholic Scholar and the other by a Harvard professor who was originally from East Tennessee. The first is The Theses Were Not Posted: Luther Between Reform and Reformation, by Erwin Iserloh and published by Beacon Press in I968, and the second is Martin Luther: The Christian Between God and Death, by Richard Marius and published by Harvard University Press in 2000.

With this, we shall proceed with Martin Luther: A Lightning Bolt May Have Changed the World—or Not, by JOHN TIFFANY

[See the following link for a copy of this article which is posted here at Christogenea:]

Martin Luther: A Lightning Bolt May Have Changed the World—or Not

The following excerpts on the life of Martin Luther are from a voluminous work entitled History of the German People at the Close of the Middle Ages by Johannes Janssen, translated from the German by A. M. Christie, and this is from volume 3 of a 16-volume work which we plan on quoting extensively throughout this series.

The life of Luther is presented in this volume within a presentation of what the author calls The Later German Humanism, as humanist philosophy was already well-developed in Europe at the time, and had also already become prevalent in the courts of church bishops and popes as well. For now, we will omit this background and present the paragraphs on the life of Luther. Later on in this series, we shall return to examine the greater historical context. The author introduces the section with Luther's life story first by stating that “At the beginning of this year [referring to 1517 AD] the preaching of indulgences was started, and almost simultaneously the Church was violently convulsed by the appearance on the scene of the Augustinian monk Martin Luther.” Then under the subtitle of “Luther and Hutten” we find an account of Luther's life and early career. The reference to Hutten is a reference to the earlier German Reformer Ulrich von Hutten, who died in 1523 and who was an important catalyst for Luther and a link between Renaissance Humanism and the German Reformation. Here we shall also learn that Luther had his start as a humanist and a doctor of law, and only later, with the lightning bolt described by Tiffany, did Luther turn to Christianity.

Beginning with Volume 3, Page 79 of History of the German People at the Close of the Middle Ages:

Martin Luther was born at Eisenach on November 10, 1483. His youth, passed at Mansfeld, was a period of hardship and suppression, not so much on account of the poverty of his parents as from the extreme severity with which he was treated both at home and at school. He himself relates that his mother once whipped him till he bled, all about a miserable nut, and that another time his father punished him so cruelly that he was filled with hatred against him, and was very nearly running away from home. At school he once got fifteen thrashings in one morning; and with all this beating and misery, he says, he learnt nothing at all. This system of education developed a timid, nervous disposition, and left no room for joyous obedience. It was well calculated to daunt and crush the passionate spirit of the boy, but not to curb and direct it. In his fourteenth year Luther was sent to the school of the Nullbrüder at Magdeburg, and in the following year to the Latin school at Eisenach. So great was his poverty that he was obliged to sing in the streets to earn a crust of bread. His religious feelings were strongly influenced at this period by the solemn church services of the place and the religious plays performed there, and especially by the German hymns, in which the whole congregation used to join during the service.

When he was about sixteen years old a great change took place in his life at Eisenach, owing to the kindness of Frau Cotta, a rich lady of noble birth, who took him to live with her own family. She had taken a great fancy to him, says Luther’s eulogist Mathesius, on account of his beautiful voice and his devout behaviour in church. In 1501 Luther went to the Monastery of Erfurt to study philosophy and law. In 1502 he took the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy, and three years later that of Doctor, after which he was occupied for a short time in lecturing on the physics and ethics of Aristotle.

At Erfurt he pursued zealously the study of the classics ; he read most of the works of the Latin authors, Cicero, Livius, Virgil, and Plautus, attended the humanistic lectures of Hieronymus Emser, and distinguished himself so greatly, says his biographer, that the whole university wondered at his intellectual powers.

Among the younger humanists whose circle he joined, Crotus Rubianus and Johannes Lange were his special friends, but he himself passed among his associates as a musician and a learned philosopher rather than as a poet. He joined heartily in all their social pleasures, and delighted them with his singing and music. But he would often pass suddenly from mirth and cheerfulness to a gloomy, despondent state of mind, in which he was tormented by searchings of conscience. In the year 1505 he sustained a great shock in the sudden death of a friend, who was stabbed in a duel, and in the same year he was caught in a terrific thunderstorm, during which his life was in danger. ‘As I hurried along with the anguish and fear of death upon me,’ he wrote later on, ‘I vowed a vow that was wrung from me by terror.’ Soon after he gathered his friends together at a supper, which was enlivened by lute-playing and singing, and then informed them of the resolve he had made to renounce the world and become an Augustinian monk. ‘To-day you see me,’ he said, ‘but afterwards no more.’ All the entreaties of his friends were useless. They accompanied him, weeping, to the doors of the monastery.

It was characteristic of Luther that the only books which he took with him into his retreat were the pagan poets Virgil and Plautus. What the Dominican monk Peter Schwarz said against exclusive devotion to the classics and the study of law was entirely applicable to Luther up to within the last years before the great crisis of his life. ‘How many men now-a-days study poetry and poetising, and how few study the Holy Scriptures; how many master the subtleties of law, and how few have any knowledge of the Gospel!’ Reuchlin, in like manner, complained that the Scriptures were neglected at the present day for the arts of rhetoric and poetry. While in all the Latin schools which adhered to the traditional Church methods the study of the Bible was carried on assiduously it appears that in the schools which Luther attended, if we may believe his own testimony [as we should], the ancient classics alone were taught. ‘When I was twenty years old I had not yet seen a Bible; I thought there were no other gospels and epistles besides those in the homilies.’ These words are the more astonishing, seeing that when he was twenty years of age he had already been for two years a student at the Erfurt University, where there could have been no lack of opportunity for becoming acquainted with the Bible, which had been a recognised subject of study there ever since the middle of the fifteenth century. Of the still extant manuscript theological works in one of the town libraries of Erfurt exegetical writings make up about one-half; and in 1480 a scholarship was founded at the University of Erfurt for an eight years’ course of study of the Holy Scriptures, ‘with some attention also to canon law.’

‘I entered the monastery,’ Writes Luther, ‘and renounced the World, despairing of myself all the while.’ In spite of the decided objections of his father, who mistrusted Martin’s vocation for the monastic life, and who wished to see his extraordinarily gifted son loaded with worldly distinction and married to a wealthy wife, Luther took the vow of the Eremites of St. Augustine, to live in poverty and chastity after the rule of St. Augustine until death. ‘In opposition to the fifth commandment,’ his father said to him on his consecration as priest, ‘you have forsaken your dear mother and myself in our old age, when we might have expected some help and comfort from you, seeing how much your studies have cost us.’ [The ten commandments are numbered differently among diverse sects and versions. Clearly the commandment to “Honour thy father and thy mother” is what is being referred to.]

It was not in response to a real call that Luther had entered the monastery, but in obedience to a sudden, impetuous resolve, formed after an attack of morbid discontent with his inner spiritual condition; and the means by which, after having become a monk, he endeavoured to obtain the peace he lacked only aggravated his condition. [This assessment is not necessarily true, but reflects a bias which belongs to the historian.] He fell a victim to a morbid hyper-scrupulousness, which was, no doubt, fostered in great measure by the isolation of the monastic life. Simple, unquestioning obedience to the rules of his Order became distasteful to him. It was his duty to say his ‘Horae’ [the official Roman Catholic prayer ritual] daily, but, carried away by his passion for study, he often let weeks go by without taking his breviary in his hand; then he would try to make up all at once for past omissions, would shut himself up in his cell, touch neither food nor drink for several weeks, go without sleep, and torture himself to such an extent that he was once nearly losing his senses. The prescribed rules of ascetic practice did not satisfy him. ‘I imposed on myself additional penances,’ he writes; ‘I devised a special plan of discipline for myself. The seniors in my Rule objected strongly to this irregularity, and they were right. I was a criminal self-torturer and self-destroyer, for I imposed on myself fastings, prayers, and vigils beyond my powers of endurance; I wore myself out with self-mortifications, which is nothing less than self-murder.’ The old monastic proverb was amply verified in Luther: ‘In a monk everything but obedience is despicable.’ Like all hyper-sensitive souls he saw in himself nothing but sin, in God nothing but wrath and vengeance. With this agony of remorse there mingled no feeling of love to God, no childlike hope in His mercy through Christ. The thought of the Deity awoke no emotion in him but that of unmitigated fear, and he was for ever seeking to appease the Divine Wrath by his own righteousness, by the power of works which should bring him into a condition of sinlessness. ‘I was a most outrageous believer in self-justification, a right presumptuous seeker of salvation through works, not trusting in God’s righteousness, but in my own.’

In this way he came gradually to such a condition of hopeless despondency and despair that, as he says, he actually hated God and raved against Him, and hated his own existence, often wishing that he had never been born. ‘From misplaced reliance on my own righteousness,’ he says, ‘my heart became full of distrust, doubt, fear, hatred, and blasphemy of God. I was such an enemy of Christ that whenever I saw an image or a picture of Him hanging on His cross I loathed the sight and I shut my eyes, and felt that I would rather have seen the devil. My spirit was completely broken, and I was always in a state of melancholy, for do what I would my ‘righteousness’ and my ‘good works’ brought me no help or consolation.’ Strange to say, Luther, in later years, attributed this melancholy spiritual condition to the influence of the Church’s teaching concerning good works, while as a fact he was in complete opposition to this, as to all other doctrines of the Church.

Any manual of religious instruction and devotion might have taught him that the Church repudiated all Pharisaic doctrines of self-justification, and considered Christ and His merits as the sole foundation of Christian righteousness, and the grace of Christ as the source of all life and action that was pleasing in the sight of God; and, above all, in the eyes of the Church ascetic practices were merely means to an end, wholesome discipline for weakening and overcoming sinful inclinations with the help of grace, but in no way meritorious actions on which man could build hopes of acceptance with God. ‘Man must fix his faith, hope, and love on God and not on anything created.’ So runs the catechism of Dietrich Roehde, published in 1470. ‘He must trust in nothing but the merits of Christ.’ In the ‘Seelenwurzgärtlein,’ one of the most complete and widely used prayer-books of the time, there stands the following injunction: ‘You must place all your hope and trust on nothing but the merits and death of Jesus Christ.’ ‘Man must die trusting in the mercy of God and not in his own good works,’ says Ulrich Krafft in his ‘Spiritual Conflict’ of the year 1503. Amongst all the books recognised and used by the Church, whether learned works or religious tracts for the people, there is not a single one in which the doctrine of justification through Christ is not clearly set forth.

[Here the translators are disputing with Luther based upon what some German scholars had written earlier. We would not doubt, since there were for a long time struggles and sects put down by the church, and a suppression of the translation of Scripture into the common tongues, that there were not many men who came to these conclusions earlier than Luther. But at this point in his life Luther was not yet a Bible scholar, and his perception was the perception of the common church-goer, rather than the scholar of Catechism. It seems that the translators are defending the Catholic Church from its doctrines without realizing that the Church's dogmas were quite different. Any belief in salvation through sacraments and indulgences and other so-called works does indeed lead to self-justification.]

Whilst this condition of spiritual despair and self-torture continued, Luther found no comfort or relief in receiving the Sacrament. Twice at Erfurt and once in Rome he sought alleviation of his misery by making plenary confession, but it was all in vain. His whole nervous system was so strained and overwrought that when he was at Rome, as he wrote in later years, he almost wished that his parents were dead, so that he might have the joy of releasing them from purgatory by his good works and his Masses. He says that he felt at that time that he might even have become a hideous murderer for the sake of religion, had the opportunity been at hand. ‘I should have been ready to kill any one and every one for daring to refuse obedience to one syllable from the Pope.’

Such a state of religious exaltation could not but be followed by a violent reaction. Racked thus in the innermost depths of his being, and tortured to death by his conscience, Luther ended by passing over to the other extreme. If he had hitherto put overmuch confidence in his own good deeds, he now cast away all reliance whatever on human strength and righteousness in the work of salvation. He began to believe that man, by reason of inherited sin, had become altogether depraved and had no free-will; that all human action whatever, even that which was directed towards good, was an emanation from man’s corrupt nature and therefore, in the sight of God, nothing more or less than deadly sin; that it was by faith alone that man could be saved. ‘When we believe in Christ we make His merits our own possession:’ it was thus that he now taught. ‘We put on the garment of His righteousness, which covers all our guilt and our condition of perpetual sinfulness, and furthermore makes up in superfluity for all human shortcomings; hence, when once we believe, we need no longer be tormented in our consciences.’ ‘Be a sinner if you will,’ he writes to a friend, ‘and sin right lustily, but believe still more lustily, and rejoice in Christ, who is the vanquisher of sin.’ ‘From the Lamb that takes away the sin of the world, sin will not separate men, even though they should commit fornication a thousand times a day and murders as frequently.’

This new doctrine of justification by faith alone Luther considered the central point of Christianity. It summed up for him the whole of Scripture; it was the truth which had long lain hidden on a shelf; he called it, in short, the ‘New Gospel,’ the only medicine for the salvation of Christendom. His teachings, he declared, contained Gospel truth as pure and unadulterated almost as that of the Apostles; what, indeed, did the word ‘gospel’ mean but a new, a good, a joyful message, or good news, the announcement of something that people rejoice to hear? This can never be laws or commandments, for the breaking of which we shall be punished with damnation; for no one would rejoice at such an announcement.

This new doctrine began shaping itself gradually in Luther’s mind in the year 1508, after his appointment to the professorship of philosophy at the Wittenberg university, founded six years before. This post had been conferred on him by the Elector Frederic of Saxony at the instigation of Luther’s intimate friend Johann von Staupitz. Luther’s departure from Erfurt, according to contemporary records of the year 1508, was not a matter of regret to the ‘Brothers’ there, for Luther ‘was always in the right’ in all disputations, and he dearly loved disputing.

At Wittenberg Luther devoted himself chiefly to Biblical and theological studies; he was invested with the dignity of Doctor of Divinity in 1512, and lectured to admiring audiences on the Pauline letters - the letters [letters? sic] to the Romans especially - the Psalms, and St. Augustine. He also gained great fame as preacher in the Cathedral Church. ‘This Brother has deep-set eyes,’ said Martin Pollich, the first rector of the Wittenberg University, of Luther; ‘he must have Wonderful thoughts and ideas.’

Already several years before the outbreak of the indulgence controversy Luther had put himself outside the teaching of the Church by his opinions on grace and justification and the absence of free-will; and in the year 1515, according to the testimony of his eulogist Mathesius, he was denounced as a heretic. ‘Our righteousness,’ he said in a sermon preached at Christmas 1515, ‘is only sin; each one of us, therefore, must accept the grace offered by Christ.’ ‘Learn, dear brother,’ he wrote on April 7, 1516, to the Augustinian George Spenlein at Memmingen, ‘learn to despair of thyself and say: “Thou, Lord Jesus, art my righteousness; I am Thy sin. Thou hast taken what is mine and given me What is Thine.” Only through Christ, and through utter abnegation of thyself and thine own works, shalt thou find peace.’ He was already so firmly convinced of the truth of this teaching that he added an anathema to it: ‘Cursed be whoever does not believe this.’ His tenets are expressed in the most outspoken terms in the report of a disputation held at the university in September 1516, on which occasion he had asked to be elected president of the debate - an honour which ought by right to have been conferred on another member. In this discussion the following thesis, among others, was defended: ‘Man commits sin whenever he acts according to his own impulses, for of himself he can neither think nor will rightly. Of the twenty-nine theses which he wrote out for a Doctoranden [evidently a paper written by a PhD student] the fourth runs thus: ‘The truth is that man, after having become a corrupt tree, can will and do nothing but what is bad; ’ and the 5th: ‘It is false to say that the will of man is free and can decide one way or another: our wills are not free, but in captivity.’

It was during the Lent of 1517 that he began preaching his new tenets openly among the people. In these sermons he inveighed fiercely against those vain babblers who had filled Christendom with their chatter, and had misled the poor credulous folk with their pulpit utterances, telling them that they ought to have or to cultivate good wills, good intentions, good ways of thinking. where no will whatever existed, Luther taught them, God’s will was the best of all.

Already in July 1517, three months before the beginning of the indulgence controversy, Duke George of Saxony expressed his fears of the effect of such teaching on the people. When Luther proclaimed, in a sermon preached at Dresden on July 25 by desire of the Duke, that the mere acceptance of the merits of Christ insured salvation, and that nobody who possessed this faith need doubt of his salvation, the Duke said more than once at table, in serious earnest, ‘he would give a great deal not to have heard this sermon, which would only make the people restive and mutinous.’

Luther’s doctrines, for which he thought he found support in St. Augustine, had spread through the whole University of Wittenberg, so he writes, as early as the year 1516.

It was after October 31, 1517, that they began to be disseminated throughout Germany.

It was on this day that Luther, incensed by the indulgence preacher Johann Tetzel, affixed to the church door at Wittenberg twenty-nine theses attacking the virtue of indulgences.

So here we shall leave off with the life of Luther, for now. And while we come around to the argument as to whether Luther really nailed his theses to the door or not, the story is nevertheless representative of the firestorm which Luther's teachings would set off, as it is a direct affront not only to the authority of the church and its dogmas, but also a threat to the authority of the State which we see was already realized by Duke George of Saxony.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.