The Protocols of Satan, Part 38: William Jennings Bryan, the Last Viable Political Opposition

The Protocols of Satan, Part 38: William Jennings Bryan, the Last Viable Political Opposition

The following is a presentation of part of a speech by William Jennings Bryan which was published in The Barnes Review in their March/April 2000 issue. We are presenting this here this evening, as well as an earlier and longer article focusing on Bryan’s political career which was written by Michael Collins Piper in 1996, in order to show that there was viable political opposition to the internationalist designs which ultimately prevailed in the late 19th and early 20th century American politics. However we see William Jennings Bryan as the last of such viable political opposition, and he was defeated time and again, until he finally relented – and later regretted it. Of course, later on there was Huey Long, but the plutocrats had him killed before he ever became a threat.

Imperialism Is Not The American Way by William Jennings Bryan

The editor of The Barnes Review introduces the speech with a description of a cartoon which was reproduced on the issue’s front cover:

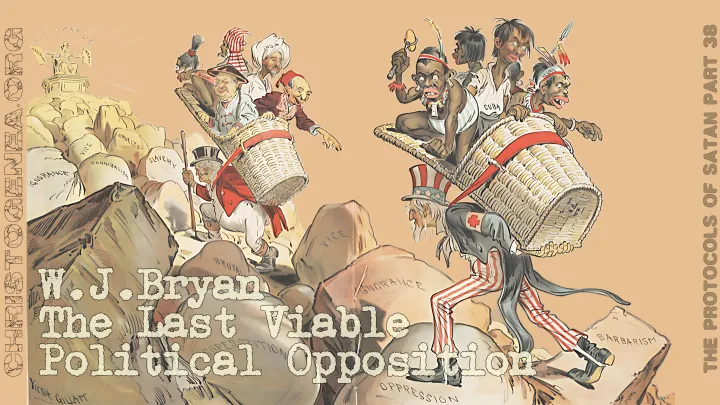

At the dawn of the 20th century, when “the old horse got too slow for Uncle Sam” (as the Judge cartoon which is our cover illustration this month so quaintly put it), one of the most vociferous critics of the newly burgeoning U.S. internationalism (soon to be called "gunboat diplomacy") was populist figure William Jennings Bryan, known as “the Great Commoner.”

The cartoon, pictured here, may have been better described. According to Wikipedia, “Judge was a weekly satirical magazine published in the United States from 1881 to 1947.” Reportedly the magazine openly supported the Republican Party. However the many Victor Gillam cartoons which it published expressed sentiments which were against immigration, internationalism and imperialism, things which the Republican Party had supported. William Jennings Bryan was anti-Imperialist and populist Democrat.

In our last presentation of these Protocols of Satan, presenting The Menace of the Money Power, we saw A. K. Chesterton describe the Jewish bankers’ promotion of the Gold Standard, and how the Sherman Silver Act of the 1890’s and the issue of silver certificates stood in the way of their plans. This examination of William Jennings Bryan by Piper will also help us to understand these issues and how they were debated at the time.

Now our editor prefaces the Bryan speech against imperialism with a description of Bryan himself:

A former member of Congress from Nebraska, Bryan was the Democratic Party's presidential candidate in 1896, 1900 and 1908, and although he achieved a national following and was practically a legend in his own time, he never occupied the Oval Office. Appointed secretary of state by Woodrow Wilson in 1912, Bryan resigned that post in disgust when it became clear that the Wilson administration, dominated by international money interests, was determined to bring the United States into the war then raging in Europe.

The big national issue during Bryan's 1896 presidential campaign against Republican William McKinley was the issue of money. However, four years later, when McKinley sought reelection, once again facing Bryan as his challenger, the big national issue had turned to imperialism.

What follows is an abbreviated excerpt from Bryan's speech on the subject of imperialism that he delivered during the heat of the 1900 campaign. In fact, Bryan's point of view on the subject hardly differs from the modern-day populist viewpoint on globalism and, in many respects, echoes many of the points that Pat Buchanan is making today in his own bid for the presidency.

This was March of 2000, and the Presidential elections were months away. Buchanan, a former adviser to Republican presidents Ford and Reagan, left the party in 1999 and ran as a populist on the Reform Party ticket, a place previously occupied by Ross Perot. He only managed to win only 0.4% of the electorate, not quite 450,000 votes. This is embarrassing, since in contrast Perot received nearly 20 million votes in 1992, and then in 1996, even after he was excluded from the televised debates, he still received over 8 million votes. But if anything killed Buchanan’s credibility, it was his choice of a negress for his vice-presidential running mate.

Left: William Jennings Bryan, "the Great Commoner," lived from 1860 to 1925. His fierce denunciations of American empire-building at the turn of the 20th century would prove to be still as valid, inspiring and cutting today as they were then. Some of his views on American imperialism remain the standard for Constitutionalists and non-interventionists today. In 1912 he helped Woodrow Wilson become president and was rewarded with the office of secretary of state, but he quit that position when he broke with Wilson over U.S. policy following the sinking of the Lusitania. Above, he accepts his third Democratic nomination for the presidency on the steps of the Nebraska Capitol, 1908.

Actually, as Michael Collins Piper will allude later on, Bryan’s function as secretary of state was being undermined by the so-called Colonel, Edward Mandell House. We discussed House at length in Part 19 of this series on the Protocols, which was subtitled Jewish Agents in Post-Protocols American Government.

Now we will present the amended text of Bryan’s speech, which is actually just a few paragraphs that The Barnes Review editors had extracted from a lengthy speech which Bryan had presented to a committee of the national leadership of the Democratic Party on August 8th, 1900:

Those who would have this nation enter upon a career of empire must consider not only the effect of imperialism on the Filipinos, but they must also calculate its effects upon our own nation. We cannot repudiate the principle of self-government in the Philippines without weakening that principle here.

Lincoln said that the safety of this nation was not in its fleets, its armies or its forts, but in the spirit which prizes liberty in the heritage of all men, in all lands, everywhere. And he warned his countrymen that they could not destroy this spirit without planting the seeds of despotism at their own doors.

Even now we are beginning to see the paralyzing influence of imperialism. Heretofore this nation has been prompt to express its sympathy with those who were fighting for civil liberty. While our sphere of activity has been limited to the Western Hemisphere, our sympathies have not been bounded by the seas. We have felt it due to ourselves and to the world, as well as to those who were struggling for the right to govern themselves, to proclaim the interest which our people have, from the date of their own independence, felt in every context between human rights and arbitrary power.

Of course, Lincoln himself was one such tyrant, who denied the people of the South the right to govern themselves by force of arms. We do not know whether Bryan understood the hypocrisy of quoting Lincoln in this context, however Bryan himself was merely a politician. Perhaps he sought to exploit the fact that Lincoln was a Republican who at least verbally agreed with these sentiments. As for the Philippines, it matters not whether Bryan cared for aliens, what matters is that he is asserting that the U.S. should treat foreign nations in the same way that its own founding documents declared the right of a people to self-government. In a portion of this speech which was not reproduced by the editors, we read: “If it is right for the United States to hold the Philippine Islands permanently and imitate European empires in the government of colonies, the republican party ought to state its position and defend it, but it must expect the subject races to protest against such a policy and to resist to the extent of their ability.” the Philippines were recently won from Spain, and eventually granted independence, but not until 1946. Ever since then, Philippinos have been colonizing America – at least since the Immigration Act of the 1960’s.

Interestingly, in 1899 Rudyard Kipling wrote his famous poem, “The White Man's Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands”, which was evidently meant to encourage the United States’ civilizing of the Philippines, and Judge magazine published another Victor Gillam cartoon borrowing from Kipling’s title, “The White Man's Burden. (Apologies to Rudyard Kipling.)” The cartoon pictures both Uncle Sam and John Bull climbing a hill to civilization. On John Bull’s back is a basket full of Asians, while Uncle Sam toils under a basket full of Negros. The boulders which serve as obstacles to their ascent are marked with words such as brutality, superstition, ignorance, vice, cannibalism etc., all of the traits of the non-White races which they by themselves have never been able to overcome. Of course, the prevailing egalitarianism prevented men of the time from realizing that these other races could never overcome such challenges, regardless of how far they are carried by White men. Generally, we still have not learned that lesson today. Despite the observable events of a hundred years, most of us are still foolishly egalitarian.

Continuing with Bryan’s speech:

Three-quarters of a century ago, when our nation was small, the struggles of Greece aroused our people, and Webster and Clay gave eloquent expression to the universal desire for Grecian independence. In 1898 all parties manifested a lively interest in the success of the Cubans.

The reference to Greece is to the so-called Greek War of Independence of the 1820’s. For over 500 years much of Greece, and most of the rest of the former Byzantine Empire, was under Ottoman rule. Independence was officially gained in 1830, after intervention by the British, French and Russians on the side of the Greeks. The reference to Cuba is in relation to the Spanish-American War, after which Cuba gained independence from the U.S. in 1902. Continuing with Bryan:

But now when a war is in progress in South Africa, which must result in an extension of the monarchical idea or in the triumph of a republic, the advocates of imperialism in this country dare not say a word in behalf of the Boers ...

Our opponents, conscious of the weakness of their cause, seek to confuse imperialism with expansion, and have even dared to claim Jefferson as a supporter of their policy. [But] Jefferson spoke so freely and used language with such precision that no one can be ignorant of his views. On one occasion he declared: "If there be one principle more deeply rooted than any other in the mind of every American, it is that we should have nothing to do with conquest." And again he said: “Conquest is not in our principles; it is inconsistent with our government.”

Imperialism would be profitable to the army contractors; it would be profitable to the ship owners who would carry live soldiers to the Philippines and bring dead soldiers back; it would be profitable to those who would seize upon the franchises; and it would be profitable to the officials whose salaries would be fixed here and paid over there; but to the farmer, to the laboring man and to the vast majority of those engaged in other occupations it would bring expenditure without return and risk without reward...

If there is poison in the blood of the hand, it will ultimately reach the heart. It is equally true that forcible Christianity, if planted under the American flag in the far-away Orient, will sooner or later be transplanted upon American soil...

Imperialism finds no warrant in the Bible. The command “Go ye into all the world and preach the a gospel to every creature, has no Gatling gun attachment.”

Evidently at least some politicians of the time must have been using religion as a reason to advocate for empiricism. This is only a brief snapshot of the political issue of the day, in the year 1900. But not even Bryan may have seen the larger picture. An anti-imperialist America is anathema to the internationalist Jew, who would not have been able to move the center of his empire from London to New York, and who would not have had the world’s largest plantation of White blood to freely harvest for use in his wars of world conquest.

But imperialism was introduced by two methods, and evidently Bryan did understand that. One method is commercial, and the other, religious. It was as early as the 15th century that imperialist forces within the Roman Catholic Church began to abuse certain Scriptures as an excuse by which to force Church rule over alien peoples. So here we see that this idea that the heathens should be forced to accept Christianity was also circulating in 19th century America, even though it was dominated by Protestants.

Identity Christians should already understand that first, the word world as it is used in the Bible is misunderstood, and second, the Christian gospel was only to be brought to certain nations as it is explained by the apostles of Christ: to the twelve tribes which were scattered throughout Mesopotamia and Europe. Finally, the passage quoted here by Bryan is from Mark chapter 16, and a spurious portion of the Gospel of Mark which was added some time after the fourth century of the Christian era. The Imperialist Christianity which developed in Rome is a Jewish corruption so that Christianity could be ultimately subverted for their purposes.

In our last presentation of these Protocols of Satan, we witnessed the assertions of A. K. Chesterton, that the international bankers needed to have the nations of the world on a common currency standard, for which they chose gold, before they could subsume those nations into their super-national central banking system. It would be our contention that once it was ascertained that America submitted to a gold standard, that in turn paved the way for a central bank, as Chesterton explained, and that in turn would pave the way for the use of America as a military tool in the overseas ventures of that same cabal of Jewish bankers. [As a digression beyond the scope of our purpose here, in the 1960’s the gold standard was made obsolete by the world banking system which was by then thoroughly entrenched.] So now, in order to substantiate the steps taken in the culmination of this process, we feel that there is no better witness than the political career of William Jennings Bryan, who was the most prominent of the opposition of his time to each of those steps as they were being implemented. Running for president in 1896, Bryan was the anti-gold and pro-silver candidate. Running for president in 1900, he was the opponent of imperialism.

But we must also warn, that while William Jennings Bryan was a Christian, he is not an ideal Christian Identity icon. While he made many speeches promoting Christianity and the importance of Christian morals, and while he was a vocal opponent of Darwinism and other modernist contrivances, he was nevertheless a liberal egalitarian, and his views on governance reflected his liberalism. He thought, for example, that America should be engaged in using her power to spread democracy to alien nations abroad. So he may not have been an imperialist of government, but he was a universalist egalitarian, and an imperialist of ideas, just another politician trapped in the philosophical box designed by medieval Jews.

Now we shall present an article from the November, 1996 issue of The Barnes Review,

William Jennings Bryan - The Populist Warrior by Michael Collins Piper

While we would agree on many subjects, I would consider Piper an intellectual opponent, and before he died I challenged him on Facebook to discuss certain things with me, especially Christianity. Instead of discussion, I was trolled by his friend, the Arab bastard and blogger Mark Glenn, and several others operating behind sock-puppet accounts. I suspected that one of them was Wayne Prante, who attempted to disparage me as a racist in Facebook threads with Piper. Then Piper died unexpectedly in 2015. In spite of his faults, he did some very good work in certain areas of history, and I think this is one of those areas.

The introduction to our article reads:

In 1896, the forces of American populism rallied behind Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. For the first time, our political arena filled with the drama of middle America's champion squaring off against the international plutocratic interests. Controversy over the nation's money system was the core issue of the day. Americans from all walks of life freely debated the question of our monetary structure. Today the subject is virtually taboo. What a difference a century makes.

And of course, today people are not even cognizant that they should question the money structure. They do not even care to understand where money comes from or by whom and how it is made. But the reasons for that ignorance and indolence have already been boasted of in the Protocols. Piper begins:

In 1896 the Democratic Party held its national convention in Chicago, nominating William Jennings Bryan for the presidency. A hundred years later the Democrats again gathered in Chicago, to renominate President Bill Clinton. This year the Democratic Party's national convention was a tightly orchestrated love-fest. In 1896, the party was split down the middle.

Congressional Quarterly's 1976 Guide to U.S. Elections stated “The Democratic convention that assembled in Chicago in July, 1896 was dominated by one issue – currency. A delegate's viewpoint on this single issue influenced his position on every vote taken. Generally, the party was split along regional lines, with eastern delegations favoring a hard-money policy with maintenance of the gold standard, and most southern and western delegations supporting a soft-money policy with the unlimited coinage of silver." [Congressional Quarterly. Guide to U.S. Elections, (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly, 1976), p. 50.]

Right: William Jennings Bryan is pictured in 1896, about the time he received his first presidential nomination. In the mid-term 1894 elections, People's (populist) Party candidates received a surprising vote of over 1.4 million. Their largely rural strength was essentially based on the championing of free silver. Bryan won most of their 1896 support. There were of course “Silver Republicans” and “Gold Democrats” who reflected their agrarian or industrial area interests. The backing of urban working men and Union army veterans proved decisive for William McKinley.

Right: William Jennings Bryan is pictured in 1896, about the time he received his first presidential nomination. In the mid-term 1894 elections, People's (populist) Party candidates received a surprising vote of over 1.4 million. Their largely rural strength was essentially based on the championing of free silver. Bryan won most of their 1896 support. There were of course “Silver Republicans” and “Gold Democrats” who reflected their agrarian or industrial area interests. The backing of urban working men and Union army veterans proved decisive for William McKinley.

In virtually every respect, the Democrats of 1996 are nothing like the Democrats who nominated William Jennings Bryan in 1896, although they certainly wanted to recall Bryan's populist appeal. Since U.S. Grant's successful Republican bid for the presidency in 1868, entire state GOP delegations from the South were totally or largely composed of blacks.

Left: Bryan's third and last hurrah as a presidential nominee was in 1908. Here he campaigns against outgoing President Theodore Roosevelt's chosen successor, William Howard Taft. No burning issues separated the major party candidates. Both opposed monopolistic trusts and supported a graduated income tax. Minor party candidates included populist Thomas E. Watts, Socialist Eugene V. Debs and, ominously, prohibitionist Eugene W. Chafin.

Left: Bryan's third and last hurrah as a presidential nominee was in 1908. Here he campaigns against outgoing President Theodore Roosevelt's chosen successor, William Howard Taft. No burning issues separated the major party candidates. Both opposed monopolistic trusts and supported a graduated income tax. Minor party candidates included populist Thomas E. Watts, Socialist Eugene V. Debs and, ominously, prohibitionist Eugene W. Chafin.

Of course, Taft won the 1908 election. But in spite of being Roosevelt’s hand-picked successor, in 1912 Roosevelt would enter the race as a third-party candidate, who finished second and split his party’s vote with Taft to ensure the victory of Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Continuing with Piper, who had just described the Negro prevalence in the Republican Party in the South:

Most American Jews of the time and the ever increasing numbers of Eastern European Jewish immigrants allied with the GOP; favoring its financial policies and rightly perceiving it as the “social activist” party. The Democrats of that era were the party of a patriotic (and essentially segregationist) middle and lower middle America. The massive party identity shifts would not begin to occur until the Franklin D. Roosevelt administrations.

As columnist Robert Novak commented: “In the weekend festivities preceding the convention, there was an actor's recitation in Grant Park [in Chicago] of William Jennings Bryan's ‘Cross of Gold’ speech during platform debate at the 1896 Democratic National Convention. It is hard to imagine a major party nominating anybody who dispensed such claptrap about free silver coinage, agrarian populism and the struggle by the masses against commercialism.… In 1996, Democrats won't even debate their platform,” he predicted. [Robert Novak, writing in The Washington Post, August 26, 1996, p. A13.]

Of course, Novak is also a Jew. Piper is evidently borrowing his comparison of the two elections. The free silver concept comes from the basic notion that the resources of the land belong collectively to its people, and the people should therefore benefit collectively from the resources. Continuing with Piper:

Novak was right about this year's gathering [1996]. As he later noted, it was “the most peaceful, unified Democratic National Convention in memory.” Yet he pointed out: “Democrats have been fighting about platforms throughout their history.” [Robert Novak, writing in The Washington Post, August 29, 1996, p. A23.] In 1996, though, that was hardly the case.

Tom Johnson, the populist mayor of Cleveland, called the 1896 election “the first great protest of the American people against monopoly – the first great struggle of the masses in our country against the privileged classes. It was not free silver that frightened the plutocrat leaders. What they feared then, what they fear now, is free men. [Stefan Lorant, The Glorious Burden. (Lenox, Massachusetts: Authors Edition, Inc., 1976), p. 445.]

An outgoing Democratic incumbent occupied the White House in 1896. President Grover Cleveland was completing his second (non-consecutive) term, but he was by no means in control of his party. The chief executive from Buffalo, N.Y., like many in the Eastern wing of his party, was a “Gold Democrat.” But since the president was not seeking re-election, the party and its convention were wide open – and ripe for a split.

According to historians R. Craig Sautter and Edward M. Burke: “In the politics of 1896, support for gold was a declaration of allegiance to the Eastern banks and the large corporate holdings they financed and the economic prosperity they promised. To declare for silver was to side with Southern and Western farmers and for working men and women whose standard of living was crushed under half a decade of the worst depression the United States had yet experienced. Silver as a political issue represented a dire cry for relief from insurmountable personal debt. As the 1896 election approached, the silver forces represented constituencies that were on the verge of open economic rebellion and violence.” [From R. Craig Sautter and Edward M. Burke's Inside the Wigwam: Chicago Presidential Conventions 1860-1996 (Wild Onion Books, 1996); Excerpts published in the August 26, 1996 issue of Roll Call, Washington, D.C.]

Ironically, Cleveland's Republican opponent in the 1888 campaign, James G. Blaine, had endorsed silver. However, by 1896 the Grand Old Party had firmly endorsed gold, taking the same position as the Democratic president. This led to some interesting maneuvering within both parties.

Here we see that the phenomenon of Democrats and Republicans sharing the same policy regardless of its utility to the nation is nothing new. Piper continues:

Three weeks before the Democratic convention the Republicans convened in St. Louis and nominated the popular 53-year-old Ohio Governor William McKinley on the first ballot.

A Civil War hero who had served in Congress (where he was nationally known as the author of protectionist trade measures), McKinley was, actually, a bimetallist. He advocated joint usage of gold and silver in regulating the nation's economic affairs. However, McKinley and his closest political strategist, Ohio industrialist Marcus A. “Mark” Hanna, another bimetallist, accepted the GOP's gold plank in order to get the party's endorsement. [Hanna was evidently of Scotch-Irish and English descent. - WRF] They sensed, correctly, that endorsement of gold would be a sure way to win the support of the Eastern financial interests. These titans were watching events within the Democratic Party with great concern.

Writing in Tragedy and Hope, Georgetown University Professor Carroll Quigley described the events leading up to that momentous Democratic convention of 1896:

“The inability of the investment bankers and their industrial allies to control the Democratic Convention of 1896 was a result of the agrarian discontent of the period 1868-1896. This discontent in turn was based, very largely, on the monetary tactics of the banking oligarchy. The bankers were wedded to the gold standard… Accordingly, at the end of the Civil War, they persuaded the Grant Administration to curb the post-war inflation and go back on the gold standard… This gave the bankers a control of the supply of money.

“The bankers’ affection for low prices was not shared by the farmers, since each time prices of farm products went down the burden of farmers’ debts (especially mortgages) became greater. Moreover, farm prices, being much more competitive than industrial prices, and not protected by a tariff, fell much faster than industrial prices, and farmers could not reduce costs or modify their production plans nearly as rapidly as industrialists could.

“The result was a systematic exploitation of the agrarian sectors of the community by the financial and industrial sectors. This exploitation took the form of high industrial prices, high (and discriminatory) railroad rates, high interest charges, low farm prices, and a very low level of farm services by railroads and the government.”

We have already seen from A. K. Chesterton, how Jacob Schiff and Kuhn, Loeb & Co. had already gained control of two major railroads by this time, Union Pacific Railroad and the Great Northern Pacific Railway. Continuing with Piper:

“Unable to resist by economic weapons, the farmers of the West turned to political relief, but were greatly hampered by their reluctance to vote Democratic (because of their memories of the Civil War). Instead, they tried to work on the state political level through local legislation (so-called Granger Laws) and set up third-party movements (like the Greenback Party in 1878 or the Populist Party in 1892). By 1896, however, agrarian discontent rose so high that it began to overcome the memory of the Democratic role in the Civil War.

So the farmers of the West were well indoctrinated by the Union view of history which unjustly places blame for the War of Northern Aggression on the South and the Democratic Party, at least according to Quigley. Perhaps one day we will be able to examine post-War propaganda from this perspective. Once again, continuing with Piper:

“The capture of the Democratic Party by these forces of discontent under William Jennings Bryan in 1896, who was determined to obtain higher prices by increasing the supply of money on a bimetallic rather than a gold basis, presented the electorate with an election on a social and economic issue for the first time in a generation.” [Carroll Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, (Hollywood, California: Angriff Press, 1974), p.74]

The opening functions of the convention signaled that the silver forces were in command of the Democratic Party in 1896.

Sautter and Burke wrote: “The band played Dixie as the silver candidate, Sen. John W. Daniel of Virginia, defeated the national committee's candidate, New York's David Bennett Hill, for the position of temporary chairman… Daniel's victory was greeted with waves of enthusiastic endorsement among the silver delegates that lasted nearly half an hour. The early victory signaled that a strong silver contingent had made its way to Chicago from the state conventions.” [Sautter and Burke, Ibid.]

With the final vote on adoption of the party's platform plank on money, tensions ran high. There was even a call for the impeachment of President Cleveland by Senator "Pitchfork Ben" Tillman of South Carolina. He called the president “a tool of Wall Street,” and angrily denounced “Cleveland Republicanism.”

It was during the platform debate over the money question that it became evident that William Jennings Bryan would win the Democratic Party's presidential nomination. For nearly a generation thereafter, he would be recognized as the leading national voice of the American populist movement.

Born in Salem, Illinois on March 19, 1860, Bryan was graduated from Illinois College in 1881. After studying at the Union College of Law in Chicago, he opened a law office in Jacksonville, Illinois. But his law practice drew him westward and he settled in Nebraska, in 1887. Bryan became active in the Democratic Party in his adopted state, delivering his first (and well-accepted) political speech in 1888.

Having married Mary Baird in 1884, Bryan soon discovered he also had an active political helpmate. No shrinking violet, Mrs. Bryan was college educated and took up the study of law. Eventually she was admitted to practice by the Supreme Court of Nebraska. She had little personal interest in the business of law. Mrs. Bryan was interested in helping advance her husband's career, and felt knowledge of the law would prove beneficial.

Tongue in cheek, here we may quip that the adoption of aspects of society which seem feminist are permissible if a woman is helping her husband, which is an anti-feminist position. Oh, the quandary!

Already known as a skilled orator, Bryan was elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1890 and re-elected in 1892. He ran for the Senate in 1894, but was defeated. However, during his short tenure in Congress, Bryan established himself as an able political strategist and built a national reputation. From 1894 to 1896 he retired to the field of journalism. He kept active in the public arena, particularly in regard to the growing controversy over the money question.

In 1894, Bryan ran for the Senate in Nebraska as a Democrat against Republican John Thurston. We have already seen it explained how unpopular Democrats were in the West. Bryan received less than 13% of the vote, and a third-party candidate did slightly better. While Nebraska elected Populist Party senators in 1893 and 1899, it did not elect a Democrat as senator until 1911. Continuing with Piper:

Leading a pro-silver delegation from Nebraska to the 1896 Democratic convention, Bryan was in the right place at the right time.

Right: In 1914, Secretary of State Bryan became enraged by Britain's early wartime disregard of treaty documents and related inter-power agreements. Although technically America could trade with Germany, His Majesty's government added petroleum and some 800 “nonmilitary” items to its blockade list. In an earnest but near-farcical 1915 attempt to achieve peace, he forged the Bryan Peace Treaty. Above, Bryan (center) signs with representatives of Great Britain, France, Spain and China.

Right: In 1914, Secretary of State Bryan became enraged by Britain's early wartime disregard of treaty documents and related inter-power agreements. Although technically America could trade with Germany, His Majesty's government added petroleum and some 800 “nonmilitary” items to its blockade list. In an earnest but near-farcical 1915 attempt to achieve peace, he forged the Bryan Peace Treaty. Above, Bryan (center) signs with representatives of Great Britain, France, Spain and China.

Below: Bryan's last crusade, his prosecution of the Scopes “Monkey Trial” in Tennessee, would remain one of his most memorable. Here, seated right, he is photographed with the famed (and not always legally fastidious) defense attorney, Clarence Darrow. The nationally followed proceedings had taken a great deal out of the energetic warhorse. The jury agreed with Bryan. Defendant John Thomas Scopes was fined $100 and court costs, the legal minimum. However Bryan died the following Sunday. He had delivered a church oration in Dayton, Tennessee, and in the afternoon succumbed to diabetes mellitus; the immediate cause attributed to the trial's heat and exertions.

Although the pro-silver forces had largely prevailed throughout the convention, by the time of the platform debate the rhetoric was so harsh and so pitched that even the silver forces sensed their position was weakening. They needed forceful action to reclaim the initiative.

Although the pro-silver forces had largely prevailed throughout the convention, by the time of the platform debate the rhetoric was so harsh and so pitched that even the silver forces sensed their position was weakening. They needed forceful action to reclaim the initiative.

Sautter and Burke describe that critical moment: “The silver forces needed to regain control of the controversy. At this moment, a handsome, slim, six-foot, 36-year-old former two-term Congressman from the Nebraska silver delegation leaped to the speaker's stand two steps at a time. He wore a stylish black alpaca coat, Western boots, pants that bagged at the knees, and a white string bow tie… Amid the waving state banners and tossed hats, the crowd finally held its breath as the speaker stood for several minutes motionless, statuesque against the sea of waving handkerchiefs. The delegates and even the spectators sensed that they were about to be lashed by a verbal storm.

“Bryan appeared like a Democratic Apollo before them, his figure chiseled against the portraits of former presidents, his head tossed back, his hand upon the podium… Though a lawyer of the highest quality, Bryan did not answer in kind the legalistic arguments of the gold men. Instead he elevated his political battle for silver to a moral and spiritual plane that would typify the campaigns he fought all his long life. His beautifully melodic voice resonated lute-like in the hearts of his sympathizers.” [Ibid.]

Bryan then proceeded to deliver one of the most momentous and oft-referenced political orations in all of recorded history. Acknowledging the strife within his party ranks, Bryan said:

Never before in the history of this country has there been witnessed such a contest as that through which we have just passed. Never before in the history of American politics has a great issue been fought out as this issue has been, by the voters of a great party.

In this contest brother has been arrayed against brother, father against son. Old leaders have been cast aside when they have refused to give expression to the sentiments of those whom they would lead, and new leaders have sprung up to give direction to this cause of truth. Thus has the contest been waged, and we have assembled here under as binding and solemn instructions as were ever imposed upon representatives of the people.

Turning to the gold delegates, Bryan declared:

When you come before us and tell us that we are about to disturb your business interests, we reply that you have disturbed our business interests by your course.

We do not come as aggressors. Our war is not a war of conquest; we are fighting in the defense of our homes, our families, and posterity. We have petitioned, and our petitions have been scorned; we have entreated, and our entreaties have been disregarded; we have begged, and they have mocked when our calamity came. We beg no longer; we entreat no more; we petition no more. We defy them.

Now we can honestly say that all of this division was unnecessary, as it was the bankers themselves who were driving the economic policy in a direction which would push the nation to accept a gold standard. The economy was bad because that is what the bankers wanted, as we had also saw Chesterton attest in our last presentation. Continuing with Piper:

Responding to critics who said the Silverites were demagogues – potential tyrants, Bryan thundered:

In this land of the free you need not fear a tyrant that will spring up from among the people. What we need is an Andrew Jackson to stand, as Jackson stood, against the encroachments of organized wealth.

We say in our platform that we believe that the right to coin and issue money is a function of government. We believe it. We believe that it is a part of sovereignty, and can no more with safety be delegated to private individuals than we could afford to delegate to private individuals the power to make penal statutes or levy taxes.

Those who are opposed to this proposition tell us that the issue of paper money is a function of the bank, and that the Government ought to go out of the banking business. I stand with Jefferson rather than with them, and tell them, as he did, that the issue of money is a function of government, and that the banks ought to go out of the governing business.

In this regard Bryan was absolutely correct, and as our subsequent history would prove. But of course, one of the final acts of his political career was to assist with the passing of the Federal Reserve Act, which Chesterton informed us that Bryan later regretted. So even the politician is burned when he betrays his best principles. Now Piper comments:

Bryan emphasized the fact that money was the overriding issue of that particular time, given the fractures that had developed within American society. Until that issue was addressed, no other issue was as important:

If they ask us why we do not embody in our platform all the things that we believe in, we reply that when we have restored the money of the Constitution all other necessary reforms will be possible; but that until this is done there is no other reform that can be accomplished.

We would certainly agree, that as long as Jews print our money, we shall never have any sort of political solution to our woes. Piper continues:

Bryan described the conflict over money as a historical and universal struggle and one that was central to a nation's sovereignty:

No private character, however pure, no personal popularity, however great, can protect from the avenging wrath of an indignant people a man who will declare that he is in favor of fastening the gold standard upon this country, or who is willing to surrender the right of self-government and place the legislative control of our affairs in the hands of foreign potentates and powers.

We can tell them that they will search the pages of history in vain to find a single instance where the common people of any land have ever declared themselves in favor of the gold standard. They can find where the holders of fixed investments have declared for a gold standard, but not where the masses have. Upon which side will the Democratic party fight: upon the side of the “idle holders of idle capital” or upon the side of “the struggling masses”?

Fixing a nation’s currency to a gold standard which relies on overseas markets certainly does endanger the stability of the nation since the currency value can be manipulated from those foreign markets. Interestingly, 30 years later in Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler wold make a very similar distinction in regards to the economy of Germany and the parasitic usurers who controlled capital and the currency in the very same manner, and he put them out of business in that nation in 1933. Piper continues and says:

At this point in his fiery speech, the great orator had worked the Democratic convention into a fever pitch:

You come to us and tell us that the great cities are in favor of the gold standard; we reply that the great cities rest upon our broad and fertile prairies. Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic, but destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.

Bryan then laid down the gauntlet to the gold forces and the international financial interests. His words were a populist reaffirmation of the spirit of the Declaration of Independence:

This nation is able to legislate for its own people on every question, without waiting for the aid or consent of any other nation on earth. It is the issue of 1776 over again. Our ancestors had the courage to declare their political independence of every other nation; shall we, their descendants declare that we are less independent than our forefathers? No, my friends, that will never be the verdict of our people.

Therefore, we care not upon what lines the battle is fought. If they say bimetallism is good, but that we cannot have it until other nations help us, we reply that, instead of having a gold standard because England has, we will restore bimetallism, and then let England have bimetallism because the United States has it.

Bryan then concluded his address in words that are among the most memorable ever delivered in a political oration:

If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we will fight them to the uttermost. Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the laboring interests, and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” [William Jennings Bryan. The First Battle. (Chicago: W. B. Conkey, Company, 1896), pp. 199-206.]

Bryan then touched his temples and spread his arms wide – as a man crucified.

“The force of Bryan's last words electrified his audience first into stunned silence, then into an ecstatic rapture that was deafening and chilling,” wrote Sautter and Burke. “This young man from Nebraska was the answer to their most earnest prayers, a leader who could unite all the silver forces.

“The floor broke into pandemonium as bands played, delegates marched, men cried and the foot stomping spread like an earthquake through the immense hall… Chicago poet Edgar Lee Masters, who was in the crowd, remembered, ‘They lifted this orator upon their shoulders and carried him as if he were a god.’”

In his campaign memoirs Bryan was quite modest, giving no indication the affect his words had on the crowd. He commented on the response to his address by noting that “The concluding sentence of my speech was criticized both favorably and unfavorably.” [Ibid., p. 206.]

Bryan thus became the party's front-runner. Congressman Richard Bland of Missouri – popularly known as “Silver Dick’ – had been the favorite up to this point. But compared to the flamboyant orator Bryan, Bland had the misfortune of living up to his name. On the fifth ballot, Bryan prevailed. Arthur Sewall, a wealthy Maine shipbuilder, was named as Bryan's running mate. The party concluded that the presence of an Eastern businessman on the ticket would help allay fears that Bryan was somehow “anti-business.”

The Democratic platform hammered out by Bryan and his followers sent a clear message to Wall Street and the allied Rothschild banking and financial interests in London and the capitals of Europe. The words were defiant – and nationalist to the core:

We are unalterably opposed to monometallism which has locked fast the prosperity of an industrial people in the paralysis of hard times. Gold monometallism is a British policy, and its adoption has brought other nations into financial servitude to London. It is not only un-American, but anti-American, and it can be fastened on the United States only by the stifling of that spirit and love of liberty which proclaimed our political independence in 1776 and won it in the war of the Revolution.

We demand the free and unlimited coinage of both silver and gold at the present legal ratio of 15 to 1 without waiting for the aid or consent of any other nation. We demand that the standard silver dollar shall be a full legal tender, equally with gold, for all debts, public and private, and we favor such legislation as will prevent for the future the demonetization of any kind of legal-tender money by private contract. [Ibid., p. 408.]

On foreign policy the platform was equally forthright:

The Monroe Doctrine, as originally declared, and as interpreted by succeeding Presidents, is a permanent part of the foreign policy of the United States and must at all times be maintained… [Ibid., p. 409.]

While today's Democratic Party wallows in its vast federal power to rework Society in its own warped image, the Democrats of 1896 took a far different view:

We denounce arbitrary interference by Federal authorities in local affairs as a violation of the Constitution of the United States and a crime against free institutions, and we especially object to government by injunction as a new and highly dangerous form of oppression by which Federal judges, in contempt of the laws of the States and rights of citizens, become at once legislators, judges, executioners… [Ibid., p. 408.]

And although the Democratic Party of 1896 was known (in contrast to the GOP and its “McKinley tariff”) as the low-tariff party, the Democrats set forth a measure of protectionism for American workers in their platform that would shock modern-day members of the Democratic “mainstream” who favor untrammeled immigration: “We hold,” declared the 1896 Democrats, “that the most efficient way of protecting American labor is to prevent the import of foreign pauper labor to compete with it in the home market…” [Ibid., p. 408.]

Of course, it is Republicans and their big-business constituents who have always favored unbridled immigration for the sake of cheap labor and expanding markets. It is odd, that today’s Democrats share in that policy, although for different reasons. Odd, or more likely, purposely contrived. Piper continues:

Disgruntled “Gold Democrats” left the Bryan convention in Chicago and nominated one of their own, Sen. John M. Palmer of Illinois, as a protest candidate. The so-called Silver Republicans ditched the Grand Old Party and endorsed Bryan.

The Populist Party, which had made its national debut in the 1892 presidential election, saw the handwriting on the wall: Bryan, the Democrat, had co-opted their major issue. The Populists gave Bryan their nod, but rejected Sewall. Instead, the Populists nominated Thomas E. Watson of Georgia for vice president.

From this point, the Populist Party actually became merged with the Democratic Party, and it disappeared. Again Piper continues:

In reaction to Bryan's nomination, the plutocratic interests allied as never before. The railroads reduced rates so people could travel to see McKinley, who was running a front-porch campaign from his home in Canton, Ohio. Many industrial workers were told by their employers that a shift to silver would shut down the plants and that if Bryan won they should not bother coming to work the day after the election.

As we had said, Jacob Schiff was buying up the railroads, and now we know whose candidate McKinley was. Piper continues:

The 1896 presidential election was historic in that it marked the first time that the plutocrat-controlled media in America made a coordinated national effort to smear a populist candidate – a phenomenon common in the United States today.

According to Ferdinand Lundberg: “The first of these great unified press campaigns to manifest centralized motivation and direction took place in 1896, when virtually every important newspaper, Democratic as well as Republican, plumped for William McKinley and the gold standard, against William Jennings Bryan and free silver.” [Ferdinand Lundberg. America's Sixty Families. (New York: Citadel Press, 1960), p. 287. ]

Even Wikipedia admits that Bryan was opposed by every major Democratic newspaper. Continuing with Piper:

Historian Carroll Quigley succinctly summarized the course of the 1896 election: “Though the forces of high finance and of big business were in a state of near panic, by a mighty effort involving large-scale spending they were successful in electing McKinley.

“The inability of plutocracy to control the Democratic Party as it had demonstrated it could control the Republican Party made it advisable for them to adopt a one-party outlook on political affairs, although they continued to contribute to some extent to both parties and did not cease their efforts to control both.” [Quigley, Ibid.]

Election Day saw a narrow victory for McKinley, who won 51.01 percent of the vote and carried 23 states with a total of 271 electoral votes. Bryan won 46.73 percent of the vote, with 24 states in his comer and a total of 176 electoral votes. The Prohibition Party's candidate, Joshua Levering, and the National Democratic candidate, John M. Palmer – “the Gold Democrat” – each won slightly less than one percent of the vote.

Shortly after the election Bryan assembled a memoir of the 1896 campaign and titled it The First Battle. Thus he implied that future battles lay ahead. Four years later, in the 1900 presidential election, there was a Bryan-McKinley rematch; McKinley's percentage of the vote actually increased slightly while Bryan's declined.

A detailed study of the economy in the intervening years from this perspective may prove telling. The depression ended in 1897. Of course, for the bankers to ensure their grip on the economy of the nation, the economy would have to improve, or they did indeed risk a Bryan victory in 1900. That is exactly what the bankers made happen: the economy improved, so Bryan was less likely to succeed. Piper continues:

Beginning in 1901 Bryan began publishing a populist newspaper called The Commoner, using it as his personal political platform. He continued speaking around the country and keeping his hand in Democratic politics.

Having twice lost the presidency (and control of the Democratic Party) Bryan was unable to capture the party's nomination in 1904. However, Vice President Theodore Roosevelt assumed the White House in 1901, upon the assassination of William McKinley. “TR” emerged as a remarkably popular president, evidenced by the 56 percent of the vote Roosevelt received against Alton B. Parker, his Democratic challenger in 1904. (McKinley's Vice President – Garrett Hobart – had died in 1899 and Roosevelt had been placed on the Republican ticket in 1900.)

McKinley was assassinated by the supposedly Polish anarchist, Leon Czolgosz. However Czolgosz was heavily influenced by the Jewess Emma Goldman, and Goldman was even suspected of and arrested for complicity in the crime. She was released for a lack of evidence. Hobart, a very popular New Jersey lawyer who was expected to run in 1900, suffered a chronic heart ailment which evidently killed him after a deteriorating illness at age 55. The chain of events paved the way for Roosevelt, one of the country’s quintessential imperialists, to become president. Continuing with Piper:

In 1908 Bryan wanted to seek the presidency again, but he was willing to step aside if another candidate would carry his populist message in the campaign. However, no major candidate emerged, and Bryan was nominated a third time; once again falling short. Theodore Roosevelt's hand-picked Republican successor, William Howard Taft, won 51.58 percent of the vote to Bryan's 43.05 percent. (The Socialist Party candidate, Eugene Debs, won nearly 3 percent of the vote and Eugene W. Chafin, the Prohibition Party candidate, won nearly 2 percent of the vote.)

In 1912 there were other candidates in the wings. Bryan's star was fading but House Speaker James Beauchamp "Champ" Clark of Missouri – a populist in the Bryan mold – was gaining strength with support from the Bryan wing of the party.

The other major contender was Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey, the former president of Princeton University. He was a dyed-in-the-wool internationalist with a Anglophilic predilection common to the plutocratic-academic elite of the day.

“Champ” Clark led on the first ballot at the 1912 Baltimore convention, and Bryan was initially inclined toward Clark's candidacy. However, the plutocratic interests knew that a Bryan-Clark alliance stood in the way of their complete control of the Democratic Party. As a consequence they concocted a clever ruse to mislead Bryan and undermine Clark's candidacy.

Through their agents in the press they “leaked” word that the big money interests were lining up behind “Champ” Clark. Also, Clark refused to eschew the support of New York's powerful and popular Tammany Hall boss, Charles F. Murphy. This prompted Bryan into a vigorous attack on Clark, forcing a stalemate. In the meantime the big money henchmen began making deals on Wilson's behalf. The convention dragged on through 46 ballots, ending in Woodrow Wilson's nomination. Ironically, by stalling Champ Clark's drive to the nomination, Bryan shared indirect responsibility for eventual U.S. entry into World War I.

We can only wonder why, after all of his experience, Bryan still believed the newspapers at all. Continuing with Piper:

After winning the presidency Woodrow Wilson appointed Bryan secretary of state. But Bryan was frankly out of place in the new administration, one filled with Old School Tie sophisticates more at home on a White Star or Cunard Liner than a train traveling through America's heartland.

Ironically, it was Bryan who – once again unwittingly – played a major role in a measure that advanced the power of the plutocratic interests he had long battled: the creation of the Federal Reserve System.

Although the story of the creation of the Federal Reserve and much of the subterfuge related thereto is beyond the scope of this article, suffice it to say that it was Bryan's endorsement of the Federal Reserve Act, approved by Congress in December of 1913, that made passage possible.

Although the measure was being steered through by the Wilson administration, it was Bryan’s blessing that led many congressional populists to support the measure. They (like Bryan) had been hoodwinked into believing that it would stem the influence of international bankers over the American economy.

According to William Greider, a historian friendly to the Federal Reserve: “With a few cosmetic changes, the president persuaded Bryan to endorse the measure as a triumph over the ‘money trust.’” [William Greider, Secrets of the Temple, (New York: Touchstone Books, 1987), p. 278.]

Although, according to Greider, bankers publicly proclaimed their opposition to the legislation, “many bankers were also writing their senators urging them to vote for it.” [Ibid., p. 179.] The late Dr. Martin A. Larson, a populist historian critical of the Federal Reserve, pointed out that Edward M. House noted in his own papers “it would appear [that Bryan] never entirely understood” the meaning of the legislation that created the privately-owned banking monopoly. [Martin A. Larson, The Federal Reserve and Our Manipulated Dollar, (Old Greenwich, Connecticut: Devin-Adair, 1975), p. 46.]

Bryan himself ultimately repudiated his role in the creation of the Fed. “That is the one thing in my public career,” said Bryan, “that I regret – my work to secure the enactment of the Federal Reserve Law.” [Bryan quoted in article by George Creel in Harper's Weekly, June 26,1915, cited by Eustace Mullins, The Secrets of the Federal Reserve, (Staunton, Virginia: Bankers Research Institute, 1991), p. 30.]

In our last presentation of this series, we quoted A. K. Chesterton as having said “William Jennings Bryan lived long enough to stand aghast at the horrified thought of what his name, in all innocence, had helped to bring into being, but no such shame cast a shadow on the happiness of Warburg and his friends, who now had exclusive power of note issue to the reserve banks, as well as power to fix the discount rate, which meant, of course, power to determine the amount of money in existence. They had conquered America: they were now ready to conquer the world.” Again continuing with Piper:

In our last presentation of this series, we quoted A. K. Chesterton as having said “William Jennings Bryan lived long enough to stand aghast at the horrified thought of what his name, in all innocence, had helped to bring into being, but no such shame cast a shadow on the happiness of Warburg and his friends, who now had exclusive power of note issue to the reserve banks, as well as power to fix the discount rate, which meant, of course, power to determine the amount of money in existence. They had conquered America: they were now ready to conquer the world.” Again continuing with Piper:

In dealing with foreign affairs, Bryan also seemed in over his head. Although officially the nation's foreign policy czar, matters were developing behind the scenes that were completely beyond his control.

As Bryan's politically astute wife later reflected: “While Secretary Bryan was bearing the heavy responsibility of the Department of State, there arose the curious conditions surrounding Mr. E. M. House's unofficial connection with the president and his voyages abroad on affairs of State, which were not communicated to Secretary Bryan… The President was unofficially dealing with foreign governments.” [William Jennings Bryan and Mary Baird Bryan, The Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan (New York: Kennikat Press, 1925) Vol II, pp. 404-405.]

Of course, it would not be Bryan’s fault if Wilson was sabotaging the legitimate operation of his own administration, or allowing it to be sabotaged by House. There should be little doubt that House was a Rothschild agent subjected upon the compliant and morally compromised Wilson by those who put Wilson in power. But we can only conjecture, that if Bryan was really aware of what was transpiring, he may have resigned in protest sooner than he had resigned. Piper continues:

War was brewing in Europe. Although the U.S. was officially neutral, President Wilson – in accord with long-held sympathies toward imperial Britain he had developed as a Princeton under-graduate – was maneuvering to bring America into the war. In fact, according to Anglophile historian Carroll Quigley, the entire Wilson administration, “With the single exception” of Bryan, was committed to U.S. participation in the war on the side of England. [Quigley, p. 249.]

Ferdinand Lundberg writes of Bryan's efforts to keep America out of the war: “Less than two weeks after war began, [Bryan] informed President Wilson that J.P. Morgan and Company had inquired whether there would be any official objection to making a loan to the French government through the Rothschilds.

“Bryan warned the president that ‘money is the worst of all contrabands,’ and that if the loan were permitted, the interests of the powerful persons making it would be enlisted on the side of the borrower, making neutrality difficult, if not impossible.” [Lundberg. p. 136.]

Bryan's warnings fell on deaf ears. Wilson and his inner circle were committed to U.S. intervention in England's war. The sinking of the RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915 (See The Barnes Review, May 1996) gave Wilson yet another excuse to move toward intervention. Bryan realized his efforts to prevent American involvement were fruitless.

Arthur H. Vandenberg, who as a U.S. Senator from Michigan would later be a leader in efforts to prevent U.S. involvement in the second great war in Europe, noted: “Bryan, who had declared that so long as he was secretary, the country would not engage in war, resigned.” [Arthur H. Vandenberg. The Trail of a Tradition. (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1926), p. 364.]

Bryan returned to private life, devoting his efforts to writing and lecturing. He never sought public office again.

In 1925 Bryan became involved in the last great battle of his life, the famous “Monkey Trial.” Long one of the nation's most prominent and fervent Christian fundamentalist foes of the teaching of Darwin's theory of evolution, Bryan was brought in as an assistant prosecutor in the trial of John Scopes, a Tennessee schoolteacher charged with teaching evolution (which was banned in Tennessee schools). Scopes’ defense attorney was famed Chicago attorney Clarence Darrow, who had actually campaigned for Bryan in the 1896 election. Yet, when the two former allies met in courtroom combat, most observers concluded that although Scopes was actually convicted and Darrow lost, Darrow far outshone Bryan and left the Great Commoner appearing narrow-minded and dogmatic. (The trial was immortalized in the Broadway play Inherit the Wind, later made into a classic Hollywood motion picture).

At his home on July 26, 1925, shortly after the conclusion of the Scopes trial, Bryan collapsed and died. The old warrior was exhausted and perhaps disillusioned. But he had given his all in every fight, and was remembered by one Nebraskan as “the brightest and purest advocate of our cause.” [The Editors of American Heritage, The American Heritage Book of the Presidents and Famous Americans, (New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1967), p. 655.]

Necessarily coming to a conclusion based on our Christian Identity world-view: perhaps Yahshua Christ our God is indeed a master of irony, because we are told by our Scriptures that our kingdom would be handed over to the beast, for reason that we have been the whore for the Jew, the whore joined to the beast which represents Mystery Babylon. So one of the preeminent and would-be defenders of Christian middle America was duped into becoming an advocate of the method by which that handing-over occurred, which we reckon happened when the Federal Reserve Act was passed. From that time, the enemies of Christ have controlled the entire political discourse in America. However we should not condemn William Jennings Bryan. Rather we should only understand the inevitable, that Christ alone is Sovereign and that His will shall prevail in spite of the deeds and intentions of men. So we have been in our current political, economic and social quagmire for over a hundred years, we are sinking into the abyss, and some of us have only begun to notice the dilemma as the mire reaches to our throats. How long shall it be before enough of us awaken and repent of the evil?

A note on the author at the end of the article, who would not have like my conclusion:

Michael Collins Piper is a longtime correspondent for The Spotlight, as well as the author of two books, Final Judgment, which details the role of the Mossad in the JFK assassination, and Best Witness, the story of the attempt by the ADL to silence the historical revisionist movement.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.