Topical Discussions: Flat Earth and Four Corners, Philistines, and Fornicators

Topical Discussions: Flat Earth and Four Corners, Philistines, and Fornicators

Footnotes on Christogenea commentaries:

As I write my weekly Biblical commentaries, and especially since they are written each week as I go along, I get little time to self-reflect, or even to edit whatever I had prepared on Thursdays and Fridays in time for a presentation on Friday evening. Therefore I am bound to miss things that should be included, and I have already made several footnotes in comments in my current Genesis commentary. I am not trying to make excuses, but rather, I am only admitting that whatever I do, it can always be improved. While I would like to be the one who improves my work, often I have some help from my friends, for which I can only praise Christ.

An example of one of the things I had missed, I had discussed at length in our last Topical Discussion program in December, which was the fact that the name adam may translate into the phrase “I, blood”. That is certainly something which I wish I had realized just ten or eleven months sooner, when I presented my commentary for Genesis chapter 2, so instead I had added it to that presentation as a sort of footnote in a comment at the bottom of the page. That way if I ever get the time to make my Genesis commentary into a book, it will hopefully be included. I have added comments to some of my commentaries in the past, but both the Revelation and Genesis require the coverage of such a wide breadth of materials, that it is far easier to overlook things. This evening, we have addenda for each of them. In the future, there will very likely be more.

The “four corners of the earth”.

So this evening I shall first offer a brief footnote on the Revelation, where a certain phrase appears that is used, or misused, by the Flat Earth crowd as some sort of scientific statement on the geological shape of the earth. This view is childish, and it is utterly ridiculous, to take such an idiom as “the four corners of the earth” out of an ancient work of literature, and insist that it must be accepted in a completely literal manner.

In Isaiah chapter 40, referring to Yahweh God, we read in part: “22 It is he that sitteth upon the circle of the earth, and the inhabitants thereof are as grasshoppers; that stretcheth out the heavens as a curtain, and spreadeth them out as a tent to dwell in: 23 That bringeth the princes to nothing; he maketh the judges of the earth as vanity.” There, if the earth is a literal circle, then certain people, must be literal grasshoppers, and the heavens are a literal tent. But the subject of our discussion here is found in Revelation chapter 7 where we see another idiom, which has a similar meaning, where we read “1 And after these things I saw four angels standing on the four corners of the earth, holding the four winds of the earth, that the wind should not blow on the earth, nor on the sea, nor on any tree.” Here, if the corners are literal, then the angels must be able literally hold the winds with their hands to prevent it from blowing.

That phrase, “four corners of the earth”, also appears earlier in the prophets, in both Isaiah and Ezekiel. In Isaiah chapter 11: “12 And he shall set up an ensign for the nations, and shall assemble the outcasts of Israel, and gather together the dispersed of Judah from the four corners of the earth.” If the outcasts of Israel and Judah are cast to the four corners of the earth in a literal sense, then that alone is where they should be found. Then, as it is in Ezekiel chapter 7: “2 Also, thou son of man, thus saith the Lord GOD unto the land of Israel; An end, the end is come upon the four corners of the land.” If this is literal, then the earth no longer has any corners, and perhaps it is only a circle.

The word for land in that passage of Ezekiel is the same exact word which appears in the passage of Isaiah which we have cited here as earth, in a phrase which is precisely the same in Hebrew:ארבע כנפות הארץ. The translators of the King James Version and other Bible versions frequently translate the Hebrew word ארץ or erets (# 776) as either earth or as land, which appears more frequently in the King James Version. The difference is absolutely arbitrary, but the reference is rarely, if ever, to the entire planet as a whole. In medieval English, earth is land, and not a reference to the entire planet, or globe, or whatever it is that one may think that we live upon.

In the Bible, the earliest of these uses of the phrase “four corners of the earth”, or perhaps land, is in Isaiah, who had begun to write at least a hundred and forty years before Ezekiel, some time before 743 BC, which is about the time when the Assyrian deportations of Israelites in the northern and eastern portions of the old kingdom had begun. But what if the phrase is even much older than Isaiah, and what if it is found in pagan writings?

In the 3rd millennium BC, the pagan idol Enlil was the chief god of the Sumerians. He was later worshipped as a minor deity by the Akkadians and others in Mesopotamia. According to the translator of Sumerian hymns as they are presented in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, whose name is S.N. Kramer, at least twenty tablets containing portions of an ancient Sumerian hymn titled Hymn to Enlil, the All-Beneficent have been discovered by archaeologists at various sites in Mesopotamia, and the hymn is reconstructed from those. Some of them were discovered at the site of ancient Ur, the city where Abraham is first found in Scripture. So there we read in part: “Enlil, when you marked off holy settlements on earth, You built Nippur as your very own city, The kiur, the mountain, your pure place, whose water is sweet, You founded in the Duranki, in the center of the four corners (of the universe), Its ground, the life of the land, the life of all the lands, Its brickwork of red metal, its foundations of lapis-lazuli, You have reared it up in Sumer like a wild ox, All lands bow the head to it, During its great festivals, the people spend (all) their time in bountifulness.” [1]

In ancient Greek literature, Delphi, where the famous oracle of Apollo existed, was called the ὀμφᾰλός or “navel” because it was thought to be the center of the world. Here it is evident that the ancient Sumerians thought the same of their so-called Duranki, a word which seems to be a compound phrase denoting a bond between heaven and earth. The translator explains in a footnote that the word kiur in Sumerian is “a part of the Ekur complex”. There is another hymn, found in the same collection in Ancient Near Eastern Texts, titled Hymn to the Ekur, or “mountain house”, which is said to have been the name of the temple of Enlil in Nippur. [2] So just like the temple to Apollo at Delphi, the ancient Sumerians esteemed the temple of Enlil to have been the center of the universe, and apparently also the structure which connected heaven and earth, which may be imagined of a temple.

But in this passage we also read that the universe has four corners, not merely the earth, and that the temple of Enlil is the center of the universe, not merely the center of the earth. Where we read “of the universe” in this inscription, it is in parentheses and it is unclear as to whether the translator added it, or derived it from some term which has an idiomatic meaning. However it is apparent to me that the Sumerians had also thought of their universe just as the Greeks had used the word κόσμος, which is to describe their particular world, their society and the manner in which they perceived it to operate in harmony with the elements of creation around them, as well as with the heavens and the gods who dwelt in them. So now, in reference to the Sumerians, another inscription helps to establish the truth of this assertion.

The phrase “four corners of the earth” was also an expression of the ancient kings, beginning with the time of the Sumerians, which is said to have also been used by the later kings of Assyria and Persia. [3] Here I will offer just one example, from an ancient Sumerian king named Shulgi. From ancient documents, Shulgi is said to have been the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur, and he lived at least 80 years, or as many as 144 years, before the time of Abraham. [4]

In a hymn titled The King of the Road: A Self-Laudatory Shulgi Hymn, the king had celebrated a journey which he had made from Ur to Nippur, which was a distance of about a hundred miles, and we read the following in the opening lines: “I, the king, a hero from the (mother's) womb am I, I, Shulgi, a mighty man from (the day) I was born am I, A fierce-eyed lion, born of the ushumgal am I, King of the four corners (of the universe) am I, Herdsman, shepherd of the blackheads am I, The trustworthy, the god of all the lands am I…” [5] Now should we believe that the universe is a square?

In a footnote, the translator explained that the ushumgal was “a dragon-like mythical creature”\ Quite often, the translators of ancient cuneiform tablets leave certain technical terms, or terms which are not entirely or properly understood, without translating them, and only represent the sounds of the words in transliteration. So here we have seen that earlier, with kiur and Duranki.

Likewise, as we had explained in part 19 of our Genesis commentary titled The Appearance of the Sons of Noah the terms “blackheads” or “black-headed people” as they are found in ancient Mesopotamian inscriptions, from Sumer through the period of the Assyrians, only referred to the people as sheep who were ruled over, where kings considered themselves to be their shepherds, who were doing the ruling.

This early king Shulgi, for whom this lengthy hymn was made on account of his having travelled a journey of a hundred miles, wherein he boasted of having built there “big houses”, of having “planted gardens alongside of them”, and of having “established resting-places” so that “the wayfarer who travels the highway at night, might find refuge there like in a well-built city” [6], could not have had a very large “universe”, since he certainly did not rule over any territory outside of his own small “world” of Sumer in Mesopotamia and some of the lands which were immediately adjacent to Mesopotamia.

Where it was said of Shulgi that he was “King of the four corners” it was not making a statement in reference to the shape of the planet, for want of a better term, which we now know as the earth. He was not a king in the far east of Asia, or in North or South America, or even in nearby Europe or even in Egypt. Shulgi could not have been ignorant of the Hittites in Anatolia, or of the Egyptians, but he did not rule over them. He was only the king of the four corners of his own relatively small world, where “four corners” is obviously only an idiom used to describe the extremities of the land with which he was familiar, where he himself had lived and ruled as its king. His kingdom was not even shaped like a square.

In like manner, in an inscription of the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III, who lived at the same time that the prophet Isaiah had begun writing, he is said to have been: “Tiglath-pileser, the legitimate king, king of the world, king of Assyria, king of (all) the four rims (of the earth)…” [7] Tiglath-Pileser ruled over a world several times larger than the world over which Shulgi had ruled, but it was still quite far from being the entire planet. If his world had four rims, perhaps it was a flat automobile.

Here it should be fully evident that these references to the four corners of the earth, or the universe, or the four rims of the earth, are not to be understood literally as some sort of geological statement affirming the shape of the planet. The same is true in the words of the prophet Isaiah, because the people hearing Isaiah would have understood them the same way that the Assyrians who had read Tiglath-Pileser’s pronouncements would have understood him.

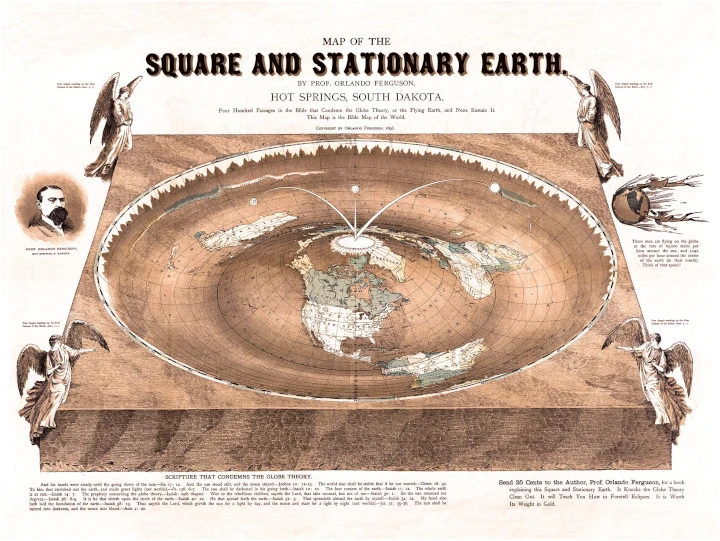

Sometimes these people who believe that the earth is flat will argue with me, claiming that I do not believe the Bible if I do not believe the earth is flat. So I ask them how the earth could be a circle, and have four corners. Then one of them produced a supposed illustration of the earth, which looked like a plastic model made by a toy company and sold as a children’s game or something. It may as well have been made by one of Shulgi’s ancient potters.

A supposed professor made one such illustration in the 1890’s, which we shall include with the written version of this presentation. It is a square with four corners, and inside of it is a bowl-like depression in the shape of a circle, which has a rough sketch of the land masses of the earth sitting in, or atop of its oceans. The sun and moon float around in the sky at the top of the bowl, in a manner which defies time zones and seasons as we experience them – aside from many other physical impossibilities. If the ice melted, the bowl would fill and we would all drown. These people actually accept this model as if it were real, and then they claim that this is what the Bible teaches, so we are not Christians if we do not believe their version of the Word of God. Perhaps in their hearts they mean well, but the truth is that their childish interpretations are not the “Word of God”.

If you are listening this evening, or to this podcast, and if you lean towards this flat earth theory and you are offended by this, you shouldn’t be. You should instead get away from children’s games and toys. I could claim to be even more offended when someone shoves a Hasbro or Mattel toy in front of my face and tells me that it is a model of the earth, and if I do not believe it then I do not believe God. They would assert that the earth sits on literal pillars, but in Job chapter 26 we read that the earth hangs upon nothing, so I could make the same childish claims about them. The earth does not have four literal corners, and even if it did, Ezekiel has informed us that they have come to their literal end. But the reference is only an idiom describing the extent of the breadth of any particular land.

That is my flat earth rant for the first quarter of this year, and now I will move on to more worthwhile and more constructive subjects.

Footnotes on the Four corners of the earth:

1 Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament 3rd edition, James Pritchard, editor, 1969, Harvard University Press, pp. 573-574.

2 ibid., p. 582.

3 Four corners of the world, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_corners_of_the_world, accessed April 5th, 2024.

4 Shulgi, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shulgi, accessed April 5th, 2024.

5 Ancient Near Eastern Texts, pp. 584-585.

6 ibid., p. 585.

7 ibid., pp. 274-275.

The Philistines in the Bible and Archaeology

Now, after speaking to one of our friends earlier this week, I am going to offer another addition to the Genesis commentary, in relation to the Philistim, or Philistines, of Genesis chapter 10. When I did that commentary, I only wrote a couple of paragraphs about them, and mostly in dispute of the idea that Caphtor should be identified with the island of Crete, since ancient inscriptions indicate that wherever Caphtor may have originally been, it was much more likely to have been somewhere the eastern Mediterranean basin. But later in Scripture, and also later in Egyptian inscriptions, it is associated with some place on the eastern Mediterranean coast, or more specifically, on the coast of Palestine, so that at a very early time the label may have moved with the people, but as we shall see, the people were also called by different names at a certain point in Egyptian history.

So here I am going to repeat and expand upon what I had said in that Genesis presentation [and also make some corrections], but I will also elaborate in other ways, because when I had discussed the descendants of Ham in the Genesis commentary, I did not know that certain people who are critical of Scripture or antagonistic towards Christianity mock Scripture and repeat a claim that the Philistines did not exist in Canaan until the 12th century BC, while they are described in Scripture and having been in Canaan in the time of Abraham, in the 19th century BC. Generally I do not read anti-Christ drivel, so sometimes I am not aware of the lies which should be addressed.

This friend in the Christogenea chat had asked: “What is this I'm reading from ‘skeptics’ mocking the Bible by claiming that the Philistines didn't live in Canaan during the time of Abraham, and that the archaeological records only support them arriving among the Peleset sea people there around 1300 BC?”

To this I had answered in part that “What I wrote in Part 15 of my Genesis commentary should be enough to show that the archaeologists really do not understand the inscriptions they translate.” That is often true, but my response should have also explained that those who interpret the archaeologists, if they themselves are ignorant of history, wander even further into error than the archaeologists do. So I will begin by repeating what I had written in my Genesis chapter 10 commentary about the Philistines:

In an article titled New Light on Magan and Meluḫa which was written by W. F. Albright, the noted archaeologist described a cuneiform inscription of 8th century BC Assyrian king Sargon II who referred to the Lubim, Anami and Kaptor in a context which places them beyond the Mediterranean Sea, and Albright states in part that “In a cramped Assyrian hand there is no noticeable difference between [the cuneiform letters which represent] AZAG and ML. It is possible that Anami is the Anamim of Genesis 10, which may represent Cyrene, being followed by Lehabim, the Libyans of Marmarica. The Caphtorim of the next verse are naturally the people of Kaptara, or Crete.” [1] The name Caphtor is said to mean wreath or to refer to something shaped like a wreath, and while Crete does not look like a wreath, it is associated by historians and archaeologists with Caphtor. Marmarica is a name for an ancient area of Greek Libya which was located between Egypt and Cyrene.

Here I will add a note in order to underscore my point of choosing this inscription: Although Albright had identified Caphtor with Crete, he is not necessarily correct, and in the inscription it is evident that parts of Libya, on the coast of Africa, were considered to be “beyond the sea” from the Assyrian perspective, so it is possible that Caphtor as also thought to have been on the coast of what we now know as Africa. Continuing with my citation from the commentary:

Here in Genesis chapter 10 we read that the Philistim, or Philistines, had come from the Casluhim. However in Jeremiah chapter 47 (47:4) we are informed that the Philistines were “the remnant of the country of Caphtor”, and in Amos chapter 9 (9:7) we are once again informed that the Philistines were from Caphtor [or “the remnant of the country of Caphtor”]. Therefore it is evident that the Philistim, or Philistines, had dwelt in the land of Caphtor before their later migration to Palestine, and Caphtor was very probably in Egypt. In an inscription which dates to the 15th century BC titled The Hymn of Victory of Thut-mose III, we read in part: “I have come, that I may cause thee to trample down the western land; Keftiu and Isy are under the awe (of thee)”, and several lines later there is a separate reference to “those who are in the islands”, where Keftiu, or Caphtor, certainly seems to be west of Egypt, but not on an island. [2] However in the historical texts of that same pharaoh, where Keftiu was mentioned along with Byblos in a context which places it on the coast of Phoenicia, we read in a footnote that “Keftiu was Crete – or the eastern Mediterranean coast generally”, and we would agree with that last statement, but only because it seems to associate the Philistines with Caphtor, which was to the west of Egypt but not on an island. [3] Then for that reason mentioned along with Byblos the land which the Philistines occupied in Palestine, which is the eastern Mediterranean coast, was also called Caphtor.

Now I should state that perhaps where that inscription states that Thutmose III trampled the western land and that “Keftiu and Isy are under the awe (of thee)”, it does not even necessarily mean that Keftiu was in the “western lands”. The word Keftiu is the Egyptian word for Caphtor, and just as the archaeologists say that the Philistines had come from Crete, they also claim that Keftiu is Crete, as Albright identified Caphtor with Crete. While I do not know the first archaeologist who made this association, although it may have been Albright, it is simply wrong.

But part of my own confusion has been caused by accepting the statement in Genesis chapter 10 and the other Scriptures where it is mentioned as statementz that the Philistines had actually moved from a place called Caphtor to settle in the lands along the coast where they are found later in Scripture. That is the way that Christian Identity teachers read the passages before me, and also many denominational Christians, even many of the archaeologists of the 19th and 20th centuries, have always understood that interpretation of the passages. But it is simply not true.

From the inscriptions of Thutmose III, it is evident that Keftiu, or Caphtor, was to the north, in Palestine, because that was the route of his earlier conquests as Pharaoh. So in an inscription of the time of this pharaoh, titled Lists of Asiatic Countries Under the Egyptian Empire, we see grouped together in an alphabetical listing: “Kadesh … Karmaim … Keftiu … Khashabu … Kiriath-Anab …” and many other recognizable names, all in a long list of places in or near to Palestine. But the translator added to the entry for Keftiu a reference in parenthesis to “Crete” in quotation marks, as if he himself did not believe it, but perhaps he had to include it in order to satisfy others. The identification is certainly not correct. We read the following in the introduction to that inscription, in part: “The conqueror Thut-mose III initiated the custom of listing the Asiatic and African countries which he had conquered or over which he claimed dominion.”

In those paragraphs from my Genesis commentary I made a statement that I agreed with the latter part of a footnote concerning Keftiu which said “Keftiu was Crete—or the eastern Mediterranean coast generally”, and while I supplied a citation, I did not quote the text to which the note referred. So here it is, from another inscription from the time of Thutmose III, where we read: “Now every port town of his majesty was supplied with every good thing which [his] majesty received [in the country of Dja]hi, with Keftiu, Byblos, and Sektu ships of cedar, loaded with columns and beams, as well as large timbers for the [major wood]working of his majesty.” [4] In that inscription, Keftiu is associated with places on the coast of Palestine where cedar was harvested in trade. From other Egyptian inscriptions, Djahi is in the north of Palestine, in what would later become known as Pheonicia, and Ramses III would later travel by land with horses and chariots to attack the so-called “Sea Peoples” there. Byblos was further north on the coast of Phoenicia, but the location of Sektu is apparently uncertain.

In Jeremiah chapter 47 we read: “4 Because of the day that cometh to spoil all the Philistines, and to cut off from Tyrus and Zidon every helper that remaineth: for the LORD will spoil the Philistines, the remnant of the country of Caphtor.” So the Philistines are the remnant of the country of Caphtor, they are what is left of the people of that country. In Deuteronomy chapter 2, speaking of a much earlier time, we read: “23 And the Avims which dwelt in Hazerim, even unto Azzah, the Caphtorims, which came forth out of Caphtor, destroyed them, and dwelt in their stead.” The meaning of Avims is ruins, and otherwise the people are unknown, so they may have been of the Nephilim, which seems to be the context of that statement. But here we learn that other people, Nephilim or Canaanites, had dwelt in the cities of the Philistines before the Philistines themselves had dwelt in them.

In Genesis we find the Philistines in the south of Palestine, in Gerar. But by the time of Deuteronomy, over two hundred years later, they are in central Palestine, further north, where the later cities of the Philistines are found, and, as we shall see, that is where Ramses III had fought the Peleset, or Philistines. Therefore I would interpret the passage in Deuteronomy to refer to that northward movement, or expansion, of the Philistines which must have happened during the two-hundred years between Jacob’s sojourn in Egypt, and the time of the Exodus. For that same reason, we read in the prophet Amos, in chapter 9: “7 Are ye not as children of the Ethiopians unto me, O children of Israel? saith the LORD. Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt? and the Philistines from Caphtor, and the Syrians from Kir?” So the Israelites came north from Egypt, the Philistines came north from Caphtor, which was much closer to Egypt, and the Aramaeans migrated from some city which is simply called Kir, from a Hebrew word קיר or qiyr (# 7024) which means fortress, and which is ambiguous here.

So it seems plausible that Caphtor was actually in the far south of Palestine near Egypt, which is where the Philistines are found in Genesis, in Gerar which is roughly the land later known as Gaza, and that the people of Caphtor, or Keftiu as the Egyptians had called it, had colonized lands which were further north on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, where they were also associated with that coast near Byblos. So the Egyptian inscriptions seem to be consistent with the Biblical narrative in that regard.

But the claim that there was a “Sea People’s” movement which did not reach the Levant until the 12th century is only an assumption by archaeologists, and it has no foundation in actual ancient documents or inscriptions. This I have recently found in a paper discussing Linear A inscriptions excavated at Tel Haror in Palestine, which is believed to have been the site of ancient Gerar, which was the city of the Philistine king Abimelech in Genesis chapter 26. The site known as Tel Haror is about 16 miles from the Mediterranean coast at Gaza, and about halfway between Beersheba and the coast, which is very consistent with the Genesis account.

This paper to which we refer was written by one Gary Rendsburg of Cornell University, who says in part: “The mention of Philistines in Genesis has elicited much discussion in Biblical scholarship. The usual approach is to consider their presence in these stories as anachronistic.” Here it should be noted that neither Jews nor academic scholars actually believe the Scriptures, even if they make their own livings studying and writing about them. So Rensburg continues: “As it is well known, the Philistines were part of the Seas Peoples movement that did not reach the Levant from the Aegean until c. 1200 B.C.E.” So while Rensburg also offers a few statements refuting this view, he nevertheless seems to accept the myth that Philistines came from some place in or around the Aegean Sea in the 12th century BC, a place which has no history of its own and which has never been conclusively identified. Then he upholds the claim that even the Bible states that they had moved from some other place called Caphtor.

The myth may have been concocted by Jewish archaeologists for Zionist political reasons, since they could then portray any possible descendants of the ancient Philistines as late-comers and invaders in Palestine, rather than as having been there from before the time of the Biblical patriarchs. But of course, the Jews themselves do not belong to the Biblical Patriarchs.

Continuing to answer the initial question, I had explained that simply because the Philistines are not named specifically in Egyptian inscriptions until the time of the New Kingdom empire, does not mean that they did not exist or that they were not found in Palestine. The Egyptians in their earlier inscriptions only referred to "Asiatics" by general names, and while there was some trade, it was mostly conducted through intermediary tribes such as the Ishmaelites and Midianites, and they themselves did not care much for anything in Asia. Evidently, as we had recently described in words from the archaeologist John A. Wilson, in Part 52 of our Genesis commentary, the ancient Egyptians had no imperialistic ambitions outside of Egypt itself until the time of the 17th Dynasty, in the 16th century BC.

The Philistines are mentioned as the Peleset in Egyptian inscriptions from the early 12th century BC and the time of pharaoh Ramses III, in famous inscriptions discovered at a temple place known as Medinet Habu at Thebes in Egypt. Once it is realized that the Hebrew term for Philistine is פלשׁתי or Pelisti the identification is certain. But if critics think that the Medinet Habu inscriptions show that the Philistines only settled in the eastern Mediterranean after the events recorded by Ramses III, that is mere conjecture. In a translation of an inscription of Ramses III titled The War Against the Peoples of the Sea and published in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, a mention is made of the conquests which the so-called Sea Peoples had made in the lands of the Hittites and in Cyprus, and then we read in part: “They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Philistines, Tjeker, Shekelesh, Denye(n), and Weshesh, lands united.” [5] So it appears that the pharaoh Rameses III knew that these tribes had already had their own lands, and it is apparent that he could also identify them. So he attacked them on land before they could attack him by sea.

This is found in another inscription from our same source, titled Summary of the Northern Wars, where we read of the exploits of Rameses III: “I extended all the frontiers of Egypt and overthrew those who had attacked them from their lands. I slew the Denyen in their islands, while the Tjeker and the Philistines were made ashes. The Sherden and the Weshesh of the Sea were made nonexistent, captured all together and brought in captivity to Egypt like the sands of the shore. I settled them in strongholds, bound in my name. Their military classes were as numerous as hundred-thousands. I assigned portions for them all with clothing and provisions from the treasuries and granaries every year. I destroyed the people of Seir among the Bedouin tribes. I razed their tents: their people, their property, and their cattle as well, without number, pinioned and carried away in captivity, as the tribute of Egypt. I gave them to the Ennead of the gods, as slaves for their houses.” The mention of Seir and Bedouins in this context is consistent with the lands of the Philistines and at least some of these other tribes as having already inhabited Gaza and the coasts further north.

A footnote on that same page informs us that the Philistines in these inscriptions were called Peleset by the Egyptians. It is odd that this Egyptian pharaoh of the 13th Dynasty would use a name similar to the one by which the Hebrews had identified the Philistines, because in Hebrew it is said to have had a definite meaning and therefore it may have only a pejorative. The Hebrew word פלשׁתי or Pelisti is similar to a verb which means to roll, and therefore it was interpreted in Strong’s original Concordance to mean rolling, and for that reason, as having described immigrants (#'s 6428-6430). Gesenius was in general agreement with Strong's and added "wanderers" to his definition. [6] But Brown, Driver and Briggs did not make the same conclusion and they themselves do not conclusively define the word. [7] So the word may have been an ethnic appellation, if not a descriptive term, and not a pejorative. They even describe the verb differently, and give an Akkadian cognate which means to burrow or dig or break through something. So there is no real proof that Philistines are immigrants, as Strong and Gesenius asserted, since the definition of the related word does not necessarily mean to roll, and therefore the extrapolation is not necessarily correct.

So what is striking, is the fact that Rameses III had used a term very much like the Hebrew name for the Philistines in order to describe them, which is Peleset, and perhaps it is possible that in his travels through Canaan to attack them, that the Egyptians had learned that term from Hebrews, or through some intermediary contact in Palestine who had also used the term. At this early time, Israel was in the midst of its Judges period, and the state of the nation was pastoral and not well organized, or as centralized as it was in the later times of the Kingdom period. But neither is it certain that Abraham had actually used the term Pelistim, or Philistines, when he encountered the people and king of Gerar some time around 1850 BC, or Isaac when he encountered them about a hundred years later. The accounts are only described in terms which were familiar to Moses and his intended audience, the ancient children of Israel, as he had written the accounts over three hundred years after both Abraham and Isaac had each had dealings with the people of Gerar.

Furthermore, the Genesis account makes no mention of the later cities of the Philistines, most likely because at that time they did not yet exist. So there is no mention of Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, or Gath in Genesis. There is only an association of Gerar with Gaza, in Genesis 10:19, where it states that the border of the Canaanites went as far as far south “as thou comest to Gerar, unto Gaza”. Therefore in that regard, the Scriptures are wholly consistent with archaeology. In the Bible's Patriarchal period, only Gerar is mentioned as a Philistine habitation, and Gerar was in Gaza. There is more than sufficient archaeological evidence for Gerar, which was the home of the people whom Moses had called Philistines in Genesis. So from a website discussing the places mentioned in the Bible, we read the following:

Tel Haror is generally accepted as the site of ancient Gerar, a place mentioned on two occasions in the patriarchal narratives. During the Middle Bronze period (ca 2000 to 1500 BC), Tel Haror was one of the largest cities in southern Canaan, covering 40 acres (16 ha). The tell is surrounded by a rampart of beaten earth and sits on the western bank of the Wadi esh-Sheri’ah, in the valley of Gerar. Located in the western Negev, the site is clearly associated with the Philistine plain but is off the main coastal highway.

They claim here that Gerar was in “southern Canaan”, but the Biblical account informs us that Gerar was south of Canaan, not in southern Canaan, and there is a difference. As for the identification of Tel Haror with ancient Gerar, Gary Rendsburg, in the same paper which we had cited earlier, had written that “Even if Tel Haror is not Gerar, the latter clearly is in the general vicinity of the former.” Speaking of ceramics found at the site, he also explained that their composition is not consistent with their having come from Crete, or with having been local to Palestine. So that and other findings which show that their origin is uncertain is consistent with people who trade, or pillage, by sea. But Rendsburg, after making several conclusions as to the discoveries of Linear A inscriptions and other artifacts found at Gerar, also admitted that “I fully recognize the speculative nature of this conclusion”, while he went on to uphold the myth of a “Sea Peoples wave” into Palestine.

However I would rather believe Ramses III, that the Philistines already had their own lands on the coast of Palestine, and that after he repelled them from invading Egypt, he went north into Palestine and attacked and conquered them. But even before Ramses III, in an inscription of Ramses II from the late 13th century BC, there is a mention of a temple which he had built in Ashkelon. His son Merneptah, who was the first Egyptian ruler to mention Israel in an inscription, had also mentioned Ashkelon. So in a hymn of victory we read: “The princes are prostrate, saying: "Mercy!" Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows. Desolation is for Tehenu; Hatti is pacified; Plundered is the Canaan with every evil; Carried off is Ashkelon; seized upon is Gezer; Yanoam is made as that which does not exist; Israel is laid waste, his seed is not; Hurra is become a widow for Egypt! All lands together, they are pacified; Everyone who was restless, he has been bound by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt: Ba-en-Re Meri-Amon; the Son of Re: Mer-ne-Ptah Hotep-hir-Maat, given life like Re every day.” [8]

From Exodus chapter 13 there is evidence that the inhabitants of Gerar were Philistines, where we read: “17 And it came to pass, when Pharaoh had let the people go, that God led them not through the way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near; for God said, Lest peradventure the people repent when they see war, and they return to Egypt: 18 But God led the people about, through the way of the wilderness of the Red sea: and the children of Israel went up harnessed out of the land of Egypt.”

So all of this serves to help prove the accuracy of the Bible. When the rule of the Egyptians over the Keftiu is first mentioned, it is in the time of Thutmose III in the 15th century BC, and he was actually also the pharaoh of the time of the Exodus from Egypt. Then Philistine cities are first mentioned in the Amarna Letters, where Ashkelon is mentioned, in the time of the later 18th Dynasty. In Amarna Letter No. 287 we read, in part “Let my king know that all the lands are at peace (but that) there is war against me. So let my king take care of his land! Behold the land of Gezer, the land of Ashkelon, and Lachish, they have given them grain, oil, and all their requirements; and let the king (thus) take care of his archers!” [9] Ashkelon is mentioned again in Letter No. 320. [10] The authors of these letters were not Hebrews, and the authors did not call themselves Philistines, or by any other ethnonym.

Then over two centuries later, in the time of a further northern expansion of the Egyptian empire, by Ramses II in the 13th century BC, Ashkelon is mentioned again, but evidently up to this point in history, there is no mention of Philistines by that name in Egypt. In one inscription from his rule we read: “The wretched town which his majesty took when it was wicked, Ashkelon. It says: ‘Happy is he who acts in fidelity to thee, (but) woe (to) him who transgresses thy frontier! Leave over a heritage, so that we may relate thy strength to every ignorant foreign country!’” [11] So Ashkelon is mentioned in Egyptian inscriptions as early as the time of Ramses II who ruled from about 1279 BC, and it is not mentioned in the Hebrew Bible until Judges chapter 14, which began about 390 years after the Exodus! The Exodus having been about 1450 BC, Samson came to judge Israel and battle with the Philistines around 1060 BC. There is an explicit reference in Judges chapter 11 which dates the events of that chapter to about 1150 BC, and Samson came along about 90 years later. So Ashkelon was mentioned in Egyptian inscriptions 200 years before it was ever mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

Likewise, it was not until the time of the 19th Dynasty, and that of Ramses III, that we begin seeing the name Peleset, or Philistines, as an ethnonym in Egyptian inscriptions, which we have already discussed. So before the Hebrew occupation of Palestine, the Egyptians had called the land of the Philistines Keftiu, but later, after the Hebrews had begun their occupation, they called the people Peleset, just as the Hebrews had called them Pelistim. All of this proves that the Bible is completely accurate in regard to the Philistines.

There are many other arguments which can be made. For example, all of the names of Philistines are derived from Akkadian, just as Hebrew, Assyrian, Aramaic and the Canaanite languages were derived from Akkadian. Their god, Dagon, is mentioned on an inscription discovered in Ugarit, far to the north, and dated to the 13th century BC. Dagon was worshipped in Syria as well as in Mesopotamia. The legendary wife of Dagon, Shalash, was worshipped in Ebla and in Mari from the 3rd millenium BC. The same list of Asiatic nations ruled by Ramses III names Beth-Dagon, and a much later Assyrian inscription mentions Beth-Dagon along with Joppa and other cities which were on or near the coast of Palestine. This is all an afterthought, so I will not offer citations, but it is all found in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. The religion of the Philistines, as well as their language, belong to the Levant and not to the Aegean.

Footnotes on the Philistines:

1 New Light on Magan and Meluḫa, W. F. Albright, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1922, Volume 42, pp. 317-322.

2 Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament 3rd edition, James Pritchard, editor, 1969, Harvard University Press, pp. 373-374.

3 ibid., p. 241.

4 ibid., p. 262

5 ibid.

6 Gesenius’ Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament, p. 677.

7 The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon, Hendrickson Publishers, 2021, p. 814.

8 Ancient Near Eastern Texts, pp. 376-378.

9 ibid., p. 488.

10 ibid., p. 490.

11 ibid., p. 256.

On 2 Chronicles 6:24-33

In the context in which the verses concerning strangers in Solomon’s prayer are found, in 2 Chronicles 6:32-33, it is apparent that Solomon had been speaking of Israelites who would potentially be scattered, as he had described in hypothetical circumstances in the verses which precede his mention of strangers. Therefore they would become “outcasts of Israel”, estranged from Israel, rather than citizens of the Kingdom. In this prayer Solomon was not innovating, but rather, there are warnings that these things would befall the children of Israel for their sin in the curses of disobedience in Deuteronomy chapter 28, and prophecies that Israel would be taken into captivity in the writings of Moses.

Verses 24-27: “24 And if thy people Israel be put to the worse before the enemy, because they have sinned against thee; and shall return and confess thy name, and pray and make supplication before thee in this house; 25 Then hear thou from the heavens, and forgive the sin of thy people Israel, and bring them again unto the land which thou gavest to them and to their fathers. 26 When the heaven is shut up, and there is no rain, because they have sinned against thee; yet if they pray toward this place, and confess thy name, and turn from their sin, when thou dost afflict them; 27 Then hear thou from heaven, and forgive the sin of thy servants, and of thy people Israel, when thou hast taught them the good way, wherein they should walk; and send rain upon thy land, which thou hast given unto thy people for an inheritance.”

So Solomon is praying that scattered Israelites might be brought back to the land of their fathers, but historically, we should know that did not always happen. And in fact, there were also many Israelites who had not accompanied Moses in the Exodus, but who had migrated away from Egypt by sea in times up to and including that of the Exodus. Then as he continues, Solomon continues to speak of potentially alienated Israelites:

Verses 28-31: “28 If there be dearth in the land, if there be pestilence, if there be blasting, or mildew, locusts, or caterpillers; if their enemies besiege them in the cities of their land; whatsoever sore or whatsoever sickness there be: 29 Then what prayer or what supplication soever shall be made of any man, or of all thy people Israel, when every one shall know his own sore and his own grief, and shall spread forth his hands in this house: 30 Then hear thou from heaven thy dwelling place, and forgive, and render unto every man according unto all his ways, whose heart thou knowest; (for thou only knowest the hearts of the children of men:) 31 That they may fear thee, to walk in thy ways, so long as they live in the land which thou gavest unto our fathers.”

Then, within this context, where he writes of strangers in the verses which follow, he must be referring to these same Israelites who would potentially become scattered and “outcasts of Israel”, people who may become estranged from Israel and who would no longer be considered to be of the people of Israel in the eyes of men.

Verses 32-33: “32 Moreover concerning the stranger, which is not of thy people Israel, but is come from a far country for thy great name's sake, and thy mighty hand, and thy stretched out arm; if they come and pray in this house; 33 Then hear thou from the heavens, even from thy dwelling place, and do according to all that the stranger calleth to thee for; that all people of the earth may know thy name, and fear thee, as doth thy people Israel, and may know that this house which I have built is called by thy name.”

Within the context of all of the related and surrounding Scriptures, Solomon cannot possibly be asking Yahweh to break his own law and accept people of other races into the congregation of Israel. So it is not righteous to try to force such an interpretation into the mouth of Solomon. Rather, Solomon was certainly aware of the promises to Abraham, that his seed would inherit the earth, and therefore he must be praying that people who had become estranged from Israel would nevertheless seek to return to worship Yahweh, and that they would be accepted. Throughout the verses leading up to the passage concerning “strangers”, Solomon had spoken on the fate which may befall Israelites in various circumstances in their apostasy. When Solomon himself had later wandered into sin and had taken strange wives, these same Scriptures describe his actions as sins, in 1 Kings chapter 11, for example. Therefore he could not possibly have petitioned Yahweh God to accept such sins here, or he would not have had his words accepted.

The Hebrew word נכרי or nokriy does not necessarily refer to people of other races. It merely describes one who is not recognized intimately. While it is often interpreted as stranger or alien, and it may describe such aliens in certain contexts, it is also used of someone of one’s own tribe or race who is simply not recognized. For example, in Genesis chapter 31 Rachel and Leah are described as using this term where they said of their father “15 Are we not counted of him strangers?” In this same manner, Job had lamented in the time of his calamity that “15 They that dwell in mine house, and my maids, count me for a stranger: I am an alien in their sight”, in Job chapter 19. In Psalm 69 David cried that “8 I am become a stranger unto my brethren, and an alien unto my mother's children.” All of these passages used this same term, nokriy. Ruth had also called herself a stranger in that sense in relation to Boaz, using that same word (Ruth 2:10). Rachael and Leah, Job, David and Ruth were not complaining that they were somehow of some other race, or that they had somehow become niggers or chinamen. They were only lamenting that they were estranged from their own families or households. A nokriy is an outsider, someone who is unknown intimately to the beholder, and the term does not designate race or refer to any particular or necessarily different race.

In this same manner, the children of Israel are described as strangers, using a slightly different form of this same term, נכר or nekar, where in a prophecy which addresses the Israelites of the captivity Yahweh promised certain of them a special place if they continue with Him, and describes Himself as “Yahweh God who gathers the outcasts of Israel”, in Isaiah chapter 56. So it is evident in all of these Scriptures that nokriy (# 5237) and nekar (# 5236) refer to someone who is estranged, who was once known but is no longer known, as well as someone who is simply not known intimately.

The root of these two words, נכר or nakar (# 5234), as Strong’s differentiates the spelling of the verb, is “a primitive root; properly to scrutnize, i.e. look intently at; hence (with recognition implied), to acknowledge, be acquainted with, care for, respect, revere, or (with suspicion implied) to disregard, ignore, be strange toward, reject…” etc. So there can be no just insistence that the derivative nouns or adjectives must refer to people of alien races. Rather, in these contexts, they only refer to people not intimately known or recognized, as I have said, although in other contexts of course that would include people of other races.

A few hundred years after Solomon, it was still considered a reproach for racial strangers or even the Adamic people of other nations to enter into the temple of Yahweh, for example in Jeremiah chapter 51: “51 We are confounded, because we have heard reproach: shame hath covered our faces: for strangers are come into the sanctuaries of the Lord's house.” Then also in Lamentations chapter 1: “10 The adversary hath spread out his hand upon all her pleasant things: for she hath seen that the heathen entered into her sanctuary, whom thou didst command that they should not enter into thy congregation.” The word for heathen in that passage is merely nations, referring to people of other, non-Israelite nations. Therefore the law still stood in Jeremiah’s time, and he was lamenting the fact that it was transgressed on account of the sins of Judah.

This same attitude is manifest in Ezekiel chapter 44: “6 And thou shalt say to the rebellious, even to the house of Israel, Thus saith the Lord God; O ye house of Israel, let it suffice you of all your abominations, 7 In that ye have brought into my sanctuary strangers, uncircumcised in heart, and uncircumcised in flesh, to be in my sanctuary, to pollute it, even my house, when ye offer my bread, the fat and the blood, and they have broken my covenant because of all your abominations. 8 And ye have not kept the charge of mine holy things: but ye have set keepers of my charge in my sanctuary for yourselves. 9 Thus saith the Lord God; No stranger, uncircumcised in heart, nor uncircumcised in flesh, l,shall enter into my sanctuary, of any stranger that is among the children of Israel.”

The uncircumcised who had entered the temple at the destruction of Jerusalem were primarily the Chaldees, who were of the Genesis 10 tribe of Aram, and the Scriptures recognize them as a people kindred to the Hebrews who should not be despised, but later in history they made themselves enemies to Israel. So in that context, which is also apparent in many other Scriptures immediately subsequent to the time of Solomon, any interpretation of Solomon’s words as they are recorded in 2 Chronicles chapter 6 which insists that Yahweh would accept aliens, is contradicted in the words of the prophets. But since the Scriptures cannot fail, such an interpretation must be wrong, and the contextual interpretation which we have just offered must be correct. In 2 Chronicles 6:32-33 Solomon must have been speaking of people estranged, not of racial strangers.

Furthermore, where Solomon continues his prayer in 2 Chronicles chapter 6, he maintains the context as we describe it here, so we cannot imagine that verses 32-33 are in some context other than verses 24-31 which we have already discussed, or in verses 34-38 which immediately follow:

Verses 34-38: “34 If thy people go out to war against their enemies by the way that thou shalt send them, and they pray unto thee toward this city which thou hast chosen, and the house which I have built for thy name; 35 Then hear thou from the heavens their prayer and their supplication, and maintain their cause. 36 If they sin against thee, (for there is no man which sinneth not,) and thou be angry with them, and deliver them over before their enemies, and they carry them away captives unto a land far off or near; 37 Yet if they bethink themselves in the land whither they are carried captive, and turn and pray unto thee in the land of their captivity, saying, We have sinned, we have done amiss, and have dealt wickedly; 38 If they return to thee with all their heart and with all their soul in the land of their captivity, whither they have carried them captives, and pray toward their land, which thou gavest unto their fathers, and toward the city which thou hast chosen, and toward the house which I have built for thy name.”

Solomon, a wise man, would not flippantly change the context of his words, and therefore the “stranger” of verse 32 is one who had been estranged, not a racial alien, as circumstances by which people are estranged are the subject of the entire passage, from verse 24 through to the end of the chapter. The Bible is for Israel, and no others.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.

Please click here for our mailing list sign-up page.